Discover more from Pebble Hunting

Moving Pictures About The Catcher's Interference Frenzy

One of the sport's quirky background characters is getting a bigger role.

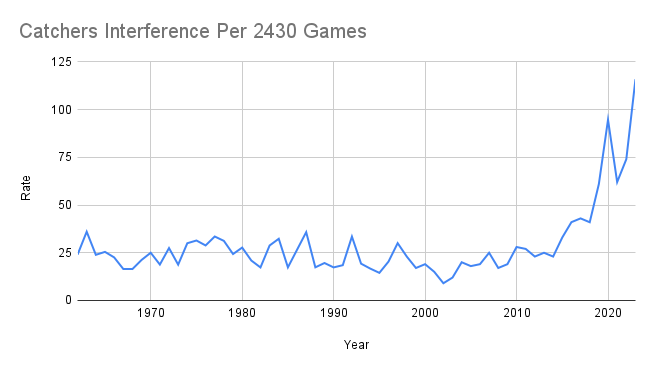

For 50 years, few things in baseball were steadier than the rate at which batters reached via catcher’s interference—around 20 per year, across the league. A catcher’s interference is a fluke, generally an accident, and has managed to exist outside the swings of strategies and styles that affect everything else in the game.

Then in 2015 the majors set a new record for catcher’s interferences, a record that the league then broke five more times in the next seven years. It’s going to get broken again this year, and this time they’re really not fooling around: The 2022 mark will likely be passed sometime in July. Catcher’s interferences are about five times as frequent now as they were, reliably and steadily, from the 1960s through the mid-2010s.

