Discover more from Pebble Hunting

Two outs, first inning, Game 5 of the National League Championship Series. The Phillies have runners on first (Bryson Stott) and third (Bryce Harper). Stott takes off stealing, the pitch is a strike, catcher Gabriel Moreno throws to second. It’s a pretty good throw, low and tailing right into the baserunner’s slide path—except Stott isn’t sliding. He isn’t there at all. He has stopped halfway, as Harper has shot off toward home. Second baseman Ketel Marte’s job changes—now he has to get the ball back to the catcher before Harper can score. Marte reaches to field Moreno’s throw, low and to his side. His rushed throw back home is also low and tails just enough that Moreno biffs it. The ball skitters away. Harper scores. Stott ends up at third, Phillies up 2-0.

By cWPA, this was the 17th most consequential play of the Phillies’ season, bigger than any play in the regular season, bigger than any play in the Wild Card round, bigger than all but one play in the Division Series.

It’s a play that the league, and especially the Phillies, had been building toward all year. What’s interesting is how easy it was to pull off—much easier than, say, Kyle Schwarber’s home run in the sixth inning, or Zack Wheeler’s strikeout of Christian Walker in a huge spot in the bottom of the first. Stott didn’t even have to run the whole way to second. Harper didn’t even have to beat the throw. All the Phillies had to do was put a little pressure on the defense and the defense gave them the run.

**

As long as I’ve been baseballing, the first-and-third situation has been what separated the pros from the amateurs. In youth sports, first-and-third, like the synthetic element Darmstadtium, has a half-life of about 14 seconds: It’s an automatic, immediate stolen base situation. If the catcher’s prefrontal cortex has developed enough to produce impulse control, there be no throw to second. If there is a throw, the runner on third will break for home, he will score before the return throw home, nobody will be put out, and the coach will remind the catcher, a bit more tensely than intended, especially if it’s his own child behind the plate, not to throw to second in the first-and-third.

A less exaggerated version of that is true in high school, too, and to some degree even in college, according to journalist Mike Guardabascio, an expert at all three levels. (He coaches youth ball, and, as co-founder of the562.org, covers the other two in Long Beach, California.) “Almost always, they’re just letting him take second,” he said. “Even with good defense in Long Beach, consistent college-level infielders, the chance you’re making both those throws in time is still very low. It’s a trap move.” The “trap” of it was the premise of the Skunk In The Outfield play that I once wrote about: First-and-third is actually better than second-and-third at lower levels, because the other team might make a dumb mistake while you’re on your way to second.

That is not true in the majors. In the majors, two strong throws are very easy to make. The runner on first in a first-and-third can’t just take second base whenever he wants. Or he couldn’t. Increasingly, he can.

In 2023, there were 521 successful stolen bases in the first-and-third situation. That’s a league record, at least going back as far as 1960. About 10 percent of the time a team got into a first-and-third, it attempted a steal; that rate is also a modern record.

2023: 10.1 percent

2020s: 8.3 percent

2010s: 6.6 percent

2000s: 5.1 percent

The spike in 2023 partly reflects loosened basestealing conditions overall, but it also reflects a burst of enthusiasm for first-and-third basestealing among certain teams. The Guardians, for example, went 34 for 35 stealing bases in first-and-thirds. The Nationals went 33 for 36, taking off in 18 percent of their chances.

The Phillies were most aggressive of all: When they had runners on first and third, they took off 20 percent of the time, going 33 for 35. In the postseason, they took off 30 percent of the time, going 5-for-5.

