Skenes Should Count

The broken minimum-innings threshold is bumming things out.

Toward the end of September, the Pirates’ broadcast was talking about Paul Skenes’ amazing rookie season, and the dialogue went something like:

Play by play guy: His ERA is the lowest by a Pirate since…

Color guy: Hmm. Doug Drabek?

Play by play guy: Babe Adams. In 1919!

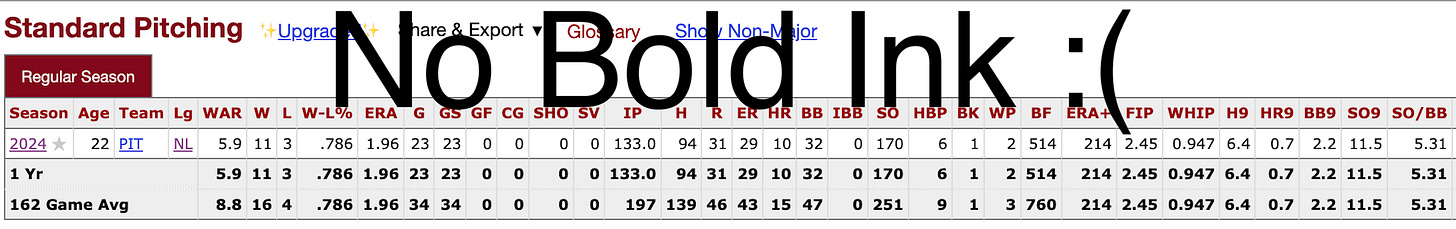

Now, is that true? Unfortunately it’s not, because Paul Skenes’ ERA doesn’t exist. He didn’t throw enough innings to qualify for the ERA title, which requires one inning per scheduled game, or (in normal seasons) 162 innings. Skenes, as a rookie who was kept in the minors until mid-May, threw 133 innings in the majors. He had a lower ERA than the NL ERA champ, a lower WHIP than the NL WHIP champ, and more strikeouts per nine innings than the NL K/9 champ, but he wasn’t eligible for any of those leaderboards, so those are merely fun facts, not anything that counts.

Similarly, he will no longer exist for “lowest ERA by a Pirate since” statements. He won’t exist any more than Red Witt’s 1.61 ERA in 1958 (15 starts, 106 innings) existed when the Pirates broadcasters were talking up Skenes. If, in 10 or 100 years, some Pirate has an ERA of 1.60, the broadcast won’t mention Witt or Skenes. They’ll say that guy has the lowest ERA by a Pirate since Babe Adams. In 1919!

**

That’s only true because somebody who isn’t me has failed to fix it. I first wrote about this in 2016: It’s way, way past time to update the minimum-innings threshold. The current standard—162—doesn’t match how pitchers are used anymore, and it needs to be lower if we’re going to include regular, full-time starters.

In 2016 I took three different routes to get to a better number—at the time, I settled on 130—but I’ll focus on two to show you where we are now:

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were 3.5 qualifying pitchers per team. So a reasonable qualifier would produce about that many qualifiers per team.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a “full-time” starter threw about 250 innings. (Workhorses would throw 300.) The 162 inning threshold, then, captured 65 percent of a “full” season, similar to the threshold for batters (which is 502, out of ~700 for a full-timer, or ~70 percent). A reasonable qualifier for a starting pitcher would be around 65 or 70 percent of what we consider a “full” pitching season, just as it is for a “full” hitting season.

Today, in 2024, we can see where those lines would be set:

To have 3.5 qualifiers per team, there would be 105 qualifying pitchers. In 2024, that would take us down to Bryan Woo, at 121 1/3 innings in 22 starts.

A “full” season today is about 180 innings. (A max season is about 210.) A threshold set at 65 percent of that would be 117 innings (Lance Lynn, 23 starts); a threshold set at 70 percent would be 126 innings (Alec Marsh, 25 starts).

