Installment 8: The only pitcher to strike out 10+ batters in each of his first two major league games never did it again.

A little girl once asked her dad if there were sprained ankles in the Garden of Eden. Her father told her he didn’t know. He said origin myths explain things that were supposed to have happened thousands of years before the written word, so we can never really know what “paradise” means, or what we are to make of the vague descriptions of life within it.

But he thought the Garden of Eden describes humans living in a pre-narrative state of nature. Like dogs live. A dog can get hurt, can cry out, can think (on a dog-thought level) “this sucks.” But a dog, living in a narrativeless present, doesn’t have a continual sense of past and future to extend the hurt into. Injury has no deeper symbolic meaning to the dog.

The human, meanwhile, has narrative—a sense that the significance of any moment stretches back to the past and into the future, that there is an overdetermined meaning to things, and that the proper perception of life is through trajectory.

So the Eden myth describes the change in human cognition from instinctive to self-conscious. The human, unlike the dog, thinks, upon spraining an ankle, “this sucks; it’s worse than before; what did I do to make this happen; why did I fail; why isn’t life fair; when will this end; will this ever end; what else will this cost me; am I strong enough to tolerate this; what will happen if I’m not strong enough; will I ever be happy again; how can I control this; why can’t I control this?” This is the toxin produced by the tree of knowledge. It makes pleasure precarious and pain unbearable. Furthermore, because all drama turns on conflict, because all plot is the escalation of conflict, we are trained by our stories to build narratives of concern, worry, peril.

The little girl had by now drifted away, but the father put on a kettle and sunk into these thoughts, which drugged him with melancholy.

He Googled “sprained ankle garden of Eden” to see whether any Old Testament scholars had published commentary on the question. The top result was a health website page: How to Keep a Sprained Ankle from Becoming a Chronic Insecurity.

Exactly.

1. The Beginning

Karl Spooner grew up in milk-farm country in upstate New York. His dad died when he was a pre-teen, and his mom died when he was 17. He walked pigeon-toed and he had flat feet, wore special shoes, and struggled in mud. But his arm was extraordinary. He was known around town for his awesome snowball throwing, and in his adult townball league he struck out 2.7 batters per inning.

Once, he got a tryout start in front of a bird-dog scout, and he arrived just before gametime having bicycled 16 miles, mostly uphill, to get there. George Hodges, the bird-dog, said “Spooner looked less like a pitcher than anyone he had ever seen. That is, he did right up to the point where he let go of the ball. At that juncture, he started looking like Walter Johnson with a tailwind.” The Brooklyn Dodgers signed him and he left high school a year early. His bonus was supposed to be $500, but it was supplemented by an extra $100 to cover his dental bill. At the time, all but seven of his teeth had been pulled.

It took two years for him to find his control as a professional, but in his third minor-league season—in Class A, in 1953—it all started to work. In 1954, he set Texas League records for strikeouts, which inspired comparisons to Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean, who’d set the records Spooner was breaking. In June of that year, he overextended his knee while playing a game of pepper, but as if in a parable the injury turned out to be a blessing. It forced him to ditch his windup and shorten his stride, which he found gave him better control, more stamina and a sharper curveball. He went 12-3 with the bad knee. He struck out 19 batters in one game, 18 in another, and with each great start, the excitement for him in Brooklyn grew. One writer referred to the Drool for Spooner Club. The Brooklyn Eagle, in love, wrote a poem:

He came into baseball all crippled up

Like Mickey Mantle, fleet Yankee bloke.

But he was as game as a bulldog's pup

Althought his flat feet are not a joke.

His toes turn in, but his curve breaks out.

He's a strikeout king on a Dodger farm

Down in Texas where hearts are stout—

Karl Spooner's rich in pitching charm.