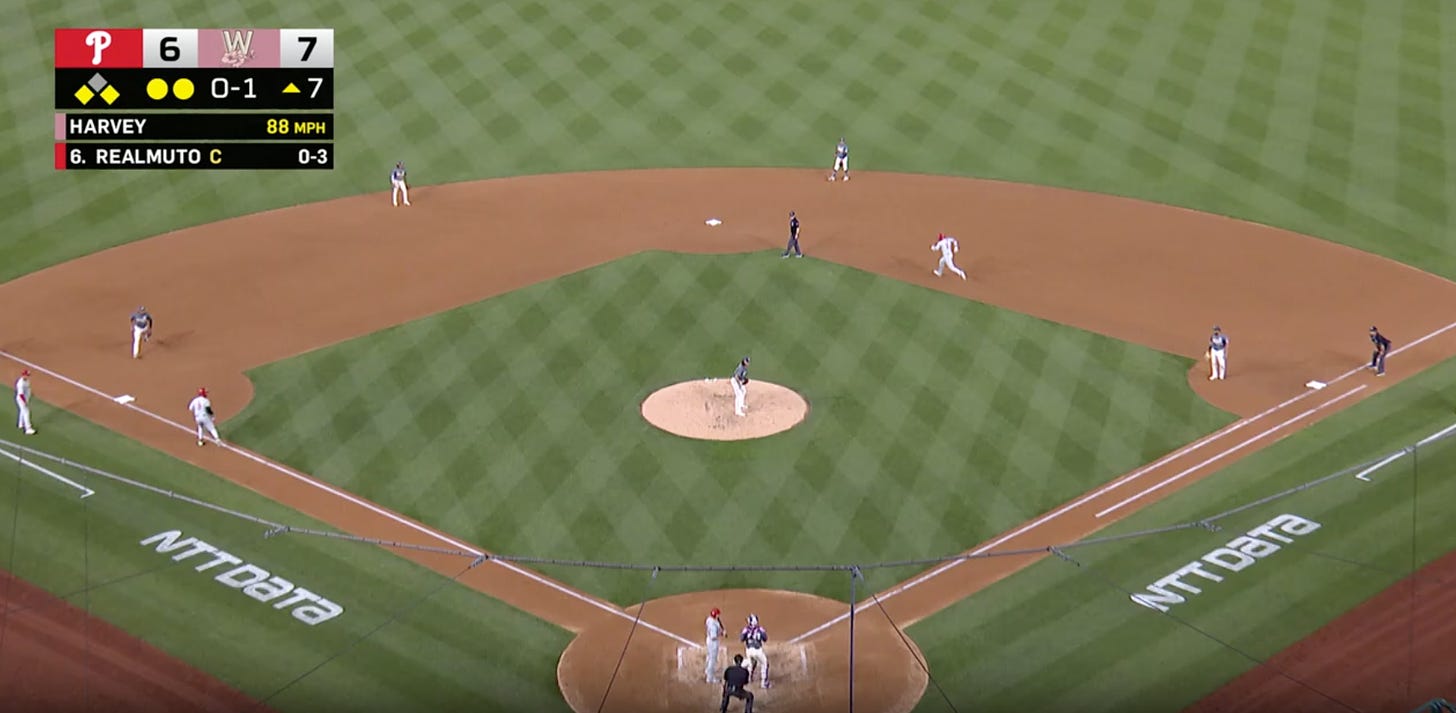

In his entire 10-year career before 2023, Nick Castellanos had attempted three stolen bases in first-and-third situations. Then, as a Phillies, he stole three in first-and-third situations in June 2023 alone. In the first of the three, Castellanos took off at a lope. The catcher pumped as though he might throw, but there were no infielders covering second base. Castellanos, representing the go-ahead run in the seventh inning, was allowed to walk into scoring position while everybody just watched:

In the second one, Castellanos took off and stopped partway, begging for the throw. The catcher bluffed an enthusiastic pump fake to second, then turned immediately to third to see whether he had tricked the runner on third into breaking for home and running into an out. He hadn’t, and with a left-handed batter up the third baseman wasn’t very close to the base anyway.

In the third instance, Castellanos took off, hesitated partway, and the catcher didn’t even bother to bluff. He instead focused on trying to frame the pitch, which was only a few inches outside (but was called a ball). Again, representing the go-ahead run in the later innings, Castellanos got to walk into second.

Castellanos isn’t fast, he isn’t a basestealer—he was actually pinch-run for later in one of these games—and he wasn’t even running hard. He was actually trying, in all three cases, to get to second as slowly as possible, to draw a throw. And even though his run meant a lot in all three cases, the defense still wouldn’t try to get him out. To do so would have risked letting the runner on third break for home, and forced the defense to make two good throws to stop the run. The defense didn’t think it could do so. Little League logic!

Whenever the Phillies tried to steal in first-and-third, the opposing team almost never threw to second. Almost half the time the opposing catcher would bluff to second; almost half the time the catcher wouldn’t even glance up at the runner; and about 10 percent of the time there was a throw to second. The Phillies were caught stealing twice, but those were exceptions that prove the rule: In one, the runner on first was picked off by the pitcher, not thrown out by the catcher. In the other, the runner on first represented the tying run in the bottom of the ninth—which meant the runner on third was actually irrelevant. It wasn’t a true first-and-third.

