Installment 11:

“When Mike Trout reported to spring training in mid-February 2020, he had more career WAR through the age of 27 than any player in Major League Baseball history.” —Me

OR

"Since 2014, Mike Trout's 151 home runs are the fourth most in baseball." —Fun Fact on the Angels’ Stadium scoreboard, May 2018

1.

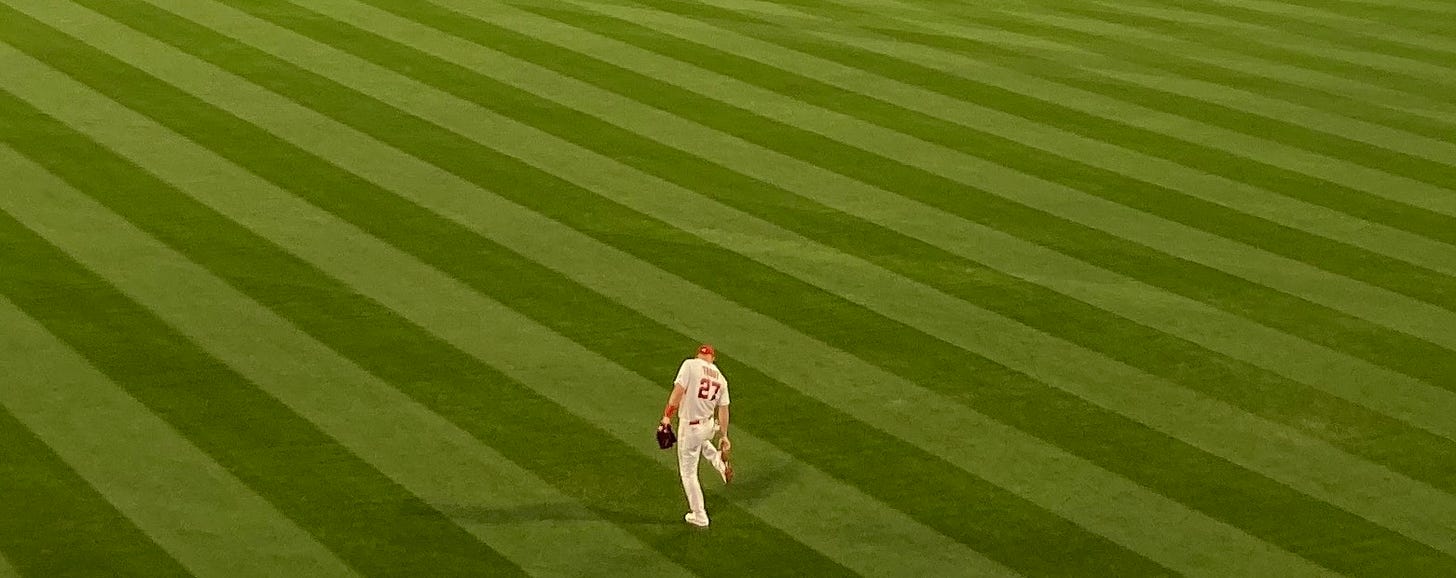

When a game begins, Mike Trout is in center field. In the top of just one first inning, he: kicks grass, smoothes kicked grass, stares into his glove, fiddles with straps of glove, removes glove, checks the count on the left-field scoreboard, checks the hitter’s stats on the right-field scoreboard, randomly salutes at nothing, checks his belt at least 10 times, unclasps and reclasps it, salutes the number of outs to his corner outfielders, signals to the dugout to get his defensive positioning, spits a bunch, blows bubbles with his gum, feels his glove, taps his glove, takes a demonstratively deep breath, and keeps looking around like he thought he just heard somebody call his name, which, to be fair, happens a few dozen times a game just within his earshot.

He has more energy than one can use sensibly. During the National Anthem, he usually looks like a windsock in a row of fence posts. When he jogs toward the dugout after a half-inning in the field, he’ll just randomly veer—sometimes to avoid the infield dirt, sometimes onto the infield dirt, only to veer seems to be the point. He pays close attention to surfaces that have nothing to do with him. Once, after he tried to steal second base and the pitch was fouled off, he stopped maybe 60 feet from first base and smoothed a spot of the infield dirt with his foot. He’ll probably never stand on that spot of dirt again, but he saw something wrong and he had time. So he fixed it.

Late one game, he reaches down and picks up what looks like a blade of grass and puts it in his back pocket. You actually see this a lot if you’re watching him through binoculars. You see him running to center field and he suddenly stops 10 feet past the infield and picks something tiny up and tucks it in his pocket. Or you see him craning his neck between pitches and suddenly he leans over with his bare hand, grabs something, stashes it away in his pocket. There’s nothing out there but grass. What’s he want with grass?

2.