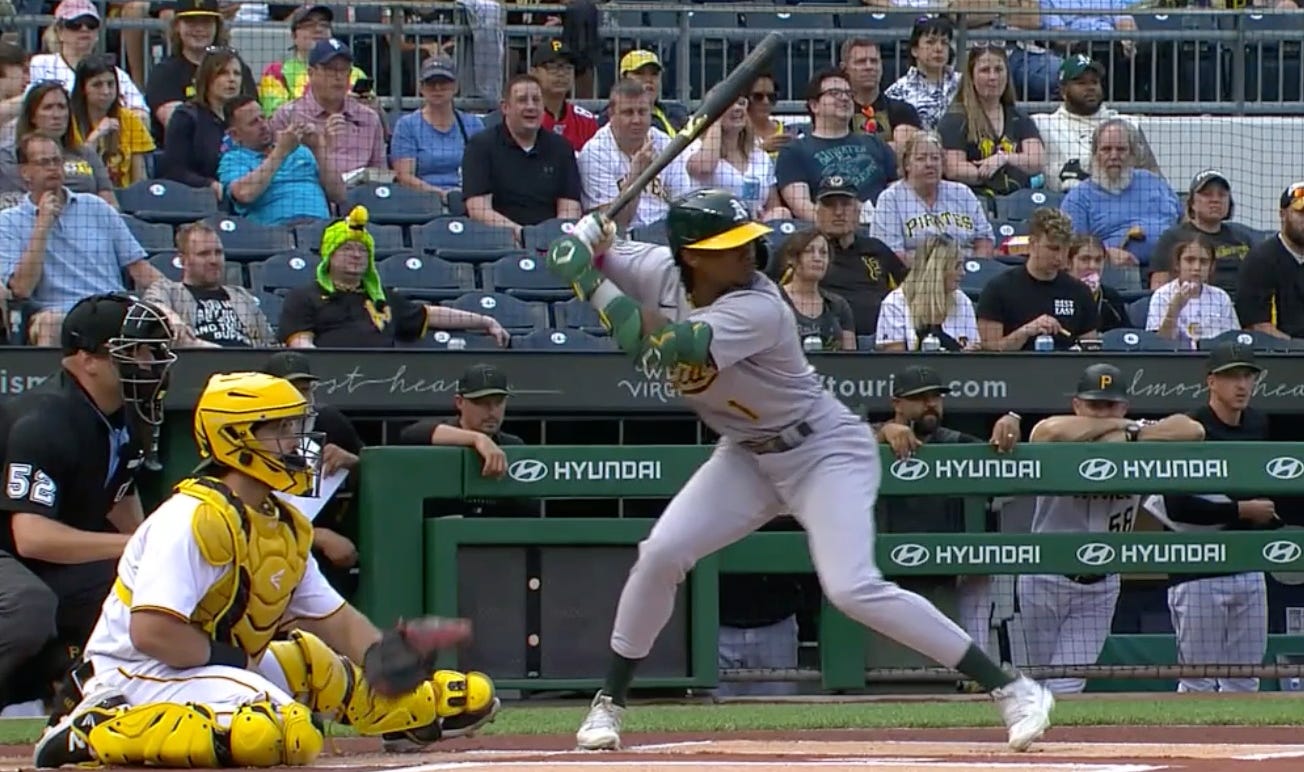

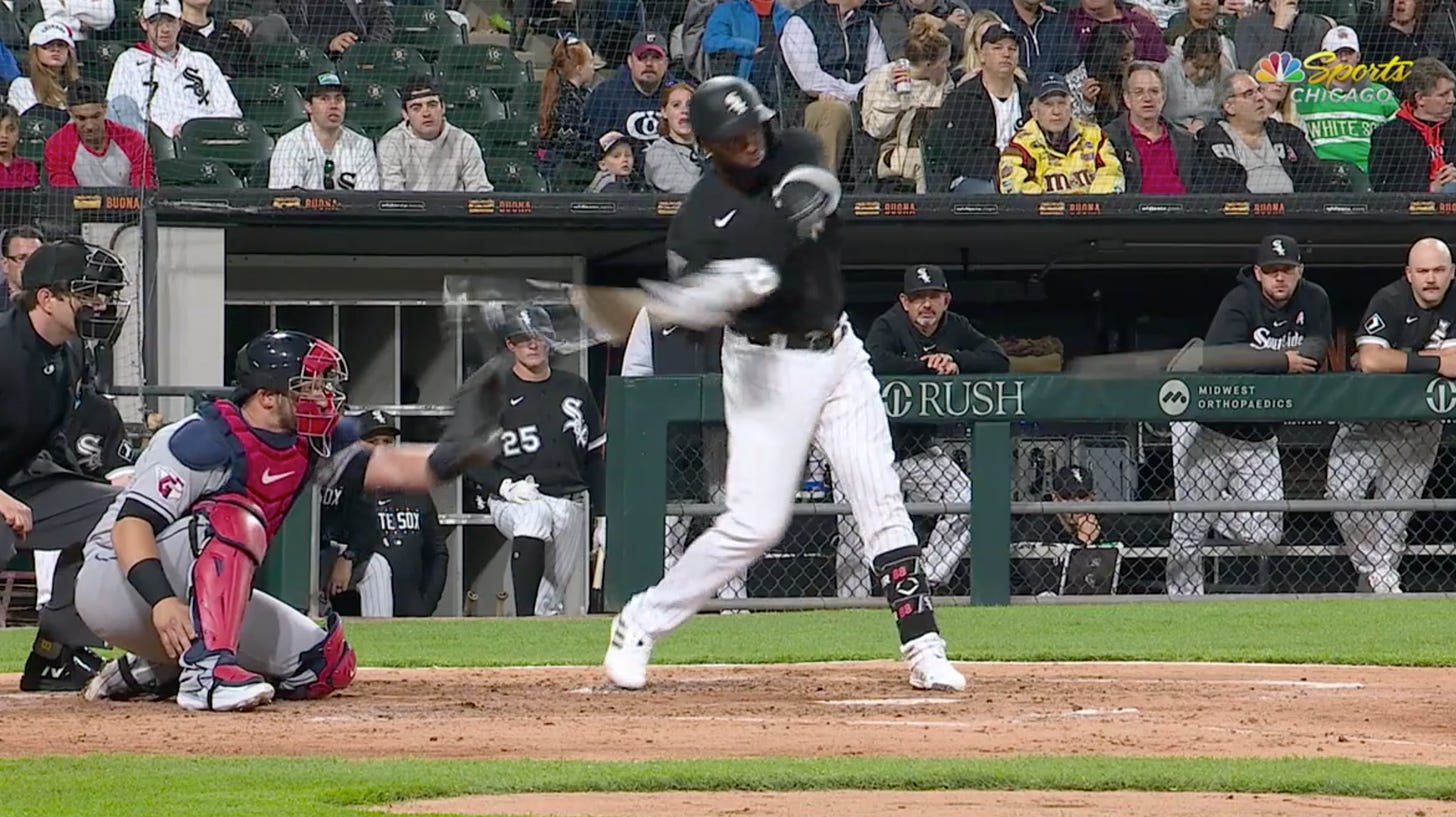

The nice thing about leaguewide trends that involve only dozens (as opposed to tens of thousands) of events is that it’s easy to set aside an afternoon and watch every single example. So I did, just to see what’s interesting, and now we find ourselves writing a newsletter, primarily because: Would you look at how far forward William Contreras’ mitt is!

(You probably can’t see the contact, but yes, Josh Rojas’ bat just ticked Contreras’ mitt and Rojas was awarded first base.)

The conventional wisdom around all these catcher’s interferences is that the emphasis on catchers’ framing technique is the primary cause. Most borderline pitches are moving away from the strike zone as they pass home plate. The catcher, then, wants to catch the pitch before it has had time to move even further away from the zone, to give the umpire a good view of a baseball that’s not too low or too far inside or outside. You can find a lot of examples of 2023 catchers who are astoundingly close to the batter on the plays in question. Look at Austin Hedges!

Blake Sabol’s left foot is actually IN the batter’s box!

Besides setting up close to the plate, though, a more important variable might be the way that catchers reach out for the ball now.

It can be hard to determine just how close to the plate these catchers set up compared to the catchers of yore, because ever camera angle is slightly different and can be slightly misleading. But we can easily compare the mitt movement of Contreras, in that GIF above, to this clip of Bengie Molina from the 2010 World Series:

or this clip of Welington Castillo, waiting for a pitch that will never reach him in 2015:

