They Boo Shortstops, Don't They?

Finding an identity in somebody finding an identity in somebody finding an identity.

Installment 5: Every time Johnnie LeMaster played on a team last season, it ended up in last place. His teams wound up losing 306 games, which is either a record of some sort or ought to be. –The New York Times, April 7, 1986

1.

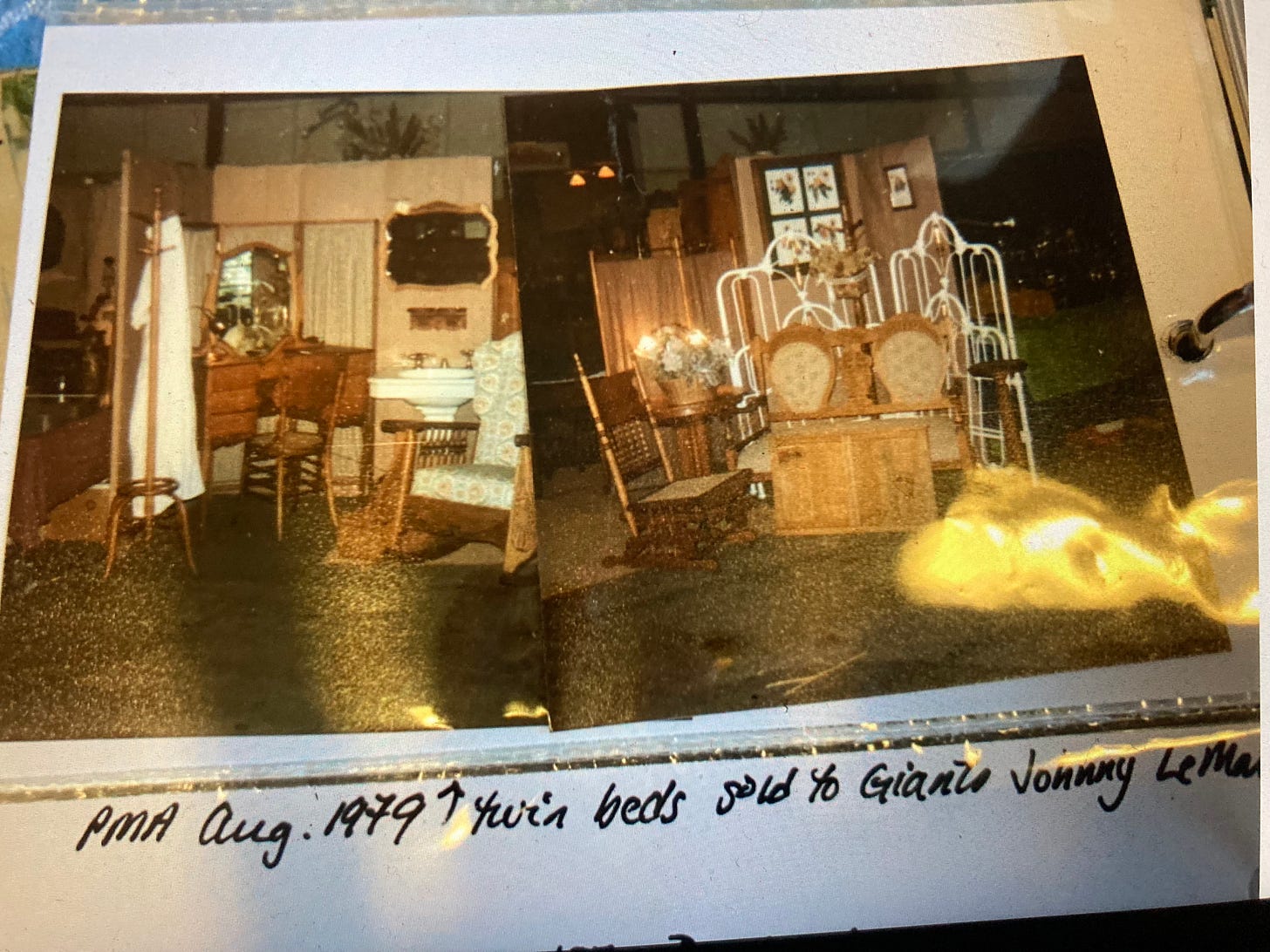

It’s the afternoon of September 2, 1979, at an antiques show in San Mateo, California, and Debbie LeMaster has just stopped to consider two beds. The beds are brass and iron with gallery footboards. They cost $850 for the pair. Debbie asks the woman selling the beds to hold them until she can consult with her husband, who is still at work.

