Sick Sea Stars Turn Into Puddles Of Goo

A grab bag: Playoff odds, fundamentals, most memorables and analog Saturdays.

I recently learned about the sunflower sea star. Let me tell you quickly about it: It’s about a meter across, so roughly the size of a human child. It’s the world’s second-largest sea star and it lives along the Pacific Coast from Alaska down to Southern California. There’s a virus called sea star wasting disease that makes its limbs fall off and then causes the rest of its body to dissolve into a puddle of goo. In the past decade, this has killed off more than 90 percent of the sunflower sea star population. Ninety percent! Officials have called it “the largest marine wildlife disease outbreak on record.”

How many sunflower sea stars remain? I’m asking you to guess. Without doing any further research, just pick the number that feels right to you. Why am I asking you? Don’t ask why. Party trick. Doesn’t matter. Remember that number.

This is a Reader Engagement Issue. Let’s get into it:

1. The Root Of Fundamentals Is Buttocks

2. The Playoffs Odds Mouse And The Projected Wins Mouse

3. A License Plate I Begrudgingly Admit Is The Most Effective I’ve Ever Seen

4. How To Weed

1. MICHAEL ASKS!

I was watching the World Baseball Classic. John Smoltz says something about how the Japanese team is great at the fundamentals. He was referring to how Sosuke Genda immediately began to square up for a bunt. Sure enough, Genda was able to lay down a successful sacrifice bunt to move the runners over, even with two strikes.

Is bunting actually one of the fundamentals of baseball? Merriam-Webster definition of fundamental: "One of the minimum constituents without which a thing or a system would not be what it is." Does bunting fall under that umbrella for baseball? I don't think so, but maybe.

1) Let's ignore Smoltz and the common way the term is used. Based on the definition above, what are the fundamentals of baseball? What are the minimum requirement to be a baseball player.

2) What are the fundamentals of baseball as it's commonly used? For some reason, Ted Williams stands out as a fundamental hitter to me, and that seems to mean something else entirely. According to Baseball-Reference, he only had five sac bunts in his career.

SM: I'm going to start with.... uh, the fundamentals: What do you think of as the fundamentaliest fundamental in baseball? What's the free-association very first thing you think of? Because I have an answer, and I'm curious if it's anywhere close to your answer. I'm going to put it right down below, after about 10 blank lines, so I don't affect your thinking.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Okay my first snap answer was:

Getting in front of the ball. My snap-adjustment to that snap answer was actually: Using two hands.

Which is interesting, because that's a technique, not an outcome or even a skill. I didn't say the fundamental is "catching the ball." My answer implies that a player who makes five errors while using two hands every time is more fundamentally sound than a player who doesn't use two hands but never makes an error.

MICHAEL: I agree that is a classic fundamental. But I can’t help but think of Bill Buckner, who both got in front of the ball & tried to use two hands.

It feels like his fundamentals failed him in that moment, but he did the two things you’re supposed to do to avoid a careless mistake.

My fundamentalist reaction was: Keeping your eye on the ball. After that it was squaring up the baseball. So the first one is a technique and the second is a result. But it’s not like keeping your eye on the ball necessarily leads to squaring it up. Also, hitting the other way feels fundamental-y but that would be the result of not squaring the ball.

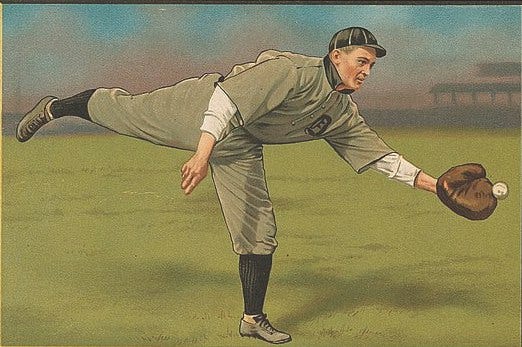

SM: EYE ON THE BALL! That's it. That's the one. Extra points for being fundamental to catching AND hitting, and for being fundamental in pretty much all sports. Indeed, when I looked up “eye on the ball” on Wikimedia Commons, the caption that went with this photo

said: “Steven Miller displayed good form while hitting by keeping his eye on the ball. T-Ball is intended for young children to learn the fundamental skills of baseball.”