He made three fantastic starts in the Texas League playoffs, including one near-heroic loss, in which he pitched into the 17th inning before giving up the game-winning run. He’d thrown about 250 pitches in that game. The Fort Worth chamber of commerce honored him for his outstanding season, presenting him gifts: a sports jacket, two sports shirts, a fishing rod, a reel and net, a dozen golf balls, cuff links and a tie bar set, a billfold, cigars, a dictionary, a bracelet and necklace, portraits, two pair of moccasins, a set of eight glasses, handkerchiefs, luggage, boots and cash.

*************************************************

Meanwhile, in the more famous part of the world, the Dodgers had just been eliminated by the Giants. Their starting pitchers were making up injuries to avoid having to pitch in the final week of the 1954 season, and Dodgers manager Walter Alston was out of patience and options, so he called up Karl Spooner to start the Dodgers’ 151st game of the year. Spooner put on a steel and leather brace to support his knee. Willie Mays was batting fourth.

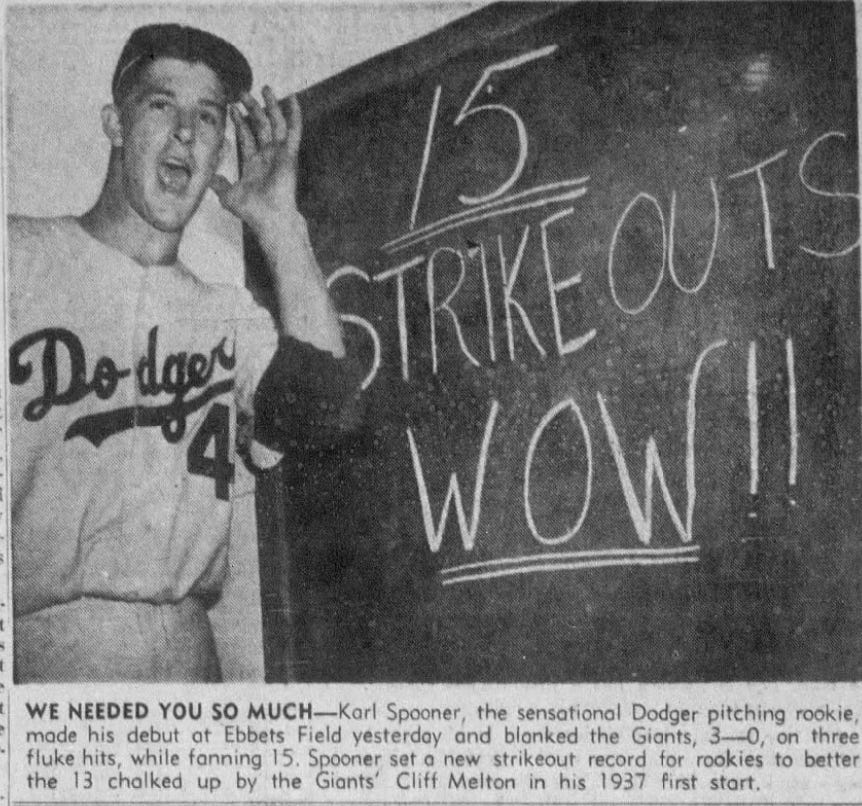

Spooner walked the first Giants batter, then allowed an infield single to Al Dark, and—after retiring Don Mueller and Mays on fly outs—walked a batter to load the bases. But he struck out Bobby Hoffman, and that was basically the ballgame. No other Giant reached second base. Spooner struck out the side in the fifth, seventh and eighth innings. The Giants’ 15 strikeouts were the most by any National League team that season.

It was, to be sure, not New York’s best lineup of the year, especially after Willie Mays left the game for a pinch-runner. But the Giants were the best team in the NL, and even their watered-down lineup was about league average. Spooner faced four batters who got MVP votes. He allowed, in all, only three scratch singles: “A roller toward third on which no play could be made … a pop fly into short right field, and … an even shorter blooper just inside the right-field foul line,” according to the New York Times. It was the greatest debut start in big league history. By a stat that Bill James invented called Game Score, it’s still the second-best debut start, behind only Juan Marichal’s one-hitter. Spooner even walked and doubled.