The antique seller asks what Debbie’s husband does that he’s at work on a Sunday afternoon. Debbie says he is a ballplayer, and he is playing in a game right that moment, 15 miles up the San Francisco peninsula at Candlestick Park. Her husband, of course, is Johnnie LeMaster, shortstop for the San Francisco Giants. Debbie is optimistic about the beds: “He’s in a good mood, because he just got a hit.”

That is my mom selling the beds, and that is my dad standing just offscreen, waiting to help load beds into somebody’s truck or van or wagon. Neither Mom nor Dad knows who Johnnie LeMaster is. Mom grew up in a town built to house Manhattan Project engineers, later fled to Berkeley in the 1960s, and considers team sports militaristic. Dad grew up in a competitive family with an athletic dad and an athletic kid brother, and he still carries the irreversible insecurity of having weighed 90 pounds in high school. There isn’t much room in their Venn diagram for the ambitious masculine sociopathy of modern professional sports.

Then Johnnie LeMaster shows up. My family will never be the same. This moment is the origin story of my entire life.

“I was shocked,” Dad told me, when I was grown. “He was smaller than you, smaller than me. He looked like a 17-year-old kid. So I started following him.”

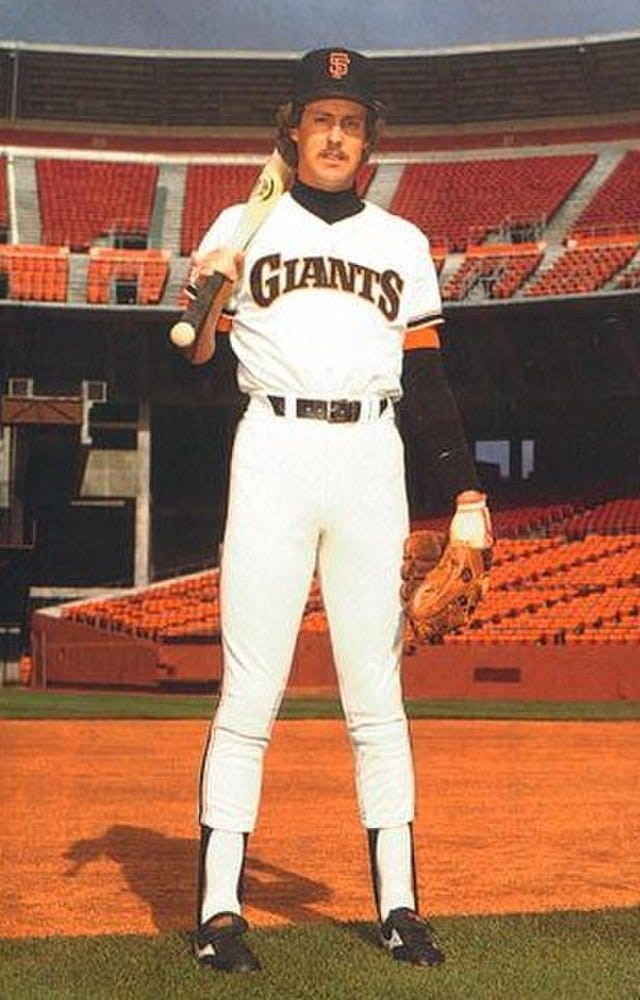

LeMaster wasn’t small so much as slight. He was listed 6-foot-2 but he weighed 160 pounds—the same height as Mike Trout, minus 75 pounds of muscle. His teammates gave him the meanish nickname “Bones,” and the even meaner alternative “Muscles.”

“Basically he was a defensive hitter,” his hitting coach Jim Lefebvre once said. “The pitcher could practically knock the bat out of his hands.” In that 1979 season he was the ninth-worst hitter in the National League, and that was his second-best season as a big leaguer. He had a fantastic arm, was generally considered a sharp defensive player, and he could run a bit. The Giants valued him enough to play him almost every day, rebuff trade requests, and sign him to a multi-year extension. But hitting was hard for him.

That’s what it took for my dad to care about Johnnie LeMaster: He had to know that his job as an elite athlete was difficult, which is not something you necessarily internalize from watching the best athletes in your grade effortlessly dominate every sport while you’re growing up. More importantly, Dad had to know that a hit put Johnnie in a good mood. A hit didn’t go into some big coin jar where Johnnie was saving up for a future sense of having Made It. Johnnie had no savings. Every hit was, to Johnnie LeMaster, a big deal today. It was a surprise, it was sustaining, and it was grace.

What Dad would learn, and what would make him love LeMaster even more, was that all the other fans hated the guy.

Over the rest of that 1979 season, LeMaster batted 85 times and had 20 hits, and those 20 hits, described by Giants’ radio broadcaster Hank Greenwald, meant something to Dad that strangers’ play never had. On antique-buying roadtrips, on afternoons in the workshop, he was becoming hooked on Johnnie LeMaster’s good moods. This Johnnie LeMaster fan became a Giants fan, and he eventually became sustained by the daily rhythm of caring very deeply about pitches described over the radio. He got to loving baseball, and when I was 6 years old, he got to share it. In the past 35 years, I doubt Dad and I have spent a single day together without baseball coming up.