***

There are three actors in this play, and each faces one either/or, if/then decision:

1. The runner at first can either steal or not steal. If he steals, then

2. The catcher can either throw to second or not throw to second. If he throws, then

3. The runner at third can either break for home or stay at third.

There used to be a wrinkle of ambiguity to this decision tree, says Jerry Weinstein, a longtime professional manager and coach with the Rockies. The catchers used to look the runner back to third before throwing. That froze the runner and meant he couldn’t get a big break for home, or else risk getting caught by the catcher/third baseman if he did.

“What happened is that teams were finding that when they looked guys back, the delay meant they weren’t being successful throwing runners out at second,” Weinstein says. “So that piece has gone by the wayside. They don’t look the guy back.”

Therefore, “It used to be [the runner at third] didn’t leave until the ball cleared the pitcher’s head. Now people are leaving on release or just before.”

In which case, Weinstein says, it’s practically impossible for the defense to throw the lead runner out at home. “It’s a time and distance game. The throw from home to second is going to be in the 1.8-second range. Then the throw from the shortstop to the catcher is in the 1.5-second range, and then a tenth of a second for the tag. And you’ve got the runner who is running 75 feet, maybe less, and with momentum. Even an average runner on third can beat the play now. Even two good throws will probably not get you out.”

So, going back to that decision tree, but now playing it out in reverse:

3. If the runner on third knows that the catcher can’t look him back, then he can get a huge jump on any throw.

2. If the catcher knows that the runner on third will get a huge jump if he throws, then he can’t throw.

1. If the runner on first knows that the catcher won’t throw, then he can take second anytime he wants, at any speed he wants.

Hence: More steals in the first-and-third, and almost never a throw down to second.

**

But here’s the most interesting part of this: Sometimes the catcher does throw to second, and the runner on third hardly ever actually takes off for home! The Phillies, for instance, drew five throws to second base this year, but their runner on third only took off for home once. (The Harper play in this post’s opening anecdote.)

Which brings us to the Orioles.

Most teams on defense were pretty helpless against the first-and-third this year. But the Orioles were not. The Orioles allowed only six stolen bases in first-and-third—the median team allowed 19—and they caught the runner four times, tied for the most in baseball. The league was 90 percent successful stealing in first-and-third, but only 60 percent successful against Baltimore.

The seemingly obvious reason is simply that the Orioles throw to second.

I was able to find nine of the 10 stolen base attempts the Orioles faced in first-and-third, and of those nine they threw to second eight times. The ninth was a hard pump fake, and even there the decision not to throw seemed more practical than anything: There were two strikes and two outs, and the catcher was in a bad position to throw because he was prioritizing framing the pitch. Also, the runner at first had a great jump.

