The cartoonist and author Randall Munroe once did the math and concluded that it would take 45 years to actually read “all the laws” that apply to each of us as citizens. That doesn’t even include all the assorted non-state rules: the iTunes terms of service we agree to, “i before e except after c,” our own New Year’s resolutions. There are a lot of rules in a lot of rulebooks.

In baseball, there is an Official Baseball Rules book, which I consult often. But there are other documents that also dictate what can happen on a ballfield: There are collective bargaining agreements for the players and for the umpires, there’s an MLB Constitution, there are countless umpire instructions and directives that are sent out by the Commissioner and have the force of law whether or not we the people ever get to read them. There’s also an Umpire Manual,1 which in my opinion is actually the most interesting of them all, because it gets to what makes baseball baseball: It’s weird, it’s unexpected, its potentialities are impossible to grasp, it is sometimes interrupted by birds.2

The Major League Baseball Umpire Manual, 146 pages long3, comprises three sections:

The first dictates umpire behavior, e.g. umpires aren’t allowed to have visible tattoos. Huh!

The second interprets or clarifies certain rules, and anticipates strange contingencies, e.g. it specifies that a manager is allowed to leave the dugout to ask for clarification on any balk call except for a step-balk. Interesting?

The third describes the mechanics of a four-umpire system, diagramming various coverage rotations and how to measure the length of a glove.

I watched August baseball with these 146 pages in the front of my mind. I’d like to talk about three brief passages from this manual, with pictures and videos as useful.

***

1.

“MLB Umpires are expected to increase the assertiveness of their call (signal and voice) as the play becomes closer or more exciting. A casual, laid-back mechanic is not appropriate in a crucial, close play, nor are over-elaborate, excessive signals an acceptable technique.”

There are umpire actions that you’ve seen one million times without noticing exactly what you’re seeing. For instance: Take a moment, maybe close your eyes, and picture a home plate umpire pointing to a base umpire for an appeal on a checked swing. Okay? Now, let me ask you: Which hand did the home-plate umpire point with, or did you not bother to distinguish? Presumably you didn’t bother to distinguish, and that’s wrong. The umpire always requests with his left hand.

Of course, this makes sense now that you know about it: A point with the right hand is how an umpire signals a called strike, so by appealing with the left hand he avoids any potential for confusion. That’s in the manual.

Similarly: I’m sure I’ve noticed that sometimes umpires will signal safe (or out) with more enthusiasm than they do at other times. But a) I probably didn’t notice that these variations are more or less uniform across all umpires, rather than reflective of different umpire’s different temperaments, and b) I definitely never clocked that these variations are intentional and prescribed.

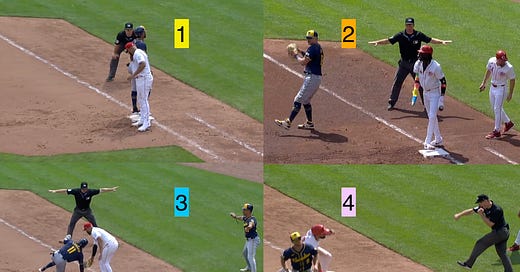

But sure enough, when you see it, you see it. Consider four pickoff attempts in a recent Reds/Brewers game, all of which involved a tag being applied. These go: Back standing, easily back diving, barely back diving, and out diving.

There are two axes here: How close the play is, and how significant the call. An out call is much more significant than a safe call, because an out call transforms an inning, while a safe call merely preserves the status quo. As the plays get closer in that collage, the calls get more demonstrative. And when the situation gets wholly upended by the runner being thrown out, the umpire gets his entire body involved, danged near leaves his feet.

That’s in the rules!

It’s a fascinating directive. It suggests, for one thing, that umpires are supposed to be part of the entertainment. Just as the servers at a theme restaurant are mostly there are make sure we get our food and pay for it, they also have a role to play in maintaining the fiction that we’re aboard a pirate ship or whatever—so they say “Arrrrr.” Umpires, similarly, are told via this instruction in their manual that they are not fully outside the fan-entertainment experience. They are asked to help maintain the fiction that this stuff is really exciting. When we the fans are supposed to be excited, they the umpires are also supposed to act excited.

