Discover more from Pebble Hunting

Installment 6: “Clem Labine died yesterday. It was his unparalleled success against Musial, an otherwise notorious Dodger-killer, that Labine maintained was his proudest accomplishment. He retired Stan the Man an incredible 49 consecutive times.”

. –New York Daily News, 2007

1.

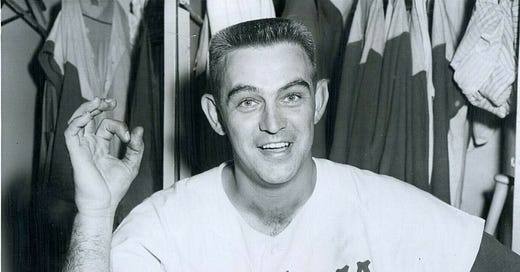

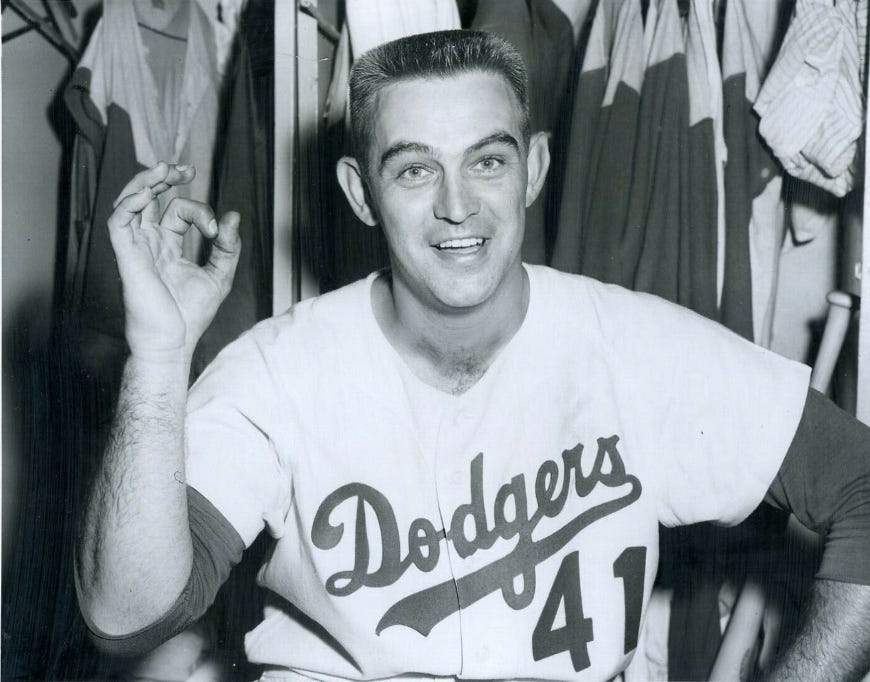

In 1950, Stan Musial won the fourth of his seven batting titles, and Clem Labine made his major league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Over the next 13 years, as they faced each other dozens of times, Musial would be the National League’s best left-handed hitter, while Labine would find a sturdy role as one of the league’s better right-handed relievers. He—Labine—was an All-Star twice, and for a time he held the Dodgers’ career record for pitching appearances. A rival manager was asked which pitcher he would take if he could have any pitcher in the league and the manager, caught up in the relief-pitcher fervor of the 1950s, named our guy. Labine also made two brilliant starts that were as close as they could possibly be to baseball immortality: He threw a shutout in Game 2 of the 1951 playoff between the Giants and the Dodgers, the game before Bobby Thomson’s famous home run. And he threw a 10-inning shutout to beat the Yankees in Game 6 of the 1956 World Series, the game after Don Larsen’s perfect game.

But his greatest thrill, he was quoted as saying, was his success against Musial. “Relying on a wicked curve ball and sinker”—according to his Associated Press obituary—“he had uncanny success against Stan Musial, retiring the Hall of Famer 49 straight times.”

You can understand why that would be a player’s biggest thrill. A crucial draw of playing in the major leagues, at the highest level, instead of simply staying home and dominating a Sunday league is the opportunity to test oneself against the best. That’s what the back of a baseball card confirms: This player, a very good athlete, was tested against the very best who were alive when he was, and here is how he measured up. Stan Musial is that idea taken all the way: Forget the marginal players, the fringe players, the too-young and too-old players. If this is supposed to be a test, let’s get to it: Labine was tested repeatedly by the very best hitter who had ever played in the National League.

Based on their respective overall stats, Labine, in one matchup against Musial, should have had around a 61 percent chance of getting Stan out. He’d have about a 1-in-100 chance of winning 10 matchups in a row. The odds of an 0-for-25—only halfway to 49—would be 200,000 to 1. The odds of an 0-for-48—not even an 0-for-49, but a mere 0-for-48!—would be about 20 billion to one. To get Musial out 49 times in a row, in other words, would require a truly unprecedented level of real, genuine, undeniable ownage. Such results based on random chance, or Labine’s good luck, or a slight edge, would be practically impossible.

