There were some studies a few years ago that found that people retain more of a text if you make the font harder to read. I actually believe these studies, because many of the most memorable baseball experiences of my life involved situations where following the game was actively difficult.

I’m thinking about Matt Williams’ breakout game in August 1989, which I listened to in the middle of the woods through barely tolerable Walkman radio static. I’m thinking of the Steve Finley game in October 2004, which I watched on a muted, ceiling-mounted television 100 feet away from me because I was stuck working a weekend crime shift at my old newspaper job. I’m thinking even of the last game of the 2016 NLDS, which I “watched” via the updating ESPN News scroll on a cross-country Delta Flight that carried ESPN but not Fox Sports 1. I swear I experienced that game more intensely watching the ninth inning that way—baserunner dots moving slowly around a scorebug in 90-second increments, Cubs runs multiplying for what seemed like a half-hour straight—than I would have watching the actual broadcast.

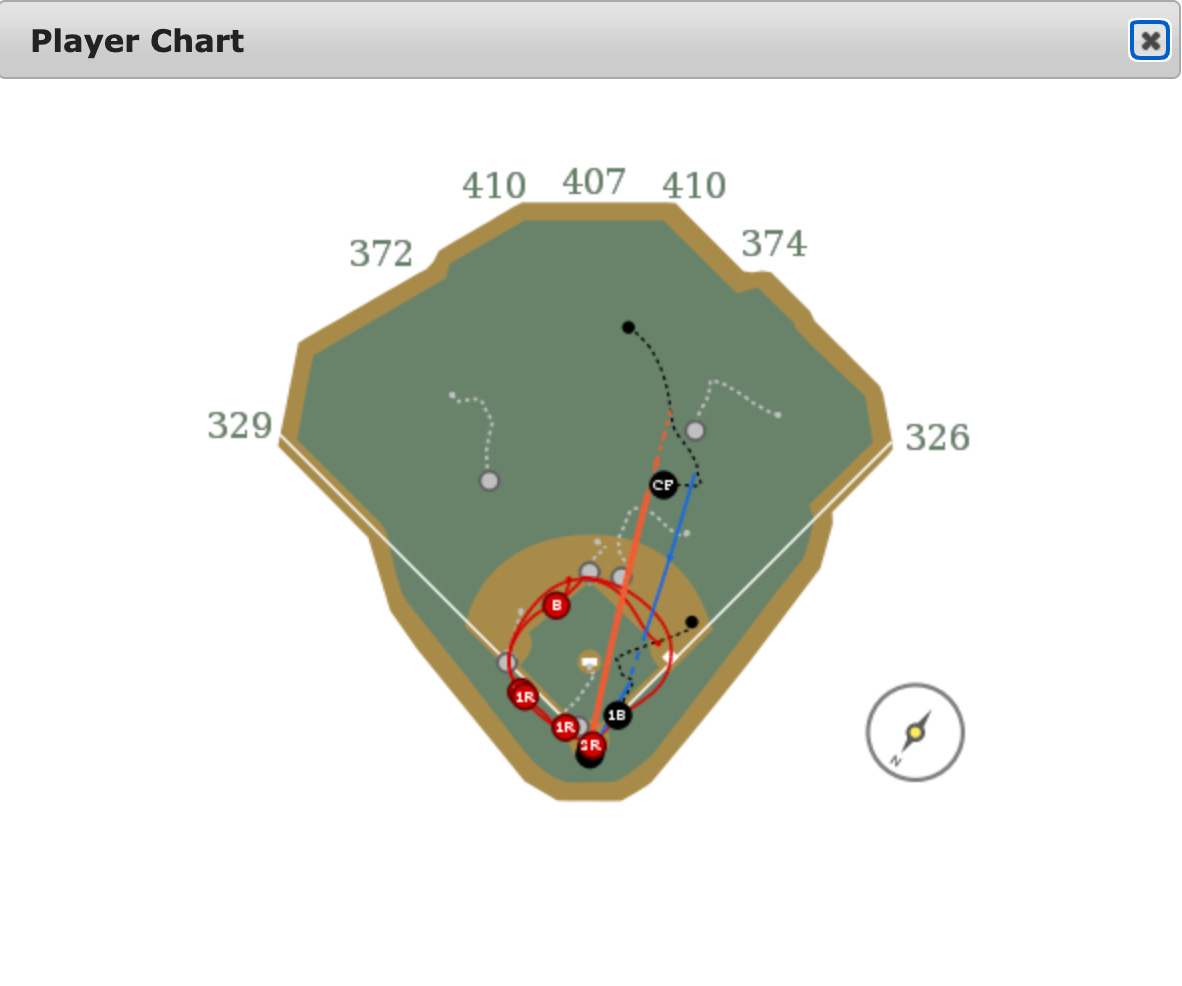

A question I’ve carried around since then is: Can following a game get too hard to still be immersive? I’ve thought about, for instance, what it would be like to follow an entire game by seeing only the left fielder on an isolation camera. Would I know basically who won a game if I just saw a bunch of scenes like this?