A fundament is actually a thing, I'm surprised to learn. Fundamental is the adjective and now we use it as a noun, but the original noun was fundament, which is:

An underlying ground, theory or principle

Buttocks; Anus

Buttocks! Anus! The word fundament comes from the french fundus, for Bottom. So I guess that's how it comes to mean buttocks, too. Let’s all commit to remembering this every time some broadcaster scolds on and on about the fundamentals.

Okay, but back to your questions:

1. Based on the Webster's definition, what are the fundamentals of baseball?

Those are: 1. The ability to hit a baseball with a bat; 2. The ability to tell a ball from a strike; 3. The ability to catch a ball that is in the air or bouncing quickly; 4. The ability to throw a baseball in a direction: for fielders, to a base; for pitchers, in the strike zone. Everything else is mustard.

2. What are the fundamentals of baseball as it's commonly used?

Those are: The ability for batters to do different things depending on the situation--hence Smoltz saying sacrifice bunt, but really what one means by that is the ability to make contact in contact situations, to let it out in let-it-out situations, to aim a grounder to a certain place when needed, to bunt, to shorten up or protect with two strikes, to go the other way if that's where they're pitching ya, to take a pitch when the pitcher’s wild, etc. You could be this type of fundamentally sound player without bunting, so long as you have a general disposition toward flexibility, adaptability, and broad competence.

I'm having a harder time honing in on what it means for fielders, as it's commonly used. I think it mostly means being where you're supposed to be: Backing up where you're supposed to back up, knowing where the play is, positioning yourself in a sensible place, that sort of stuff. Once they’re in the majors, “fundamentals” don’t really apply, so the word is really just a fancyschmantz way of saying “no mental errors.”

There are no pitching fundamentals, as it's commonly used. Throw strikes, move the ball around and change speeds would be most consistent with the way we used fundamentals to describe hitters and fielders. But I just don't think we use that word for pitchers. Before the universal DH we used to use it for the pitcher’s ability to lay down a sacrifice bunt, and now we’re back around full circle.

2. ERIC ASKS!

Do you think there is an overconfidence among knowledgeable baseball fans on playoff odds?

I'd posit that most do not know that variances in simulations do not involve asking "what if this team is better than we think?" but instead ask "how many times out of 162 does a coin that is 55% likely to land on heads do so?" I also think most would be surprised to learn the methodology behind playing time, which are constant in every run of the simulation.

To sum it all up, do playoff odds make you as mad as they make me?

SM: Around this time of year, a baseball fan gets two numbers about their favorite team’s future: One is projected team wins. The other is playoff odds. The choice between them is a deeply, or at least mildly, philosophical one.

Here is how playoff odds are created. I’ll paraphrase FanGraphs’ method, which is basically the same as Baseball Prospectus’ method, just with different proper nouns:

Create a projection for each player based on a weighted average of their plausible futures;

Assign playing time for each player, based on how his team intends to use him and an estimated average of the player’s health outlook

Add it up to get an expected team performance: How many runs they’ll score, how many they’ll allow, based on the players they’re playing.

Using the historical relationship between run differential and record, turn these expected runs scored/runs allowed into an expected winning percentage.

[hold on a minute]

Those first four steps are how we get to the first stage of team projections: The one where a projection system says its best estimate is that the Royals (or whomever) have the talent of a 72-win (or whatever) team and Dayton Moore (or somebody like him) calls it all a bunch of flusterbutter (or what have you). Love all this! I can’t get enough of projections, player projections, depth chart projections, team projections. I’m into this.

