1. April In Ohtani

Because of local blackout rules, the Dodgers only exist as a radio team for me. It’s great having one radio-only team. They exist in a different dimension than everybody else. I have absolutely no idea what Andy Pages’ facial hair situation is. I couldn’t guess Landon Knack’s body type within two standard deviations. I only know these guys as characters in a novel that hasn’t been adapted into a TV show, described by the third-person narrators who cycle through the visiting broadcast booth.

The picture I’ve had in my head of Shohei Ohtani this year has been shaped by these voices. At some point each series, every visiting broadcaster notes how uncomfortable Ohtani looks on pitches inside. He’s been jumpy, ducky, he’s been flinching away from pitches that catch the inside of the strike zone, etc. The impression was that Ohtani maybe had something going on with him; maybe even a liability?

When I finally got around to seeing what they were talking about, I saw what they were talking about—Ohtani reacting to pitches in the Statcast strike zone as though they’re going to sheer his hands off:

And Ohtani ducking away from pitches that are up (but not even inside) as though they’re haymakers:

If you come to town and observe this, it’s natural to describe it as something maybe wrong, as an implication. But it makes a lot more sense to think of this as standard Ohtani theater. We’ve already discussed Ohtani’s strange, panic-inducing tendency to act injured after he swings. We’ve also alluded to Ohtani’s charming habit of shouting (unnecessary) warnings at the fans toward whom he has hit a foul ball. He is a ham, or perhaps he has decided that the best way to deal with adrenaline is to let it sit right up against the surface of his body, where it can escape easily through these acts of harmless overreaction.

But in this case there’s one other possibility: Maybe Ohtani wants to get caught looking uncomfortable.