As one of the font-studies authors said, “we don’t want to make material so hard to read that people can’t understand it.” The left-fielder experience probably leaves too much out to understand.

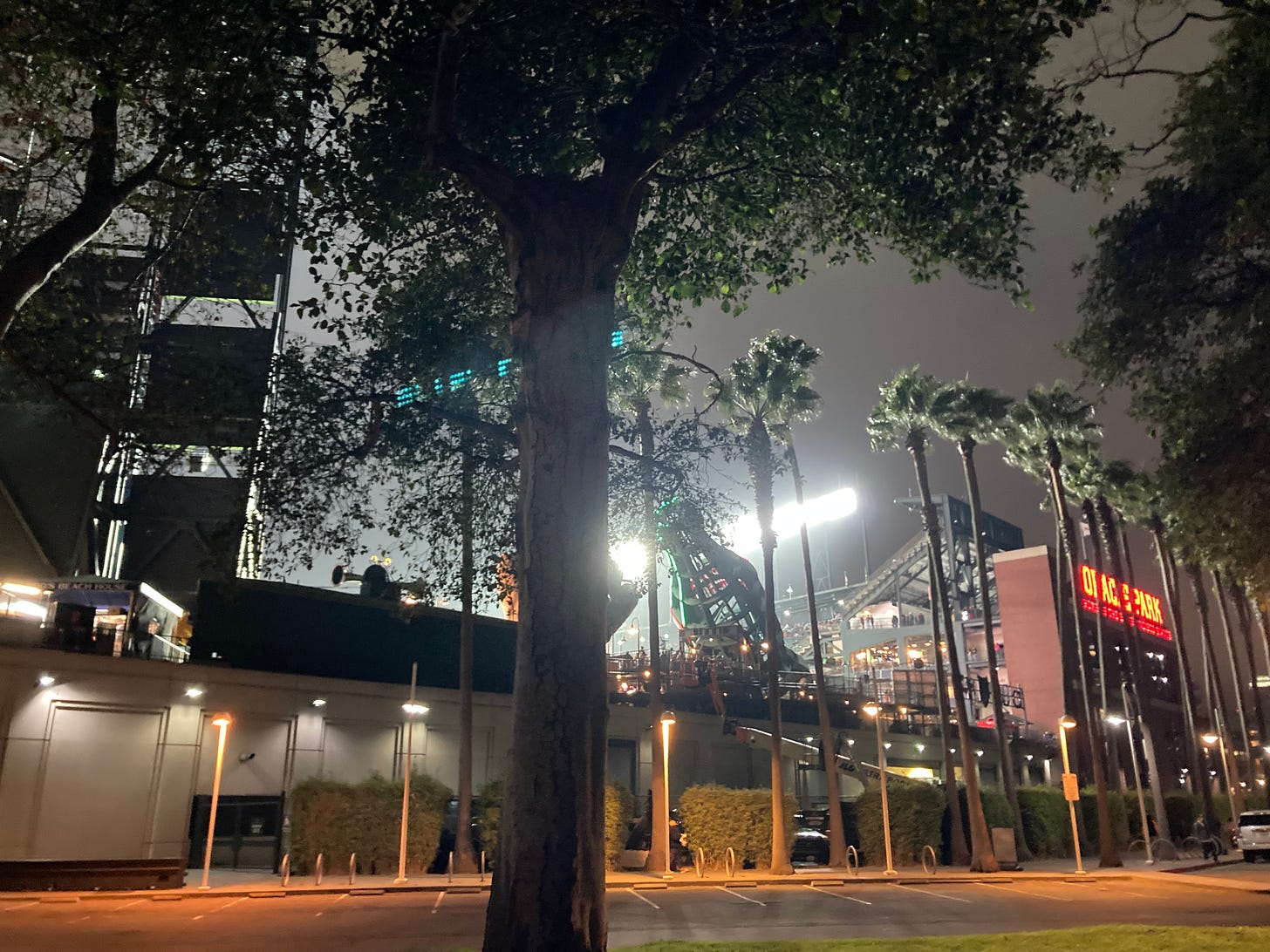

So I decided to try an experience that’s a bit more realistic, that people actually do for fun: I followed a ballgame from the walkways just outside an open ballpark.