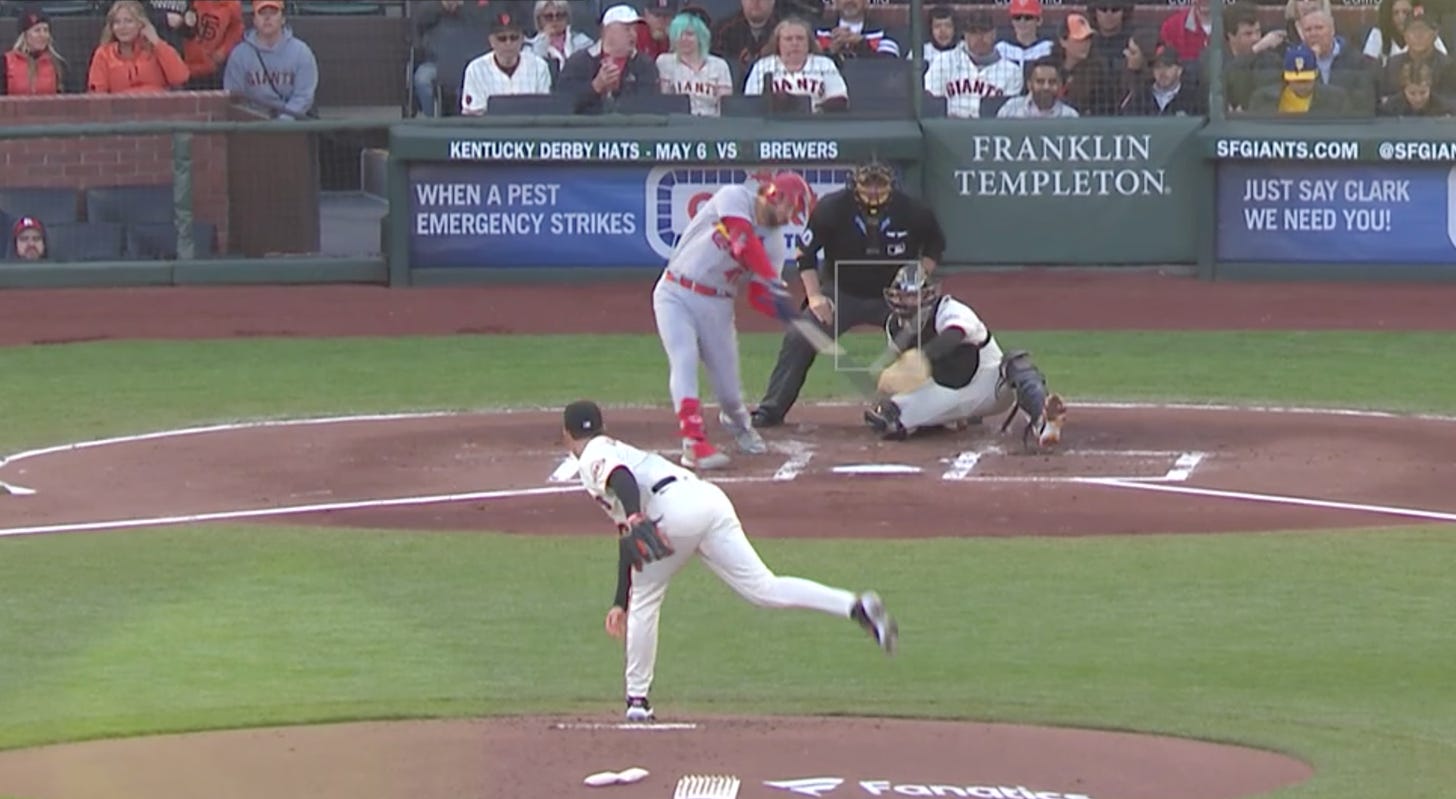

As the pitch is crossing home plate, Castillo’s and Molina’s mitt hands are basically still, while Contreras is stretching his mitt hand into the hitting zone, trying to penetrate the strike zone just after the swing. That seems crucial to a lot of the CIs I watched from 2023. We see this, for instance, in this catcher’s interference by Conteras’ teammate, Victor Caratini:

If Esteury Ruiz had hit that pitch when it was front of the plate, Caratini would have been fine. But because Ruiz’ swing was slightly late, Caratini’s mitt had traveled—what, six extra inches forward, just in that single frame. By the time Ruiz swung, Caratini was in the swing plane, and got ticked.

That’s more or less my catcher’s interference hypothesis: It’s the reach forward that’s encouraging this spike. Catchers are trying to sneak into the strike zone right behind the batter’s swing, like a burglar sneaking past the security gate after a car has driven through. It usually works! It helps the catcher give the umpire a great frame of the pitch while its still in the strike zone. It’s just a very delicate maneuver, and when a batter swings late—or a batter makes a checked swing on an inside pitch—or a batter lets the ball travel deep—or the catcher miscalculates slightly—then the catcher has snuck into the strike zone right ahead of the batter’s swing.

Shohei Ohtani has received five catcher’s interferences this year as a hitter. All five of them came on late swings, pitches he fouled off toward the third-base dugout or thereabouts. Four of them came with two strikes, as he made a last-second protect swing.

If he hadn’t been late, the catchers might have been fine. If the catchers hadn’t been reaching forward, the catchers might have been fine. Alas, for them.

I’m convinced that virtually all of the catcher’s interference this year are accidents—that the batter wasn’t trying to get to first base via this loophole, as many of us often wonder about. But a small number of players end up drawing a disproportionate number of catcher’s interferences because their swings are suited to this outcome.