After the game, Roy Campanella declared him “the best young pitching prospect I’ve seen” and “the fastest boy around.” Campanella reported Willie Mays mumbling to himself, “I never knew this kid could throw this hard.” The veteran Dusty Rhodes, boasting “there isn’t a pitcher alive who can throw a ball past me,” admitted that he had asked for the chance to pinch-hit against him—and struck out on a sweeping inside fastball. An Ed Sullivan producer went to Spooner’s hotel to try to book him for that night’s show. (Spooner and his wife, spying a crowd of fans waiting for him, ducked into the hotel’s back entrance, unwittingly evading the Sullivan slot.) The Orioles’ GM Paul Richards immediately called the Dodgers and tried to trade for him.

The three-graf lede to the Brooklyn Eagle’s game story was a sort of haiku:

The kid grew up in Oriskany Falls, NY.

"That's about 18 miles from Utica."

How far from Cooperstown?

2. The Muddle

Four days later, Spooner faced the Pirates in the final game of the 1954 season. The Pirates were not like the Giants. They stunk. Team president Branch Rickey was tanking the team. Still, they were major leaguers, and every Pirate was better than almost every Texas League hitter. “All right," Pirates manager Fred Haney said before the game. "He struck out 15 Wednesday. He's just as likely to walk 15 today."

The first Pirate of the game reached on an error by Spooner’s third baseman. Spooner then went strikeout-fly out-strikeout, ending the first by putting away All-Star Frank Thomas. Then a six-pitch second inning. Struck out the side in the third. Through eight innings he had struck out 11 batters, allowed only three hits, and protected a 1-0 lead. His manager sent him back out for the ninth. With one out, Dick Cole singled. The next batter, Dick Hall, worked a full count. Cole took off with the pitch; Spooner struck Hall out; Cole was gunned down at second, game over.

So his first start was the greatest in MLB history. His second start was, by Game Score, the fifth-best second start of all-time.

"His fast ball really moves around, which makes it sneaky as well as hard," said Rube Walker, catching in place of Campanella. “But what impresses me most is the way he can take something off a curve ball, still get the pitch over and give it a sharp break. It looks like he can throw a hook at any speed." He also held runners on well—both runners who tried to steal were thrown out—which was observed as a sign of his poise and awareness. Buzzie Bavasi, the Dodgers’ GM, gushed that Spooner was directly responsible for doubling the paid attendance that afternoon.