**

My best friend Daniel and I went up to the Giants game on Saturday night, Sept. 14. We turned it into a competition, as we have turned literally every interaction we’ve had for the past 28 years into a competition. The rules were: No checking phones, no looking at the scoreboard (which was visible from certain areas outside the stadium) and no peaking at any outward facing televisions. Any other clues from our environment were fair game. The goal was to see who could get closer to describing what had happened.

I had four hypotheses:

1. That 90 percent of baseball can be followed and enjoyed through even the simplest imaginable channel, and that all the other things (broadcasts, broadcasters, replays, graphics, direct lines of sight) are pretty much optional.

2. That, as the game went on, I would become attuned to various auditory hints—and even visual and social clues—that would give me even better understanding of the game’s rhythms. In communing with baseball this way I would come to love it even slightly more.

3. That despite my limited view the game itself would end up being vivid and immersive, and probably even a more emotionally intense experience than if Daniel and I had tickets, or had stayed home and watched it on his couch, both of which we’ve done dozens of times.

4. That I would easily beat Daniel in our competition, because I’m simply better than him, and I always have been.

**

We set up behind the center field scoreboard next to a statue of a seal. Luis Arráez was announced as the first batter of the game. We went silent and I concentrated, expecting to hear the pop of the glove after the first pitch.

Two problems emerged quickly. The first was that we could hear a lot less than I was expecting. Let’s say there are 10 tiers of baseball game sounds:

A donut clinking off a bat in an on-deck circle

An umpire yelling at a dugout that an arguing manager needs to “shut it down”

A pitch, well framed, landing with a satisfying pop in a catcher’s mitt.

A crack of a bat

A crowd’s appreciative hum of approval for a strike call that tilts a count into a home team’s favor

A crowd unhappy about a 6-4-3 double play

A crowd happy about a 6-4-3 double play

Every Body Clap Your Hands Clap Clap Clap Clap Clap Clap Clap Clap Clap

A bases-loaded triple

A walk-off home run

I was hopeful we’d hear Tier 3, optimistic we’d hear Tier 4, certain we’d hear Tier 5. In fact, nothing below Tier 6 was audible outside the stadium, even after we moved next to the lowest point of the stadium’s exterior, with a direct line on some fans.

Sometimes nothing was audible, such as when a party boat floated into McCovey Cove for a half-inning, playing A Bar Song (Tipsy) at the volume of a pre-game-flyover. Generally, though, we could hear everything Tier 6 and up.

But the other problem emerged: In a September game between the out-of-contention home team and the very-much-in-contention same-state rival, a lot of the fans are supporting the visitors. We had a hard time distinguishing tiers 6 and 7, because the crowd’s desires were ambiguous.

Still. Top of the first, not bad:

Let’s go.

**

My Hypothesis 1 was: 90 percent of baseball can get through even the most rudimentary channel. More specifically,

The basic 90 percent: Did something good or something bad happen? If your interest is primarily rooting for a specific outcome, knowing this stuff is arguably enough.

The next 9 percent: The uncertainty or ambiguity that exists briefly and then resolves, e.g. the changing count, e.g. the pitcher trying to hold on the runner, e.g. a ball is in the air and we’re waiting to find out whether it lands fair for a double or foul for a strike. If your interest is primarily feeling the suspense, this stuff is important.

The final 1 percent: Unusual design elements, goofy stuff, never-saw-that-before type things. This is mostly for the sickos.

Sitting outside the stadium, we obviously missed the sickos’ 1 percent, like, say, for instance, a grip of Padres relievers warming up Silly-Walks style:

And we missed most of the suspenseful 9 percent, or at least we misunderstood it. For example, at one point Jurickson Profar was at-bat for a really, really long time. Daniel confidently explained, “The pitcher is nibbling because he’s got runners on second and third.” Daniel had correctly identified that there was suspense happening, a moment that was in flux. But he had the wrong explanation for it. In fact, unbeknownst to us, Profar had obliterated his ankle with a foul ball, and the suspense was whether he would be able to stay in the game.