In fact, though, it wasn’t just practically impossible for Labine to retire Musial 49 times in a row. It was impossible. He only faced Musial 48 times. That’s the first sign that something is fishy about this, the most preposterous fun fact in baseball history.

Stan Musial batted against Clem Labine 48 times, walked in six of them, and went 10-for-42 in the rest. He homered, tripled, doubled, grounded into two double plays. The record is pretty clear. So where did this 0-for-49 nonsense come from?

We already know it was there when he died in 2007—it was in that Associated Press obituary, and in the lead of the obituary written for the New York Daily News, too. It wasn’t in his Sports Illustrated obituary, an oversight that was corrected by a subsequent letter to the editor from “a loyal Brooklyn Dodgers fan”: “I mourn the loss of Clem Labine, a clutch pitcher who was underappreciated. One of his more unbelievable stats: He retired Stan Musial [etc and so on].” It was in his biography when he was inducted into the American-French Genealogical Society Hall of Fame: “Over the course of his career in Brooklyn, Clem retired Dodger-killer Stan Musial 49 consecutive times.” That was in 2005.

We can go back and back, finding scattered references to the Labine/Musial achievement, until we finally get to this passage in The Boys Of Summer (1972), Roger Kahn’s seminal past-and-present look at the 1950s Dodgers: “Do you know that I got Stan Musial out forty-nine times in a row? Somebody counted and told me. I’d curve him and jam him with the sinker.” That’s Labine speaking. According to Kahn, at least. Either Labine said it or Kahn invented it, and then it got repeated over and over.

2.

Just after Labine died in 2007, Richard Elliott wrote a book called Clem Labine: “Always A Dodger.” Elliott had grown up in Labine’s Woonsocket, Rhode Island orbit. Richard’s dad was pals with the pitcher, and Labine worked in the Elliott family business after he retired from baseball. The author and Labine were close up to Labine’s death.

“Clem always laughed at it, that absurd myth that Musial never hit him,” Elliott wrote in Always a Dodger. “About eight months before his passing, Clem and I were dining at his home and the topic came up again; that time, because my young son Jason had heard the Musial rumor at his school and had asked Clem if it were true."

According to Elliott, Labine told the boy,

I have absolutely no idea how that darn legend got started, Jason. Stan got a bunch of hits off me, but once that silly statistic popped out of thin air, it took on its own life. I think it all began when Roger Kahn brought up my pitching stats in our interview for the Boys of Summer, and then he misquoted my responses. Maybe that's what writers do, try to make things more dramatic. That's what Dick Young did all the time. He built a career on exaggeration and hyperbole. Dick never felt constrained by the facts and apparently, Roger could stretch 'em too. But zero for forty-nine as it's now reported? As Kahn says I claimed? That's BS. I remember getting Stan out a lot, maybe most of the time, but he hit his share. He didn't clobber me like Hank Aaron did, but he hit his share. I think what is true as I remember is that Stanley had trouble with my curve and my sinker, so I stuck with those two pitches and found some success. But zero for forty-nine? Stan Musial? Pure BS! No one could have done that to Musial! No one! No one ever came close to doing that!