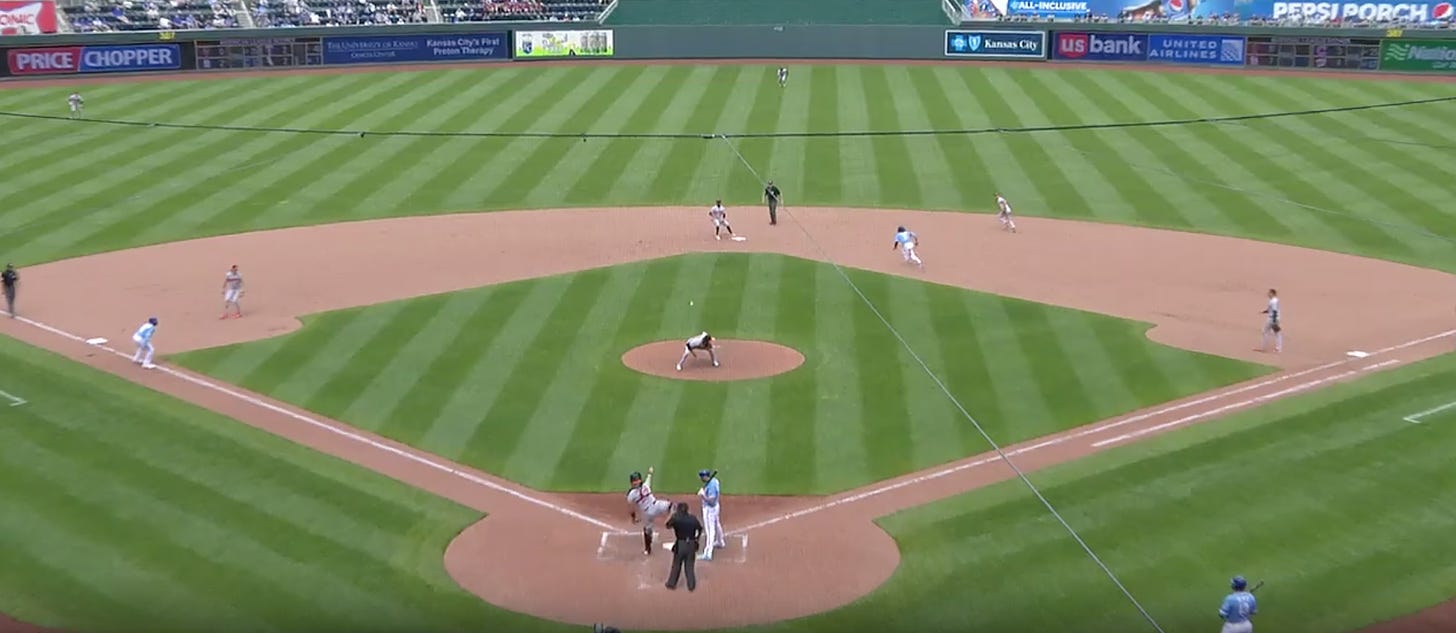

So the Orioles made eight throws to second, and… zero runners broke for home from third. Even when one throw got away from the second baseman, the runner at third didn’t try to score. Not only did runners on third not take off on the catcher’s throw—or just before—but they didn’t even take big secondary leads when the throw cleared the pitcher’s mound:

Why do none of the runners on third try to score, if they’re not even being looked back? It seems like it’s this:

In modern ball, the catcher rarely throws through to second. In modern ball, the catcher usually bluffs to second. So when the catcher starts to “throw,” the assumption is that it’s a bluff.

For now, the Orioles have a small exploit: As one of the only teams throwing through, they get all the benefits of the throw, and all of the benefits of other teams’ bluffs.

So, going back to our decision tree, the order of which has gotten scrambled again.

The league has reached a weird balance, or maybe imbalance: The runner on first can basically take a free base, because a throw is rarely going to go to second, because the catcher is worried about the runner scoring from third, even though the runner on third rarely actually tries to score from third on a throw, because he’s worried the catcher won’t throw through to second. If the catcher knows the runner on third isn’t going to try to score, he can start throwing to second more often (as the Orioles do). But if he starts throwing to second too often, the runner on third will try to score. In which case… we loop back around.

Weinstein thinks we can probably expect even more steals in first-and-third, especially because runners on third can be a lot more aggressive than they have been. Harper wasn’t that aggressive in the NLCS. He started to leave as the catcher Moreno released the ball, but he didn’t have a lot of momentum or conviction behind his jump, and he didn’t beat the throw home. But he still proved how complicated the play can be for the defense. It’s only two good throws, yes. But trying to throw the runner out at second calls for a different type of throw (low, first-base side) than the infielder would prefer if he’s trying to get the ball back to the catcher quickly.

The question is whether the current state will hold. As the Orioles show, “sometimes bluff and often throw” seems to shut this running opportunity down. Not only do the Orioles sometimes get outs at second, and not only do they never allow double steals of home, but fewer baserunners test them at all—teams don’t take the free second base against them, because it’s not free. If more teams do what the Orioles do, though, then maybe the runners on third will start getting more aggressive, and force the Orioles to stop throwing to second…. dang it, back in the loop. I suspect we might do this all year.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris, and of course the Baseball-Reference Stathead tool, for research assistance.

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting

I'm writing about baseball & the good life. Contact at pebblehunting@gmail.com.

But it's so simple. All I have to do is divine from what I know of you: are you the sort of man who would put the poison into his own goblet or his enemy's? Now, a clever man would put the poison into his own goblet, because he would know that only a great fool would reach for what he was given. I am not a great fool, so I can clearly not choose the wine in front of you. But you must have known I was not a great fool, you would have counted on it, so I can clearly not choose the wine in front of me.

If first-and-third in the majors is starting to emulate Little League/HS/college, then MLB teams should fully embrace the elaborate set pieces of their league brethren.

Bluffs and runners slowing down are no fun. Let's have the runner on first fall ass over elbows on his way to second. Or the have the catcher throw a dart to second that the pitcher intercepts. Or have the defense put on a short one-act play with the catcher airing it out, the pitcher ducking, the infielder diving for the wayward throw, only to have the ball be in the catcher's mitt the whole time (a la Little Big League).