No baseball player and baseball statistic grew up as symbiotically as Mike Trout and Wins Above Replacement did. The all-in-one value stat had emerged slightly before Trout, but in his 2012 rookie season, WAR founds its killer application. By counting everything, a statistic was, for the first time, able to be cited conclusively1 to show that one player was more valuable than another, even if they played different positions, had different skills, had different workloads, and so on. So while Miguel Cabrera won the Triple Crown in 2012—the greatest feat possible under the pre-WAR rules of stat-comprising—Trout was, to the emergent baseball fan, obviously better. We knew this thanks to slightly abstract details like park factors and positional adjustments, and previously undercounted events like scoring from first on a double, and a belief in the concept of defining a clear and universal objective (producing/suppressing runs) and then measuring each player’s incremental progress toward that objective. WAR got Mike Trout on the cover of ESPN Magazine, which served as a national advertisement for both entities: “WAR Is The Answer” was the headline of the accompanying article, which, incidentally, I was the author of.

Like citing scripture, WAR isn’t compelling to somebody who doesn’t accept its sacredness. In what we might call the Trout paradox, the more that went into WAR, the less we actually had to say about him, because everything was already in the WAR. Without WAR, a partisan could have spent several hours demonstrating just how many ways Trout was better than Miguel Cabrera or Bryce Harper. With WAR, the partisan could only get exasperated: All that data in the vat and some people still wouldn’t gulp it down.

“When do I get to quit hearing about how great Mike Trout is,” my uncle cried out one day, as he and my dad and I were having the “best player in baseball” debate. Obviously Trout is great. Uncle knows that. But enough fun facts about his WAR!

At some point during Trout’s peak, and continuing through 2023, I developed an occasional habit of taking a pair of binoculars out to Angels games and watching nothing but Trout. Maybe a dozen times—from batting practice through that night’s game—whether he was in the field or at the plate or in the dugout, I watched him. (When he jogged down the tunnel between innings to watch video of his previous at-bat, I used to stare into the dark of the tunnel, awaiting his climb back up the steps. In later years, I would use this time to give my eyes a break.) The idea was to see the WAR, and to develop something like John McPhee’s seminal Bill Bradley profile—to explain how Trout produced all the wonderful baseball value we’d been counting. But it became more interesting to see Trout producing something we weren’t counting at all, something fundamentally outside the realm of counting. Call it the Trout Vibe, or the Trout Experience, or just the Trout Relationship To The World. Unlike his WAR, it was something that was unperformed. It was just Mike Trout, without an objective, being his self, at play.

3.

After each half-inning that he plays the field, Trout puts his cap and glove in the same spot at the top step of the Angels’ dugout. One game, he was involved in a confusing play in center field—a ball had rolled along the top of the wall, over the yellow home run line, then back into the field of play. When Trout got back to the dugout after the third out of the inning, his cap and glove in hand, a small group of teammates was waiting for him with questions about what had happened, what the umpire had said, etc. But they were all standing right in his cap-and-glove spot.

Trout talked to them for a moment, answering questions, describing the play, holding onto his cap and glove. Then the questions ended, but the teammates still stood where they were, discussing the play amongst themselves. So Trout… walked down to the other side of the dugout, still holding his cap, holding his glove. He didn’t shove his teammates out of his way so he could put his cap and glove down. He didn’t even politely ask them to accommodate him. He adjusted. He gave them that space. The best baseball player in the world, but he accommodated them. He walked down to the other side of the dugout, lingered near the batting helmets, talked to other teammates while holding his cap and glove firmly in two hands. The crowd of teammates near the steps dispersed, and when he saw an opening he quickly walked back and finally lay down his cap and his glove.

4.

He looks always eager. When his team is batting, he’ll put his batting helmet on even when there are two outs and his turn in the batting order is still three spots away. In the middle innings of one game, with Trout batting third in his team’s lineup, he was sitting with the no. 2 hitter on the top step of the dugout. The no. 8 hitter was walking to the plate, so Trout’s teammate nonchalantly stood up and went to get his helmet ready. Trout stayed seated on the bench. His leg started shaking a little, then thumping harder. He held out like this for 15 seconds, then followed his teammate to the helmet rack to put his helmet on. The chances were perhaps 1 in 30 that he’d bat in the inning, but it is as though he might have willed it into existence by his readiness. He got his helmet and bat, but the area was crowded with all the batters who were scheduled to bat before him. So he went back to the bench to wait, helmet on, bat upright, leg a’thump.

5.

When he gets to the on-deck circle, he bends down to get a donut for his bat, and while he’s tipped upside-down he gives a little pinky-finger wave to a young fan sitting up against the net. Any wave from Mike Trout would be nice, any acknowledgement, but Trout is really good at all of this. He waves from this disorienting, unnatural position, inverting the power dynamic and turning Trout into the kid and the kid into the not-nervous normal one. Plus, he waves with his pinky. He’s a marble statue of a man, but he activates the most delicate part of his body to say hello. The kid smiles, you smile, then Trout smiles.

When he’s doing warm-up throws between innings, it comes time to throw the ball into the stands for a souvenir (a friendly deed which, it should be noted, many/most outfielders don’t even bother with). He is always the one who does the throwing into the stands, which doesn’t seem like much, but a ball thrown to you by Mike Trout is obviously much different than a ball thrown to you by Hunter Renfroe, no offense Hunter Renfroe. By taking that role, Trout creates wealth out of thin air. He also makes sure he throws the ball from far away, way farther than he has to, because the long flight of a ball thrown by Mike Trout multiplies the personal thrill of catching that ball, like compounding interest.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.