2.

It wasn’t always difficult for Johnnie LeMaster. He was the best athlete Paintsville, Kentucky ever produced, with 21 varsity letters, in football (quarterback), basketball (center, 21 points per game), golf (high-70s) and baseball. Thirty scouts went to his high school baseball games his senior year, when he hit .533 and (as a pitcher) won four games, saved three others and allowed one hit—and no earned runs—all season. The Royals picked ninth in Major League Baseball’s amateur draft his senior year, and if they’d had the chance to take LeMaster they would have made him a pitcher. But the Giants, picking sixth, liked him as a shortstop.

He quickly reached the National League. In his first plate appearance as a big leaguer, he was facing the future Hall of Famer Don Sutton. He swung and missed at two curveballs to fall behind, no balls and two strikes. The Dodgers’ ace then tried to dust him with an inside fastball. LeMaster cracked a line drive into shallow center field. It caught a seam in Candlestick’s artificial turf and bounded over the center fielder’s head, and LeMaster ran out an inside-the-park home run.

But, as you know, Johnnie LeMaster couldn’t actually hit, and over the next three years Giants fans figured it out, too. Then, unexpectedly, they started to boo him.

This was a significant rupture in the normal relationship between fans and players. Fans almost never boo players just for being bad—or, as Reggie Jackson once said, “fans don’t boo nobodies.” Most booing is of opponents—the really good ones, the really mean ones, the time-wasting ones—or of umpires. In the rare cases that fans boo their own players, the booing is usually entangled with how good the player is. When failure is on a team-wide level, for instance, fans sometimes focus their anger on the team’s best player in a kind of synecdoche. (Early-1960s Giants fans, infamously, “cheer Khrushchev and boo Willie Mays.”) And some fans can’t abide anybody making superstar salaries without some accountability for failing to perform constantly as a superstar. But in both cases, one might plausibly argue that the booing is based on a perverted version of respect, not bullying. When bad players are booed, it’s for individual bad plays or bad innings or for demonstrating bad effort. It’s specific and it’s passing. But with LeMaster, fans booed the man, consistently and for being. They didn’t boo when he struck out, but when he came to bat.

It started in 1978, LeMaster’s first season as the Giants’ everyday shortstop. His spring training that year was cursed: He batted better than he ever had, creating unreasonable expectations that he might actually hit as a major leaguer; and he fielded worse than he ever had, planting the fear that he might be unreliable at an exalted defensive position. The hits didn’t carry over to the season, but a handful of the errors did.

On April 18, there were 7,000 Giants fans in a stadium built for 56,000. The Giants had ace John Montefusco on the mound, and he pitched beautifully, but his teammates managed only a single hit. LeMaster made a throwing error that led to a run, and the Giants lost 1-0. The fans booed the goat, LeMaster. And then they just… never stopped. They developed a habit and never bothered to break it.

“Why was LeMaster picked out? For the last three years, you could have booed any Giant at random and been more accurate than singling out the country boy,” one newspaper columnist wrote. But we don’t need our stories to be true, so long as they fulfill something we need, in a narrative we can tolerate. “The Enlightenment world has an innate tendency to degenerate into myth,” the philosopher Justin E.H. Smith said, and a myth becomes more true each time it is called upon. It would be too emotionally draining, too real, for Giants fans to hate all 25 players on their losing club, so they invented a myth that LeMaster alone was the scapegoat, so unprecedentedly bad that he deserved unprecedented retribution. Once he was the guy you booed, no better reason than that was needed. And because they weren’t booing his mistakes, which he might avoid, but his existence, there was no signal for them to stop.

Within a week, “you didn't need a scorecard to know who was coming to bat for the San Francisco Giants,” according to a San Francisco Examiner column. In 1979, they cheered when he was hit by a pitch—not because he reached base, according to the day’s accounts, but because he felt pain. ("They probably wished I'd got hit in the head instead of the arm,” LeMaster glumly conceded.) Fans booed his annual introduction on Opening Day.

It was almost certainly a small share of Giants fans who, in 1978, went to home games predetermined to torment the no. 8 hitter. But a boo, delivered as it is in a different octave than other fan outbursts, has a remarkable ability to be heard. Even 10 fans booing into a headwind of cheers might be noticed enough to be reported in the next day’s game story. These fans’ constant bullying seemed to give the sportswriters permission to do the same, and LeMaster was mocked as no other unremarkable player in the league was. “Johnnie Disaster,” some called him. To be sure, they also wrote lots of sympathetic profiles of LeMaster dealing with the boos, but it’s unlikely these did anything but normalize a new Candlestick Park tradition: Complain about the cold, throw things at the Crazy Crab, root-root-root for the home team, boo Johnnie LeMaster.