Step five is this: You take the team’s expected winning percentage and run just the expected winning percentage through thousands of simulations of the season’s schedule. So when the simulation does its first version of the Giants/Dodgers series in mid-June, it doesn’t start in the first inning, and it doesn’t simulate 90 Julio Urías pitches and a LaMonte Wade, Jr. pinch-hitting appearance in the eighth and the whole deal. That would be… a big ask. No, the simulation is simpler: It might determine that a .510 true-talent team like the Giants will beat a .560 true-talent team like the Dodgers, say, 30 percent of the time, and then it basically runs a random number generator that will give the Giants a 3 in 10 chance in each game; and if the Giants hit that 3 in 10 chance three times in a row they sweep the Dodgers, and if they hit enough of those lucky rolls in the contained universe of that one simulated season they make the playoffs, lose 2-1 in game 5 of the NLDS, etc.

Then it does that several thousand times to create several thousand seasons. What gets expressed as playoff odds is this: In X% of the simulated seasons, the random number generator made the Giants’ expected winning percentage beat the other teams’ expected winning percentage.

At my old jobs, I wrote enthusiastically about these simulated teams that didn’t exist doing amazing things in seasons that hadn’t actually happened. I’d imagine a rich multiverse of infinite Mike Trouts batting infinitely against infinite David Phelpses and find the most slanted universes that the sims had produced. I always wanted to be able to say that, in the simulated season where the Angels won 117 games, Mike Trout had hit [ridiculous stat line] and we’d all laugh at what he could do in the multiverse. I couldn’t, because Mike Trout’s year hadn’t been simulated. Alas. But even more than that, I couldn’t, because that’s not what happened. The Angels didn’t win 117 games in that sim because Mike Trout, or anybody else on the team, had improved, or even had an outlier season, but because the team stayed exactly the same and got lucky in a random number generator.

To be fair, that is a lot of what happens in life. We really are a collection of our best and worst days, and a lot of our best achievements—by whatever measure you might suggest, relational or financial or health or good small talk at cocktail parties—come because the good days, or even minutes, cluster. Many of our mistakes come when the bad weeks, days, minutes cluster.

But that’s obviously not all that happens in life. We are dynamic creatures. We dramatically outperform our “projections” because we get good advice or strong social support or a new sense of confidence, and we underperform because we develop a gluten allergy or somebody invents Twitter. So if you were going to project the entire range of all your outcomes, you wouldn’t come up with one estimated description of who you are and keep running it against the world a billion times. You’d have to build in some huge margin for all the things you might become.

Playoff odds demonstrate, quite convincingly, how much of baseball is just chance. The range of outcomes by chance alone in baseball is huge, and if you don’t believe me, look at one million simulations of a static baseball environment.

What playoff odds don’t do particularly well is capture the full range of outcomes by chance and everything else. They don’t capture, I don’t think, cascading catastrophic injuries, extraordinary coaching and development, extremes of team chemistry, or whatever else causes teams not just to underperform or overperform but actually be radically different.

FanGraphs, helpfully, started publishing the win-total distributions of its simulations a few years ago. If the simulations successfully describe the probable ranges of each season, then half of all teams will end up with a win total between their 25th percentile seasons and their 75th percentile simulated seasons. Thus far, they haven’t. Thus far, they haven’t even gotten close: Excluding the weird 2020 season, 38 teams have fallen within the 25th/75th percentiles, while 82 haven’t. From this I conclude that simulations throttle the true range of outcomes, and that reality is much weirder than chance alone.

That’s not to say playoff odds don’t end up somewhere that’s basically accurate in the aggregate. And they include things like strength of schedule and strength of division, which are useful context. And I think a lot of people prefer to visualize the future in this format, instead of just a projected wins format. Depending on your disposition, it can be a lot more intuitive to hear “they’re 80 percent likely to make the playoffs” than “they have the true talent of an 89-win team.” We all pick our preferences.

Eric, the emailer, has a strong preference. When one site’s playoff odds came out this year, he emailed me: “Worst day of the year.” I don’t feel that strongly, and I’m happy playoff odds also exist. I do have a preference: I prefer to see the future represented by projected wins, before Step 5. I have a tendency to anthropomorphize everything, including projection systems. To me, projected wins are saying “boy, sure is a lot of fluctuation in players’ careers!” And to me, playoff odds, in their final step, are saying people don’t change, they mostly just get lucky. I take that personally!