I’d take 120. I’d take 125. I think 130, my figure from 2016, would actually still work well. What we have now (162) doesn’t remotely work:

1970s: ~85 real seasons per year

1980s: ~85 per year

1990s: ~85 per year

2000s: ~85 per year

2010-2014: ~85 per year

2015-2019: ~65 per year

2020-2024: ~45 per year

Half as many qualifying starters, in a league that has 50 percent more teams. Makes no sense.

**

The reason for setting a minimum threshold is to limit the leaderboards, and adjacent statistical relevances, to players who participated in a substantial share of a full season. There’s nothing objectively validating about the number 162; it was just the proper share of the season that kept relievers from infringing on the starting guys’ leaderboards. (And it changed several times.) If “substantial share of a full season” is what we’re measuring, then the rate of players reaching it should be pretty close to constant, and should reflect the changing definition of a full season.

Starters don’t make 40 starts anymore. If everything goes right they make 32, and as Joe Sheehan wrote in his Sheehan Newsletter last month, even that’s not really the norm anymore: “In 2024, even pitching on four days’ rest is unusual. Less than a third of all starts in 2024 were made on four days’ rest. The most common usage for starters now is five days’ rest.” As more teams basically plan on a 6-man rotation—it’s “a fair bet” the Dodgers will in 2025, for instance—even fewer starters will make 32 starts in a season. The Dodgers will have the best rotation in baseball next year and, if they manage a six-man rotation the entire time, they likely won’t have an ERA qualifier.

Not that 32 starts in a season has been enough to get to 162 innings lately. Garrett Crochet made 32 starts this year. He pitched a full season, without interruption, and was one of the best pitchers in baseball. He threw 146 innings. That’s how his team wanted to use him, both to keep him at his best and to avoid destroying his career with an injury. (He led the league in strikeout rate; oh wait, no he didn’t.) Dylan Cease led the league in starts in 2021, and he only qualified for the ERA title by three innings. The way modern teams want to use modern pitchers doesn’t really leave any margin for error, with a very few workhorse exceptions.

Since 2016, a number of great achievements have been lost to irrelevance because the qualifying threshold is too high. Some of them:

Hunter Greene, 150 innings this year, led the National League in WAR but his ERA—2.75, behind only Sale and Wheeler among qualifiers—won’t be on the leaderboard. His season didn’t exist for rate-stat purposes.

Clayton Kershaw, 149 innings in 2016, had what should be considered among the most dominant pitching seasons of all-time—his own best season by rate stats. But he doesn’t get credit for an ERA title that year, or for the lowest WHIP in AL/NL history, or for the highest strikeout-to-walk rate in MLB history.

Chris Sale (158 innings in 2018) would have set the all-time K/9 record, but instead he set nothing.

Carlos Rodon (133 innings) didn’t win the 2021 ERA title, and Tony Gonsolin (130 innings) didn’t win the 2022 ERA title, and Skenes (133 innings) didn’t win this year’s ERA title.

If Skenes had qualified for the ERA title this year, he would have had the best ERA by a rookie in live ball history, and the lowest WHIP by a rookie in live-ball history. (But not the best FIP by a rookie. Spencer Strider, 132 innings in 2022, would have that… but doesn’t.)

Three of the 10 starters who got NL Cy Young votes this year didn’t qualify for the ERA title. Tyler Glasnow got a $30 million/year contract and has never had a qualifying season. Rich Hill has pitched for 13 teams since the last time he had a qualifying season. Eduardo Rodriguez is 28th among active starters in career WAR; he has qualified once. Five teams this year had no starters who qualified—including the World Champions. In 2023, only 11 teams had more than one qualified starter. “Qualified starter” has become practically synonymous with “team ace.” That’s not how it’s supposed to be!

The point of the threshold isn’t to say that there is some magical minimum at which point a pitcher’s performance is impressive. That’s not it at all. (In 2020, a short season, it only took 60 innings to be official!) The point of the threshold is for the leaderboards to accurately reflect who was used in something like a full-time role, by the standards of the league. It’s clear that 130, maybe 140, perhaps 120 innings reflect the league’s standards for a full-time pitcher. Until they make that switch, seasons like Skenes are getting short-changed and I hate it.

I will sign this petition

AMEN. Thank you.