Actually, more than that, I think the directive is about projecting confidence in the call. One of the very first things this manual says—second paragraph!—is that “MLB Umpires should display… a confident demeanor in order to project a professional appearance.” A few grafs later: “MLB Umpires should remain calm, confident and non-confrontational in order to maintain an appearance of fairness and impartiality.” And then, a little later: “All signals should project decisiveness to the teams, fans, and media.”

So, in a sense, the league has directed umpires to act more confident when plays are close, when they’re actually less confident. This is a lie, kind of, but it’s a lie with benefits: If a call is going to go against you or your team, you’d probably rather it come from somebody who looks decisive, rather than from somebody who looks like they have no idea and are flipping a mental coin.

***

2.

“When a batted ball is rolling fair down the foul line between home plate and either first or third base and a fielder stoops down over the ball and blows on it or in any other manner does some act that in the judgment of the umpire causes the ball to roll onto foul territory, the umpire shall rule a fair ball. The ball is alive and in play.”

The joy of this manual comes, in part, from realizing that virtually all of the rules clarifications are included because at some point something must have happened. In this case, what happened was, in 1981, the Mariners’ third baseman Lenny Randle saw a ball rolling down the line fair—it was going to be an infield hit—and he dropped down to the ground and blew it foul. With no rule in the books at the time, the umpires could have gone in either direction, but they decided against Randle and called it a hit. But one umpire can’t establish precedent on his own. To be certain this is how it should/would be ruled every time, somebody had to put the rule down in a rulebook. That’s why this rule is here.

It exists in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.

So, if you want to appreciate how strange baseball can get, how many contingencies are lurking, then just read the rule book, or in this case the Umpire Manual. What strange days must have happened in the past to require these rules:

“If the pitcher places the resin bag in his glove… it is a balk.”

“The catcher may not substitute a fielder’s glove or a first baseman’s mitt for a catcher’s mitt during… any individual play.”

“Players are permitted to use reference cards during games so long as… there is no attempt made to alter the baseball using the card.”

A manager may ask the umpire to check the length of the opposing team’s gloves only twice per game.

Those are the weird things that have already happened, presumably.

But the most important single rule in this whole manual might actually be this one, which relates to a first baseman’s attempt to block the baserunner’s view of a pickoff attempt by standing between him and the pitcher:

Ruling: While Official Baseball Rule 5.02(c) allows a fielder to position himself anywhere in fair territory, if the umpire deems the fielder’s actions are a deliberate effort to block the runner’s view of the pitcher, it is illegal and clearly not within the spirit of the Rules.

That rule isn’t all that important in and of itself, but the final eight words seem to me incredibly important. That’s the only time in the Umpire Manual that the phrase “spirit of the Rules” is invoked. The phrase doesn’t appear in the Official Baseball Rules at all.

By acknowledging it here, the league has tacitly approved of using this common-sense standard when some contingency isn’t specifically addressed4. This is important, because for all the hundreds of situations that this book tries to anticipate, there are millions more that it hasn’t. Without the phrase “spirit of the rules,” umpires would left with only an inadequate map. Consider, for example, the rule that we began this section with. Reacting to the Lenny Randle situation, the league added a note to the rules that would make it very, very clear: No blowing a fair ball foul. But that means the rules are totally silent on this situation:

Could Pete Alonso have dropped to the ground and blown that ball fair, to get out the batter who hadn’t bothered to run out of the box? The rules are clear about which direction you may not blow the ball. Does that mean its silence on blowing the ball the other way make that legal? You could argue it that way!

But, by giving the umpires some “spirit of the rule” discretion, it puts some authority behind an umpire’s decision in any unaddressed situation. It also makes a lot of these hypotheticals pretty easy to call. The spirit of the rule is “no blowing.” Pete Alonso couldn’t blow.

***

3.

“MLB Umpires are entrusted with the authority to remove any participant from a game. This responsibility should never be taken lightly.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.