3. ALEX ASKS!

I saw you tweeted your "The year that..." piece last night [ed. note—this was an article I wrote about the single most memorable thing from every year of baseball], and since it's maybe the piece of yours I think about most often (HM: Robert Gsellman can't swing, and Starling Marte in a world without stats), I'd love to hear what you think we'll remember from the three seasons since you last did this exercise.

I feel like all have been fairly straightforward:

<interrupting this email so that I can answer before reading his answers>

SM: I'm replying to this with my head tilted way down so I don't accidentally see your (Alex’s) picks for 2020-2022. My thoughts are:

2020: Pandemic, obvs. The whole thing, the empty stands, the experimental rules, the teams that got sidelined for like two weeks because of outbreaks in their clubhouses, all of it, but I think if you had to narrow it down specifically to one thing it'd simply be the 60-game stats. You screw up the stats for a season like that and for the next 100 years it will turn up about 50 times a week in a hard-working baseball writer's life.

2021: I honestly think it's the NL West, the race and the division series. That's the greatest pennant race in division-era history, right? There won't ever be another 106-win team that doesn't win the division, right? And it was an escalation of one of the sport's biggest rivalries, and the rivalry that probably gets written about the most? But I *suspect* you (Alex) have written Peak Ohtani.

2022: Judge's 62 homers. It's conceivable that Fernando Tatís Jr. still becomes a top-25 player of all-time, and if so the year he got suspended for PEDs becomes pretty memorable.

Okay sending this before I look, so I can't cheat and edit....

ALEX, continued:

2020 - the year the pandemic broke everything (or whatever)

2021 - the year of Ohtani

2022 - the year Judge hit 62 homers

SM: /rewards self with peanut butter cup.

ALEX: Haha well done! Nailed it.

I should have figured you would go with the Giants/NL West since you were watching every Giants game and no AL at all, but you'll have to take my word that this Ohtani guy had a pretty good year!

SM: Maybe I just don't think 2021 was Peak Ohtani! It was probably his peak as a hitter, and it's probably 50/50 whether he ever wins another MVP award, baseball being what it is. But he's a much better pitcher now than he was in 2021. And this year is well set up to be a more noticeable peak, it being his walk year, it including the WBC, it seeming like a decent year for the Angels to finally make the postseason. And then next year could be a more noticeable peak, too: He gets a new team, presumably a World Series contender, quite possibly a better hitting environment. If he were ever to win the Cy Young and the MVP, or if he were to have a big bold-ink season, or if he were to have a great season PLUS a great postseason, it would probably wash that 2021 season aside a little bit, at least as far as the first thing that 9-year-olds in 2077 learn about him.

ALEX: I think it's possible or likely that he has a year better than 2021 (if he hasn't already) but highly unlikely it ever feels as magical as it did that year, when it still felt so tenuous, as though the slump or the injury would start any day. The longer he goes, the less spectacular any given season feels.

On the other hand I guess also the longer he goes the less any particular season stands out. And you're right, if he one day strikes out 10 in World Series Game 5 and also hits two home runs (or something like that), that would overshadow his breakout.

The problem with Dodgers-Giants is that these days I don't know how many people focus on regular-season division races. What's the last division race anyone remembers? I was about to say maybe the 2011 AL East but then looked it up and realized that was a wild-card race, not a division race. But I won't try any further to invalidate what you experienced as a Giants fan!

SM: And I won’t try to further validate what I experienced, except for this: A few hours after you sent this, I was walking along in a CVS parking lot, peacefully minding my business, when I was ambushed:

In theory, that’s just an extremely niche reference to an early-round playoff game. In practice, I saw that license plate and my limbs immediately fell off and I dissolved into a puddle of goo.

