Basically five things determine the winner of a baseball game:

1—Whether the pitcher chooses the right pitch to throw and throws it well

2—Whether the batter makes good swing decisions

3—Whether the batter who swings hits the ball well

4—Whether the defenders can corral that contact

5—Whether the baserunners can create extra offense

There have been, on average, 298 pitches per game this year, and (on average) 49 balls put in play. That means 84 percent of the game doesn’t get past the second item on that list.

We have a lot of ways we measure Nos. 3, 4 and 5, and Statcast & Pitching Ninja have opened up novel ways of appreciating No. 1. No. 2, though—the batter’s swing decisions—have been minimally analyzed, beyond a batter’s walk totals or chase rates. It’s pretty obvious when a batter chases a pitch way outside the strike zone that he shouldn’t have done that, and it’s sometimes obvious enough to be frustrating when a batter takes a pitch down the middle. But when is the right time to swing, and who knows the right time to swing? Those details have gone largely unconsidered.

But last November, at Baseball Prospectus, Robert Orr introduced SEAGER, a new way of measuring hitters’ approach at the plate. Unlike basic plate discipline metrics—like chase rate—SElective AGgression Engagement Rate not only credits batters who don’t expand the zone, but also those who don’t let hittable pitches sail past. To steal a phrase from his article, SEAGER is a way of identifying hitters who showed “understanding of the zone, the count, and how to leverage those two things together to get pitches they could do damage on.”

SEAGER assigns a swing-decision value to every pitch, based on the count, the location of the pitch, the likelihood of a pitch in that location being called a strike, and the historical damage done by hitters who swung at pitchers in that location. This all goes into the “value” of a swing as compared to a take. The value can be positive (swinging at a pitch right down the middle on 0-2 is obviously a positive-value decision, compared to a take) or negative (chasing a pitch four feet outside on 3-0 is obviously a negative-value decision).

The SEAGER leaderboard from last year is awfully impressive:

Corey Seager

Bryce Harper

Ronald Acuña

Mike Trout

Jorge Soler

Aaron Judge

Emmanuel Rivera

Vladimir Guerrero

Rafael Devers

Juan Soto

Remember, these hitters aren’t at the top of the leaderboard because they hit the ball so hard. This is a leaderboard that measures only their decisions, not what happens after those decisions. These are the hitters made the best decisions. They also happen to have been among the most successful hitters in the game. Imagine that.

As I’ve watched games this year, SEAGER has never been far from my mind. I’ve become somewhat obsessed with asking, on each pitch, “was that a good swing/take?” Sometimes the answer is obvious. Often it’s not.

So I asked Robert Orr if he could give me the swing-decision values of every pitch in a bunch of games. He sent me a big spreadsheet from the first week of the season. I picked two games—April 1 and April 2, between the Rays and the Rangers—and watched them, comparing what happened to the swing-decision values of each pitch. Here’s what jumped out at me.

1. Hitters are really good at this.

We spend a lot of time mad at hitters for making bad swing decisions—and, in particular, chasing outside sliders that they couldn’t possibly hit—but those are the outliers that stick in our minds. Mostly, SEAGER indicates, hitters make really good decisions.

In the first game I watched, the Rangers—batting in the top of the first inning—made the “right” swing decision on each of the first 25 pitches! That’s not to say they never took a strike, or never chased a pitch that was slightly out of the strike zone, but that—according to SEAGER—they knew the appropriate time to take a strike, and even the appropriate time to swing at a pitch slightly out of the strike zone.

What made this more impressive to me is that, for a ton of pitches, the margin between a good and bad decision is pretty small. For example, here’s Marcus Semien, swinging at the first pitch of the game:

The first pitch of a game used to be a nearly automatic take. From 2009 to 2014, hitters swung at the first pitch of the game only 12 percent of the time. This year, the league has swung at it 30 percent of the time, and 45 percent of the time that the pitch has been in the strike zone. And you can see why: Semien nearly homers on the pitch. He knew what he was doing.

But it’s also a relatively close call. Swinging first pitch can lead to a home run, but it can also lead to a batter tapping a weak grounder for a one-pitch out. Taking a first-pitch strike would put him behind in the count but could also lead, in a roundabout way, to him getting walked in a drawn-out at-bat or homering when he gets a hanging two-strike breaking ball. (As it was, he did fall behind in the count… and then he did walk.) So the value of a swing here is clear but not overwhelming: The swing decision is worth about .013 runs. If Semien gets exactly this pitch in exactly this situation 75 times and takes it all 75 times, it would only cost him about one run.