But as for the last 90 percent—hit or extra base hit or out or multiple outs—I think we passed. On average, we got one-third of plays exactly right (said a double was a double, said a fly out was a fly out). And we were correct on the valence (positive or negative) 82 percent of the time. We couldn’t tell a fly out from a groundout very well, but we could tell a fly out from a double, and that’s enough to get close. We were both rooting for the Giants, and we were both certain the Giants were losing badly.

My Hypothesis 2 was: As the game went on, I would become more aware of the game’s subtle clues about what was happening.

Nope. Maybe if we’d been able to hear Tier 4 and Tier 5 noises, but the level of sound we could access prevented us from really analyzing the progression of plays. We usually only got the one big pop that a play produced, no wax/wane of crowd enthusiasm.

If I learned anything it’s that sometimes baseball events produce nothing audible. Not just no subtle clues, but absolutely nothing.

My Hypothesis 3 was: The game would end up being vivid and immersive and emotionally intense.

Vivid and immersive: Yes, and I don’t think it’s hard to explain why.

Daniel and I basically knew whether good or bad things had happened, but without enough specifics, our imaginations had to fill in the rest. And, almost without fail, we filled in with more narrative, more drama, more excitement than actually existed. To give the most obvious examples: I thought there were three homers and Daniel thought there were four—including a grand slam—while there was actually only one, a solo shot. I thought the final score was 12-2 and he thought it was 10-2. It was 8-0. We knew the Giants had lost but we both exaggerated how many big hits there were, not to mention (in our more detailed notes) how many good plays, close calls, runners out on the bases, and (especially) how many checked swings had been appealed to the umpire. For some reason, we were both convinced that this game was stuffed with half-swings, a rally always riding on a base umpire’s ruling, a crowd distraught over that ruling. In fact, there were no checked swings appealed to the umpire in this game.

So this experience was vivid and immersive because our brains were free to draw it that way!

Emotionally intense? Look, the final score was 12-2 8-0, so I’m not going to say I was living and dying with many pitches after the fifth inning. But there was a moment that will stick with me forever, and that will consequently make this game stick with me forever. It was the eighth inning. The Giants’ Marco Luciano was leading off. There came a big roar! I wrote “double.” Daniel wrote “double.” We found out afterward that it was actually a sliding catch by Fernando Tatís Jr.

I used to go to a ton of Padres/Giants games in San Diego, and it was always like going to a Giants home game. Giants fans would pack the stadium and taunt the Padres fans. We (the Giants fans, circa 2000) had no doubt that we were the superior franchise, and the fact that the Giants could outdraw the Padres in their own stadium was both cause and effect of that. Since then, the Giants have been to four World Series, won three of them, had five MVP winners, poached two Padres managers, while the Padres have been… quietly, sneakily passing the Giants as an organization? Arguably? Maybe not?, but in that moment—when Oracle Park’s crowd let out a HUGE cheer, a joyful eruption, and it turned out that it had been for a nice catch by the visiting team’s right fielder, it seemed undeniable that the power rankings for these two teams had flipped.

Really, from about the sixth inning on—when, the Padres jumped way ahead and when, for record-keeping purposes, I will note that we moved to a third location, beyond left field—all the cheers were for good Padres event. Daniel and I resisted admitting this to ourselves, but the Tatis catch made it clear: The Padres fans had taken over, the Giants were in retreat. For who knows how long—maybe only for a weekend, maybe for a generation, but I won’t forget how that felt.

My Hypothesis 4 was: I would cook Daniel.

I did not. He was closer on both the score and, narrowly, on plays accurately described. He got 28 correct and I got 26. Here are all our guesses and the results, if you’re at all curious.

I’ll just note one last thing: Regardless of the font it’s written in, baseball is more immersive with company. When I told somebody about this experiment, they said something like “wow, Daniel’s a good friend to go with you to do such a stupid, boring thing.” In fact, Daniel’s a good friend because he knew immediately that we wouldn’t be bored at all, that we’d have a great time together, and we did.

I'm a Rockies fan. The fans of the visiting team being louder than the home fans has always been part of the experience, to an extent. But I distinctly remember feeling deflated when I heard the roar of Red Sox fans in Coors Field for the first time. It probably stands out in my mind because I didn't see the actual play. We were running late, so I was on the concourse. I only knew that the Rockies were pitching, the Red Sox were batting, and it was loud after someone got a hit.

I wonder if attending the game blindfolded would produce the desired effect. There’s the issue of safety, and completely shielding yourself from the results of the game on bathroom breaks might be difficult, but you’d definitely be more attuned to the lower tier sounds