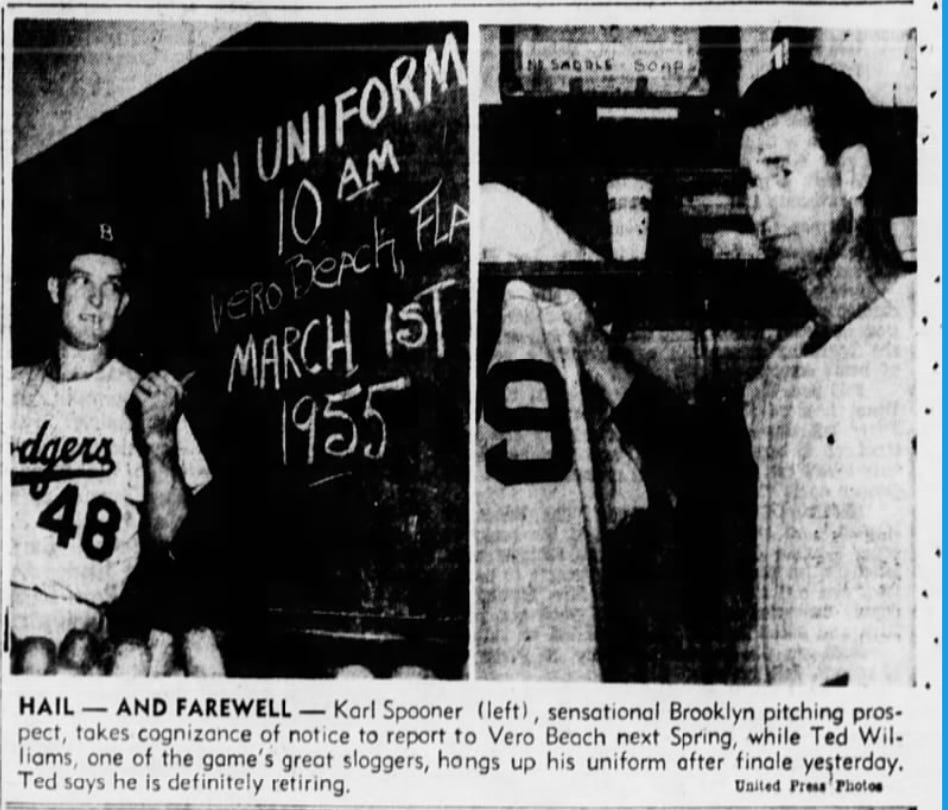

The 1954 season was over. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran of photo of Spooner, still in uniform, hitching a thumb toward a blackboard: IN UNIFORM, 10 AM – Vero Beach, FLA – March 1, 1955. “Wait ‘till next year,” the Eagle promised. A few weeks later, Spooner had surgery to fix the knee he’d injured playing pepper in Texas. A few weeks after that, he impressed everyone in Old Forge, New York—where he was named king of the Winter Carnival—with his famously awesome snowball throwing. A few weeks after that, he arrived to Vero Beach, FLA in uniform by 10 a.m., the hype having grown all winter.

How it went wrong is a bit of a mystery.

Vin Scully said Spooner hurt himself throwing pitches for a publicity photo—his downfall caused directly by his hype, what irony! Walter Alston said Spooner hurt himself playing catch on the sidelines before a game—his downfall caused by the banalities of everyday life, what injustice! Some people said he had thrown too many snowballs that winter in Old Forge, New York. We also know he was worked hard the previous summer, while nursing a bad knee.

But there are two explanations that Spooner himself pushed. Both seem realistic and direct, and they nicely split into two directions: One where Spooner is to blame, and one where the club is to blame. The one he is to blame for is his unilateral decision to throw 30 minutes of batting practice—“against the advice of several old pros”—on March 15, 1955. On March 19, the first reports of pain in the back of his shoulder and trouble cutting loose were published.

But later tellings would put his first pain earlier, before the batting practice, and those would put the blame on Walter Alston. In this story—told in installments months and years after the facts—Spooner was scheduled to pitch the fourth, fifth and sixth innings of an early-spring game against the White Sox, on March 13. But that day’s starter, Johnny Podres, pitched so poorly that Alston abruptly ordered Spooner to get ready to come in for the third. And then the Dodgers went out so quickly that Spooner was suddenly in the game having thrown just 15 or so warm-up pitches.

Spooner: “I got rid of the first hitter, but somebody beat out a swinging bunt down the third base line and then I walked a man. I decided to bear down a little and [Walt Dropo] hit into a double play. I had no trouble in the fourth inning and Ed Roebuck took over in the fifth. Just before leaving the park my arm and shoulder started to throb. I asked Harold Wendler, the trainer, to rub in some oil to keep the arm warm. I told him about the throbbing. He said I had to expect it the first time out. But I felt that this wasn't good. I never had arm trouble before.”

Spooner would pinpoint the exact pitch: “I felt a twinge—I guess you could call it that—when I threw to Walt Dropo. I'll never forget that curve ball. Dropo grounded into a double play. I got out of the inning.” Another later recollection: “On the bus ride back to camp my arm ached like a toothache.”

Some of the details in these stories are wrong: Spooner came in for the sixth inning, not the third; he was the Dodgers’ third pitcher, not second; the date was different than later reports claimed; etc. But many are precise, and accurate: He gave up the swinging bunt to Minnie Miñoso, he got Dropo to hit that double play, he left the game an inning earlier than expected, his arm ached like a toothache on the bus, Doc Wendler told him it wasn’t serious, two days later he threw 30 minutes of batting practice, and over the course of a few days, then weeks, then years, it became kind of clear that the pitch to Dropo was his last really good one.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.