And that’s a pretty unambiguous swing decision, SEAGER says. Here’s Evan Carter, taking the first pitch he saw, in the same inning:

The price for this take is an 0-1 count. But in Carter’s case, the pitch is too difficult to do damage on, so SEAGER prefers he sacrifice the strike—or, more than that, that the umpire would call it a ball, which would happen a fair amount of the time. So, smart decision, but the value of that wisdom is a mere .002 runs. Carter needs to make the right decision 500 times to produce a run. (Or, if he makes the wrong one 500 times, he’ll only cost himself one run.)

What really became clear from this exercise is how many pitches are so, so close to coin flip decisions. There are decisions that SEAGER estimates are worth as little as .00000001 runs against the alternative.

Ironically, the first “bad” decision that the Rangers made—on the 26th pitch of the game—was a first-pitch slider that Josh Jung took. SEAGER thought he should swing.

Jung’s swing-decision value was deemed negative, but it, too, was basically a coin flip—a .006-run decision against the alternative. When pitchers make great pitches—first-pitch fastballs on the black, for example—they’re making it very hard for hitters to get a big edge either way. And then the game often hinges on how well the catcher receives it, or what kind of mood the umpire is in. In this case, the umpire, unlike SEAGER, didn’t think that Jung should have swung. He called it a ball, even though it was in the broadcast-box strike zone. Jung went against SEAGER and ended up ahead in the count 1-0.

2. Some swing decisions swing some games.

Jung homered on the next pitch.

The game turned on that swing. The Rangers went up 3-0, and would end up winning 9-3. Jung could easily have taken the pitch, and accepted his 1-1 count. Nobody would have blinked. But that was a pitch to hit, and he didn’t let it get past him.

We see games turn on swings all the time. But what SEAGER helps us remember is that some number of games also turn on non-swings.

So, for example, the next day the Rangers were trailing 1-0. Wyatt Langford was batting with two outs and nobody on in the fourth inning. He let the first pitch go by:

SEAGER hated that take. Not only had Langford let a pitch go by that he could have done damage on, but he was now behind in the count. Predictably, with the pitcher ahead in the count, the next pitch Langford got was harder to hit. This wasn’t a pitch he was likely to hit out, and he fouled it off:

And, then, down 0-2, we see the predictable third act of this sequence. Zach Eflin tried to get Langford to chase, and Langford, having to protect, did:

It’s a sequence that shows up again and again in baseball:

Pitch one: Hittable, relatively high swing value, but taken for a strike

Pitch two: Less hittable, relatively low swing value, swung at for strike two

Pitch three: Unhittable, negative swing value, chased

In this sequence we tend to get mad at the final act—though Langford, at least, managed to stay alive with a foul ball—but SEAGER reminds us that it’s arguably the first swing decision, not the third one, that is the more avoidable mistake.

3. Always be swinging?

The Langford example—a power hitter taking a first-pitch meatball—is intuitive. What surprised me was how many borderline pitches, even pitches outside the rulebook strike zone, even in moderate hitter’s counts, SEAGER wanted hitters to swing at. This 1-0 pitch to Adolis García, for example:

That’s not a swing that I would have registered as a good decision. It turned a hitter’s count into an even count, and it’s not a pitch that you’d describe as “fat.” I’m certain that, if you watched these games like I did, you’d have about 10 pitches where you disagreed with SEAGER, and they would all be cases when SEAGER said “swing.”