4. MATT ASKS!

Many, many articles ago, you referred to "Saturdays with the internet turned off" as something that you learned to appreciate because someone taught you how. As someone with a real love-hate relationship with technology (I think my constant phone checking is probably my worst trait as a parent), this line really hit me. So I wrote "No internet" in my Google calendar. But when that weekend came, I couldn't do it. This went on for a while—at one point I even had it as a recurring event, but each weekend there was some excuse. Then, one Saturday in the spring of 2020 I actually succeeded, and it was amazing. I started reading my dad's copy of The Brothers Karamazov that he'd lent me six months earlier! I weeded our backyard! I.... probably did some other cool stuff that I no longer remember. At the end of the day I was refreshed. But as great as it was, it didn't stick, the habit didn't form, and I'm back to Saturdays with the internet on. So, long way of saying....how do I do Saturdays with the internet turned off?

SM: I actually don't remember the good advice I got, or the good instructions I got! I've tried to dredge them back up (in my memory or somewhere in an old journal), and I'm coming up empty. But I can give you two small pieces of advice that I feel strongly about, even if I don't know if they're the keys to unlocking this gift in your life.

1. Start the day with a notepad or an index card or something, so that whenever you have a stray thought like “I wonder what Bert Blyleven’s highest Cy Young finish was” or “does eating peanuts cause inflammation” you can write it down to look up later. This was SO important to me. It feels so non-threatening to just make a quick trip to the internet to check the peanuts question. But going to the internet means going to the entire internet, and once you're there you've just opened yourself up to diversions that you're certain you'll avoid but won't. Secondarily, the notecard helped me look forward to the next day, when I could get all my answers. The next day's Big Reveals became like a little reward for me. This was especially true during the season. Sunday morning, get my coffee and read the box scores like I used to do in 1993 to find out literally WHO WON and whether my fantasy guys raked or whatever. So in this way, it didn't feel like I was deprived on Saturday, but that I was imbuing my next internet access with a little spark.

(And a p.s. to this one: If you must look something up, ask somebody near you to look it up for you—or, even better, call somebody who would know. You just want to put some friction between you and your brain's default mode network. And if you do call somebody, boom, you just connected with somebody on the phone, which is always fun!)

2. It 100 percent starts the day before. Or two days before. If you're going to cook something on Saturday, ask yourself on Friday whether you need to print out a recipe. Of if you're going to read a long article that's been open in a tab all week, or email your tax guy, or check the weather. You really want to feel, on Friday night, like what you need exists in the analog world. Really think it through, so that a) you don't have a bunch of excuses to give up and b) you're mentally invested and mentally sturdy for the Saturday experience. If you've done prep for something, you'll be excited to start it. You'll wake up on Saturday excited that the thing you prepped for has arrived.

**

Sea stars. You’ve got your number? I’ve asked this of several people, and they’ve guessed: 17, 200, 3,000, 3,000 and 200,000. The actual answer is:

It’s 600.

Million.

600 Million.

Which means that 10 years ago there were 6 billion giant sunflower sea stars in this world! Spread across a fairly small region of the ocean, some of them just a few miles from me, goo made flesh. There are only 600 million cats in the world, and about that many dogs, and all the while there were 6 billion giant sea stars and I’d never even met one. I just can’t believe how little of this world we’ll ever know, and also that starting tomorrow I’ll know about 200 relief pitchers by their FIPs. Wild.

I'm curious what qualifies for other readers as "The Sam Miller article I think about most often." Mine is Alex's honorable mention of MLB talent evaluation in a world without stats (https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/18683274/in-world-stats-baseball-best-player). I love pitching this concept to people because it's so polarizing, yet the responses I hear basically break down into the four categories Sam outlined.

Honorable mentions:

Imagining a 50 inning baseball game -- https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/21986511/what-happen-baseball-game-went-50-innings

Skunk in the outfield -- https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/20294816/skunk-outfield-how-most-epic-trick-play-history-broke-baseball

Which Shohei Ohtani is the most fun Shohei Ohtani (for a while there, this one grew more fun every year) -- https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/21678789/which-shohei-ohtani-most-fun-shohei-ohtani

There should be a tier where you can pay for a version where Sam reads his work - I basically read it in his voice anyways!