Do They Still Makes Messrs. October?

Corey Seager, and the challenge of crowning the new postseason greatest.

You might have heard the story of how the nickname Mr. October was born: As an insult. It was the off-day after Game 2 of the 1977 World Series. Reggie Jackson—who to that point in the 1977 postseason was hitting .136/.269/.136—was feuding with Billy Martin, his manager. That led to the Yankee catcher Thurman Munson—who hated Jackson—going on a long rant to reporters, which concluded (per newspaper accounts the next day) with this:

"I've just got to laugh. Reggie hasn't been doing as well as he thinks. I guess Billy doesn't realize that he's Mr. October. That's what Reggie called himself, wasn't it, Mr. October?"

Over the next four games, Jackson went 8-for-14 with five homers, including the first three-HR game in the World Series since Babe Ruth—a World Series clinching performance in which he saw three strikes all game and hit each one out. After that, newspaper writers adopted the nickname sincerely, as a celebration of what they’d just seen. And now it’s on Jackson’s Hall of Fame plaque.

There’s truth to that telling, though perhaps not the whole truth. Munson in that quote didn’t claim to have made up the nickname—he referred to Jackson calling himself that. And in a different newspaper account of the rant, Munson was quoted saying “I guess Billy just doesn't realize that Reggie is 'Mr. October.' I read that somewhere." Implying, again, that the nickname predated Munson’s smear. Another newspaper that week referred to Jackson as “the man his teammates call ‘Mr. October’ because of his record of performing well in post-season play,” suggesting it really did exist as praise, beyond Munson wielding it as insult. And still another said: “‘Mr. October,’ they called him in Oakland, where his World Series performances carried the Athletics to three world championships.”

Which is just to say that it’s impossible to separate the title “Mr. October” from the context of the moment. Jackson wasn’t called Mr. October because, in his career, he hit .278/.358/.527 with 18 home runs in 77 postseason games. The nickname was born only halfway through that statistical record. (Jackson was a career .250/.331/.421 hitter in 39 postseason games when Munson said the thing, and .279/.358/.539 when it became his forever nickname four games later.) And it likely took hold through some combination of sincerity, irony, self-promotion, success, failure, and success. Ultimately, it captures a condensed period during which Jackson had the chance to either live up to the nickname or crumble1 under it, and which he capped off by producing the greatest single-game postseason performance any hitter ever had.

/\

\/

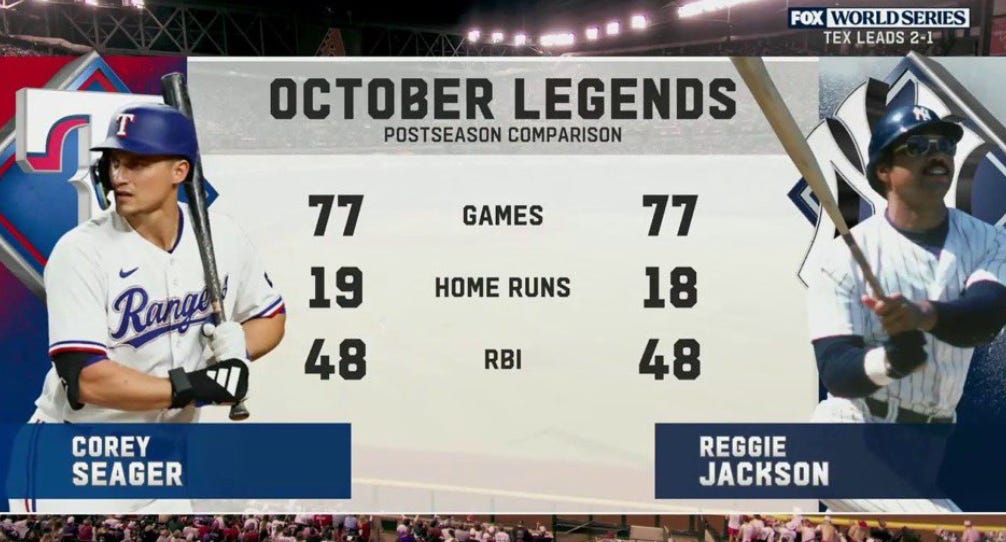

During Game 4 of the World Series, you might have seen this broadcast graphic:

And in all of the hubbub around Seager’s second World Series MVP performance, you might have seen the tweets and articles from the Athletic, Forbes, MLB’s Spanish-language tweeting account, Fox Sports and the LA Times—among countless other social users—that declared Seager the new Mr. October, or Mr. October 2.0, or similar.

I said a few weeks ago I think records should probably be reset every 50 years or so, and I suppose that also applies to Greatest Of All-Time-type titles. I wouldn’t recommend actually reassigning the man’s nickname while he’s still alive and thriving, but finding a modern heir to the title of postseason GOAT seems appropriate. But the problem with crowning Seager, or any other hitter—and I’m only considering hitters here, because taking control of a postseason is fundamentally different as a hitter than as a pitcher—is twofold:

Nobody has done what Jackson did.

Or too many people have.

Besides Seager, I can think of nine 21st Century hitters whose postseason numbers compare favorably to Jackson’s, and who I could plausibly argue stand or stood above all the others:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.