Luis Robert has five catcher’s interferences this year. All of those CIs came on, basically, the same pitch: fastballs in the middle of the zone or the top of the zone. If a player were plotting to get catcher’s interferences, he wouldn’t know what pitches was coming or where they were being delivered, and we wouldn’t expect his CIs to cluster around one pitch type like this. What seems to be happening with Robert is that there is a particular pitch type and location that he stays back on.

His bat comes through the hitting zone late. It’s part of his swing’s fingerprint.

I watched 55 catcher’s interferences from this year. I could be persuaded that maybe as many as three were intentional on the batter’s part, but most likely I’d say it’s either zero or one. If it’s one, the one would be this one, by Jonathan Davis:

It looks nothing like a natural swing—James Fegan, writing for the Athletic, called it “hideously late”—and even if we think he was protecting the plate with a last-second swing on two strikes, it’s odd that there is no follow through, no wrists turning over. This looks like he decided not to swing and then reconsidered at the last second and then reconsidered again. Well, actually, it looks like if somebody had a plan to get on base via catcher’s interference, but who can say.

If we thought that batters were targeting catchers’ mitts, we might hypothesize we’d see lots of catcher’s interferences in high-leverage situations, when there’d be more incentive to do whatever it takes to reach base. We don’t. The median leverage for catcher’s interferences is .97, about average. In other words, batters are not drawing more catcher’s interferences at more opportune moments. (Luis Robert, Kyle Tucker and Esteury Ruiz, all of them catcher’s interference specialists this year, have all drawn catcher’s interferences in meaningless blowout situations.)

But Davis’ Marlins were trailing by a run in the ninth inning with one man out and nobody on base. This was a huge situation for a catcher’s interference. Davis fell behind in the count, and with two strikes he got bailed out by this catcher’s interference and reached base as the tying run. It was what you’d call a clutch catcher’s interference, whether or not it was intentional. The Marlins would rally behind it; three batters later, Davis would score, and the Marlins would win the game that inning. This is Davis’s only CI this year.

But batters take awkward swings all the time, especially with two strikes, and Davis might have just been locked up by the pitch, trying to get off any swing at all. And it’s not the weirdest catcher’s interference of the year. For that, I’d probably name Jeremy Peña’s, a catcher’s interference on a ball.

As in, the umpire ruled Peña didn’t swing, and yet subsequently—after Peña argued that he’d hit the mitt nevertheless—that his swing was interfered with. We’re lucky the universe didn’t implode.

And as far as no-swing catcher’s interferences go, Edmundo Sosa swung way less than Peña—

But he managed to touch the catcher’s mitt, and so: To first base, friend.

There’s a hypothesis out there that the new pickoff restrictions this year, which were designed to encourage more base stealing, have sent the CIs even further upward. Catchers, trying to throw out runners, might be reaching forward to get the ball as quickly as possible, trying to neutralize base stealers’ new advantage. It’s a thought. But of the 55 CIs I watched, only one was with the runner going.

Now, what is true is that catcher’s interference happens more often with runners on first base—about 60 percent more often this year. So perhaps catchers are setting up closer to the plate in anticipation of steals, creating more CIs whether or not the CIs actually happen when the runner is going. But that has always been the case. (Last year, without the new pickoff restrictions, there were twice as many CIs with runners on than without.) So, in other words: Potential base stealers make catcher’s interference more common, and always have; but the new rules this year don’t seem to have exacerbated that.

[5/7/24 Update: If you want to read a little more, I wrote a little more.]

(Thanks to Nate, who nudged me to write this with an emailed subject-lined “Year of the Catcher's Interference?”)

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting

I'm writing about baseball & the good life. Contact at pebblehunting@gmail.com.

Wow... this was an amazingly (or unfortunately?) well-timed re-bump of this article.

Also, Sam… are you a Rush fan?