3.

“When you’re a ballplayer especially, you want to please your home fans,” LeMaster said, years later. When you’re a ballplayer especially, he says, but really ballplayers are just about the only people in the world who have home fans. The transaction between ballplayer and fan is unlike any other commercial profession. Johnnie LeMaster’s job was simply to let people love him, and he tried, and they spit him out.

LeMaster really, really tried. He tried to get the fans to stop booing, but he also tried to simply ease the torment. Most famously, he attempted to diffuse their hatred with humor, with an idea that came from his wife: On July 23, 1979, for an inning or two, he wore a jersey that had the word “Boo” in place of his name. He popped out to third in his only at-bat in the jersey, then was fined $500.

But LeMaster lived with these boos constantly, and that was just one day’s solution. He spent hours in the bullpen with a sports psychologist to learn to live with boos, he put cotton balls in his ears to try to block out the boos, he drank raw eggs and put on 25 pounds of muscle to try to end the boos. He tried to reason with fans, pointing to his ghastly numbers at home/road splits—the first year of the booing, he hit .299 on the road and .163 at home. “If I play tense, I'm one of the worst players to play the game. When I'm relaxed, I'm one of the best,” he pleaded. That didn’t stop them, either.

He always had a new plan. “This year, when somebody yells ‘Ya bum’ at me, I’m going to smile up at him and say, ‘Hey, thanks a lot. Have a good time at the game. I’m going to deal with it this year and not hide from it like last season.” Or: “I’m going to act like Charley Hustle this season. I’m going to run to first base when I get a walk. I’m going to do some head-first slides. I’m going to show emotion. It’s going to let people know I have confidence in myself.”

He tried to invalidate the booing by framing it as a dehumanizing, big-city phenomenon that existed outside of him—something he could simply reject. He compared the booing San Franciscans with the fans back in Paintsville: “No, I never heard a boo at all back home. You can’t do something like that and get away with it back home. Here, among all these people, you can get away with it real easy.”

But, ultimately, the booing broke him. I count three signs that LeMaster had been truly shattered by the time he left San Francisco.

The first: In 1982, the Giants announced their 25th Anniversary Dream Team, voted on the previous season by fans. LeMaster had been named the shortstop. While this seems odd—he was booed every night!—remember that most fans probably weren’t booing him. To most fans, LeMaster was a familiar name who had been starting for the previous half-decade and who was coming off his best season. Reporters surrounded him: Congratulations, Johnnie LeMaster! This must be a thrill, etc. and so on--

"I honestly couldn't tell you why they picked me," he said. As LeMaster said that, his eyes became fixed momentarily on the locker room wall opposite him. It was as if he was searching for an answer there. He couldn't find one. It befuddled him. "Maybe they felt sorry for me."

He was becoming incapable of feeling others’ love.

The second: Through it almost all, reporters wrote, LeMaster had stayed kind. He did countless interviews—about being booed, but also about everything else—and almost always defended the fans. But by 1982, he cut off the media. Which is fine. He’d actually done that once before, in 1978, when he’d lost his starting job, because he worried he might blurt out his unhappiness and cause a distraction. But in 1982 he didn’t just refuse questions; “when [reporters] got within 10 feet of him, LeMaster would scream insults and invectives at them,” reporters said. Which, again, might be a normal and natural response to struggles, within any of our capacities. But the reporters themselves, who knew LeMaster’s temperament well, saw real tragedy in what the sport’s abuse was doing to him: “The transformation from a genuinely nice person into, at times, an ogre was disturbing to watch. The baseball business is cruel, certainly, but to milk the natural sweetness out of Johnnie Lee was cold-blooded.”

The third: In 1985, when a reporter asked him “when he first wanted to be traded from the San Francisco Giants.” His response: “After my first at-bat in the big leagues.”

And, according to the writer, LeMaster went on to describe that at-bat: He was facing the future Hall of Famer Don Sutton. He swung and missed at two curveballs to fall behind, no balls and two strikes. And then, LeMaster recounted, the Dodgers’ ace… threw him another curveball and struck him out. No fastball inside. No line drive to center field. No seam in the artificial turf and no inside-the-park home run. LeMaster said, in 1985, that Sutton had struck him out and the fans had booed him on his return to the dugout. “As I walked back to the dugout I was thinking, here I am, the shortstop of the future in my first at-bat and they’re booing me."

He had taken his greatest memory in the sport, rewritten it, and begun telling it as tragedy.

Around that time, he asked the Giants to trade him.

4.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.