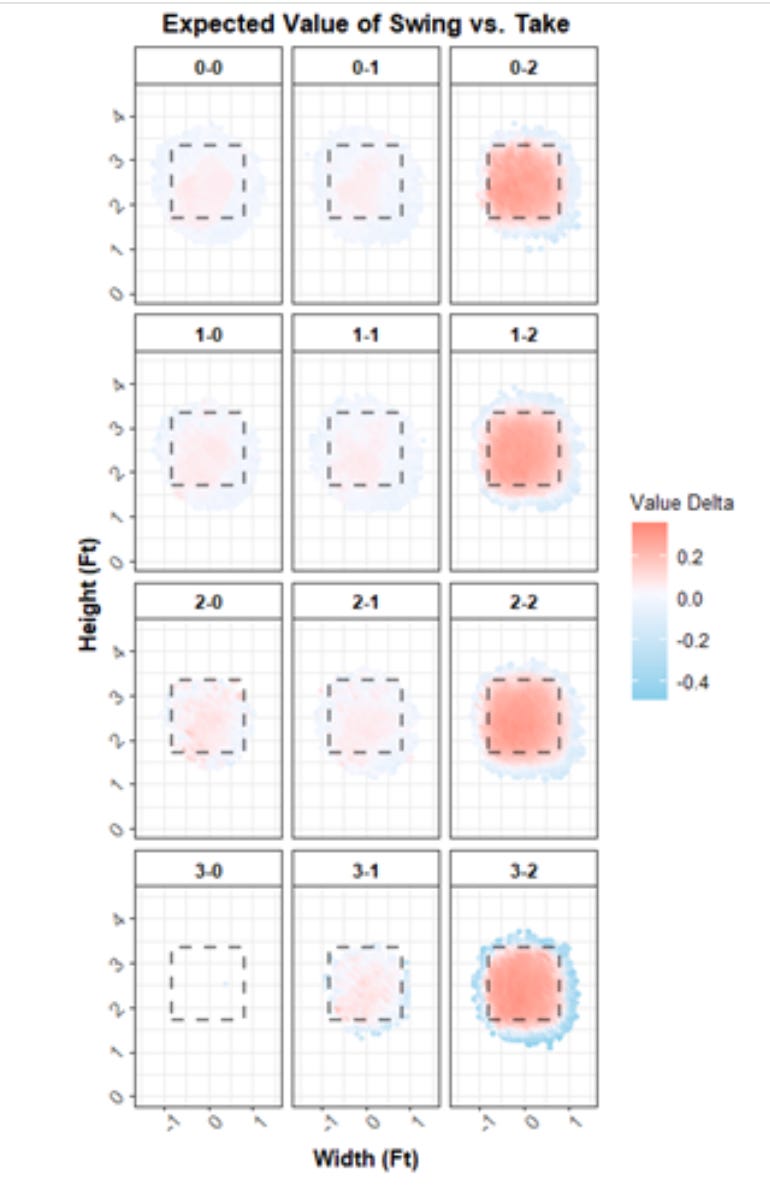

Orr published the swing-value zone charts for every count. Red means that SEAGER favors swings at pitches in those locations. Faint red means smaller benefits to swinging, but still more benefit than taking:

You can see, if you squint or zoom in, that almost anything in the strike zone is red in almost any count—and that there are even blurry red edges on the outside of the zone, too, just like where that Adolis García swing was. Part of this is that umpiring on the edges of the strike zone is pretty unpredictable, and those just-out-of-the-zone pitches really are something like 50/50 strikes. In the modern era, where there is essentially no such thing as a good two-strike hitter, SEAGER seems to have a thesis: Unless the batter is very close to getting his walk, a swing is generally better than almost any taken strike.

That said, there’s a limit to how far we can take this. SEAGER, at present, doesn’t consider the pitch type, or the batter’s strengths, or the pitcher’s strengths. Consider a hypothetical pitch location that half the league’s hitters can hit really well and half the league’s hitters can’t hit at all. If only the first group ever swings at it, then the data SEAGER relies on will show that it’s a good pitch to swing at, because most swings at it will have produced damage. But it’s obviously not a good pitch for the second group to swing at. And that’s why they don’t swing.

That is to say, a batter’s relationship to a pitch is unique. In individual cases, we can get frustrated when Langford takes one down the middle. But the alternate scenario—where he swings—might have turned out worse, and he might have known that. There’s quite possibly a reason that he took the pitch, which might be no more complicated than the pitch wasn’t for him.

Still, I’d be very surprised if some of these more precise details don’t get worked out in future drafts of this concept. In 10 years time, I’ll bet were talking about objective measures of swing decisions in real time, the way we now talk about pitchers’ tunneling, catchers’ framing, and expected batting averages on balls in play. Remember: 84 percent of baseball never gets past the batter’s swing decision. I found it absolutely entrancing to watch two games with real statistical insight into that 84 percent.

4. SEAGER explains it all?

Orr sent me the swing-values for 101 games. Curious, I devised the most absurdly simple way possible of seeing whether SEAGER predicts victory. I averaged each team’s swing decisions in each game. I looked at whether the team that made “better” swing decisions won the game. In this relatively small sample of 101 games, the team with better swing decisions went 59-42. That is, knowing nothing about these teams or their performances except whether they made good swing decisions that day, we can say they played like a 95-win team.

Maybe SEAGER’s predictability wouldn’t hold up in a larger sample, or with a more rigorous method of evaluating it on a team/game level, but I came away from my two-game experience even more excited about the possibilities of this framework. The concept behind SEAGER—that swing decisions themselves are the core component of offense, and that there is something close to a “correct” decision for every pitch—makes the static center field camera view of baseball richer with meaning.

The Rangers won the first game I watched, 9-3. According to SEAGER, they also made better swing decisions that day. And according to SEAGER, the swing decisions flipped in the second game, with the Rays making better decisions in aggregate—and winning the game, 5-2. The final out came on a first-pitch fastball that Pete Fairbanks threw to Leody Taveras, who was representing the tying run. Taveras flied out,

but it was the right time to swing.

Is it an exaggeration to say that SEAGER is the most significant stat created in the last few years? I'm thinking in terms of how much it explains about the result of a game and how big of a gap it fills. I want to say it's the most important new stat since the initial set of Statcast stats were introduced.

how does all of this jive with Eno Sarris' notion that for almost everyone except Barry, swinging is a negative? https://theathletic.com/3292610/2022/05/05/mlb-plate-discipline/