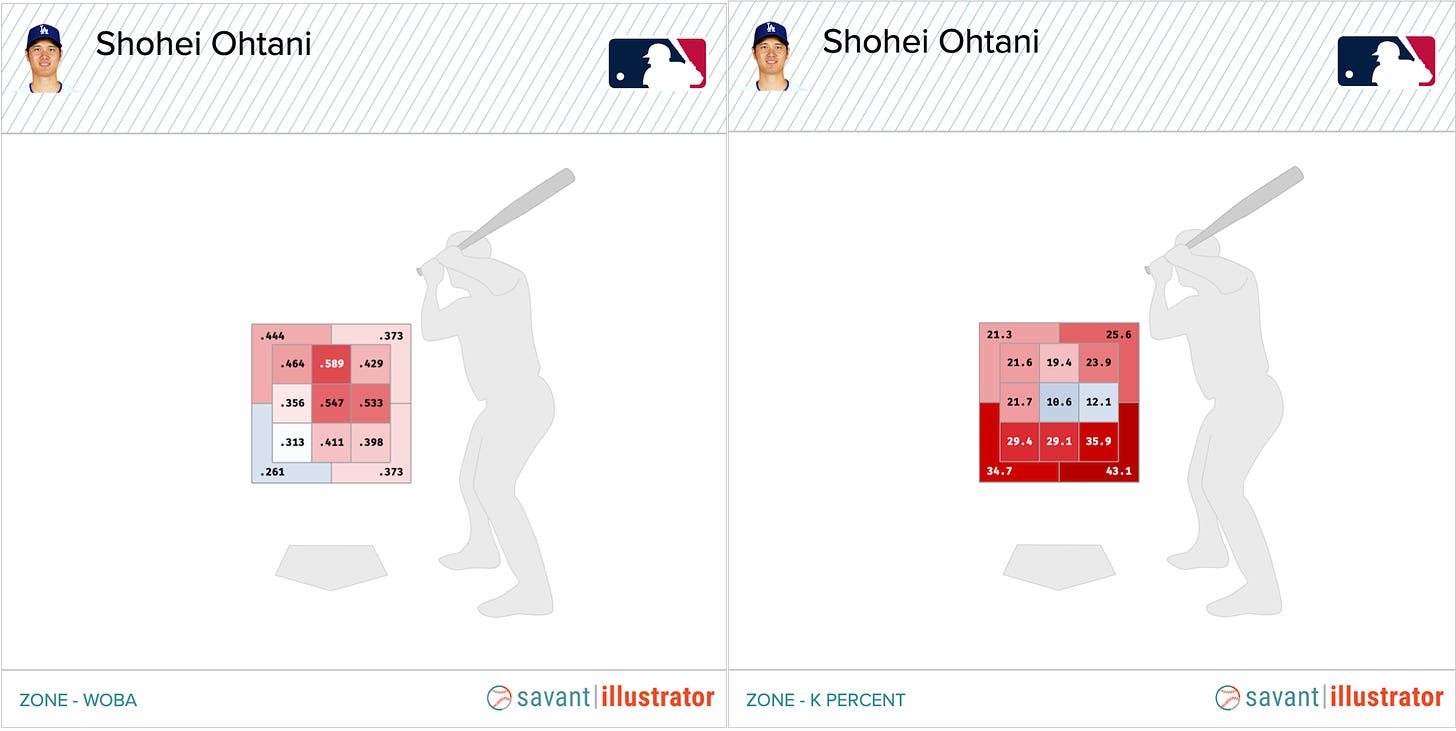

Ohtani hits pretty much everything well, but to the degree his heat maps show a preference, you could put it like this: He’d rather have the ball inside than outside, and he’d rather have the pitch up than the pitch down. By wOBA, those are where the reds are, while by whiff rates those are where the blues and pinks are.

It’s unlikely he’s going to dupe a scout into putting misinformation into an advance scouting report. But pitches and catchers really do observe the batter from pitch to pitch, adjusting based on how comfortable his swings and takes look. Ohtani could be acting out discomfort to try to steal a pitch selection—to get an extra pitch in his hot zone. I’m not going to say it’s working, but the rate of pitches he’s seen on the inside-middle and inside-up parts of the strike zone have increased this year, from 8 percent last year (and 7 percent from 21-23) to 9 percent this year. That’s only about 10 extra pitches in those zones this year, nothing to take seriously as data, but something to watch. Anyway, it only takes one pitch in that region for him to hit a ball 119.2 mph, as he did April 27, the hardest-hit ball of his career so far.

2. April in Catcher’s Interference

Last season set an all-time record for catcher’s interferences and this season is going to blow past it. There was a great piece last year about why and what it looks like. This year’s further developments are less the overall increase and more the specific type of interferences we are seeing more of: Checked-swing interferences and extremely late interferences.

Nine of the 32 interferences this year have come on checked swings, and I’m not talking half-swings—I’m talking swings that wouldn’t have been called swings at all. These are checked swings that have hit the glove after the catcher has caught the ball.

(Last year, through June, there were seven interferences on checked swings. At most two involved a bat hitting a glove that had already caught the ball.)

A few of this year’s strangest- and latest-looking interferences:

It’s all of minor significance for now. But there are two potential consequences looming. These late checked swings look way more suspicious, i.e. intentional, than full-swing catcher’s interferences. On some of these there was insinuative grumbling from the broadcast booths that it looked “almost like” the batter had tried to swing right at the glove, and in once case the manager came out to discuss it with an umpire. I don’t think intentional CIs are here or coming, partly because doing any of the above on purpose would be seen as the bushiest-league move ever, and “that’s bush” still has some dissuasive power in ball. That said: The checked-swing CI looks pretty easy to do, and to get away with. In the right moment, it’d be worth it. And thus, there will be ambiguity, and thus, there will at some point be controversy. I predict a CI-induced brawl in the next three years.

The other is that, if enough of these happen, there could really be a conversation about whether a batter needs to actually swing to have his swing interfered with. It feels like a contradiction to see a home plate umpire rule “no swing” and then moments later put that batter on first base because the catcher interfered with a swing. This might call for a modification of the rule book. The problem is, as we can see from the overhead view of the Volpe swing, sometimes what looks like a checked swing really is a bat coming up against a barrier:

3. April in Play Indexing

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.