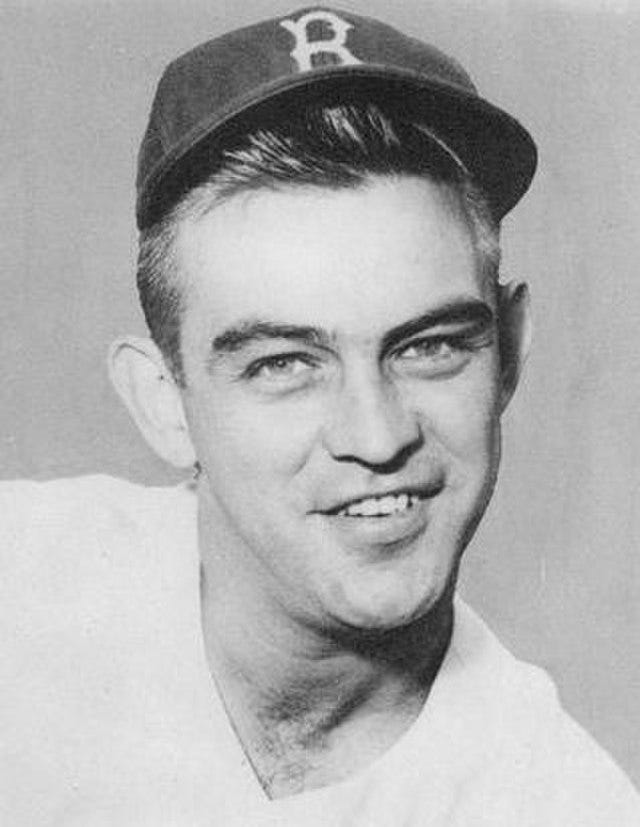

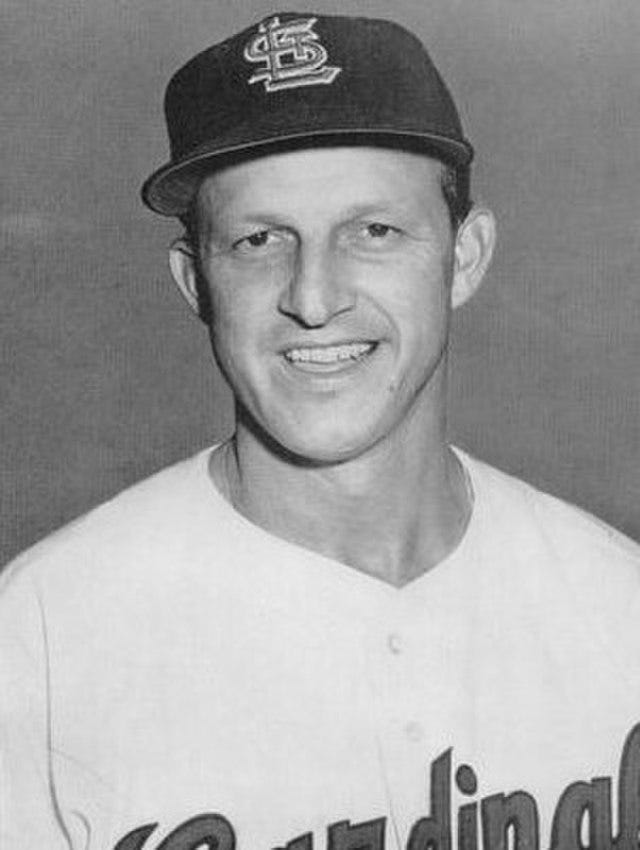

There is, in the 0-for-49 story, a little seed of truth. Musial really did struggle against Labine, and Labine’s success against him really was talked about frequently, not just by Labine—who once said his fondest moment was entering a game with bases loaded and retiring Alvin Dark, Musial and Red Schoendienst with high curveballs to escape untouched— but also by Musial. In a 1963 article, when he was asked who the toughest pitchers were for him, Musial replied:

Ken Raffensberger was the toughest for me. He threw slow and easy and I found myself trying to kill the ball. Johnny VanderMeer and Ewell Blackwell were tough and so were a couple of relief pitchers, Clem Labine and Bill Werle.

In 1964, he repeated the list, dropping Blackwell and Werle and adding Curt Simmons to the others. In 1975, Musial listed VanderMeer, Raffensberger and Labine. In 1976, his biographer Bob Broeg wrote that “Musial always regarded Labine as the most troublesome right-handed pitcher he ever faced.” And in 1993, “when someone asked him what pitcher gave him trouble on the Dodgers, Musial responded like he was citing facts from a textbook. ‘Clem Labine. He had a good sinker, a quick wrinkle. I didn’t have much trouble with Drysdale or Koufax.’”

Musial was right about Labine: At .238/.333/.381, Labine held Musial to a lower OPS (minimum 40 PA) than all but six other pitchers. Koufax (.342/.432/.553) and Drysdale (.324/.360/.427) didn’t give him much trouble, but Labine did. Labine didn’t get him out 49 times in a row; at one point, he did get him out 16 times in a row.

So how did that seed of truth grow into 0-for-49? There are three possibilities, if we parse Labine’s own words (or words attributed to him):

Possibility 1: Somebody told Labine wrong facts, and Labine passed them along in good faith.

Remember the wording in The Boys of Summer: “Do you know that I got Stan Musial out forty-nine times in a row? Somebody counted and told me.” It’s slightly hard to believe that Labine would so willingly believe that he had historic levels of ownage on Musial, considering he intentionally walked Stan Musial four times. But my own gullible tendency is to believe people are telling the truth, which means both that I believe Labine is telling the truth and I can relate to him believing whoever told him they counted.

Possibility 2: Roger Kahn made it up.

This is certainly the position of Elliott’s biography, which continues to scold Kahn and Young and other sportswriters for being story-inflators.

Notably, The Boys of Summer’s fame and influence as a book starts with its innovative literary structure. The first half comprises Kahn’s memories of being a young Dodger fan and sportswriter, written by a now-older man revisiting the gauzy nostalgia of his more impressionable youth. The second half deconstructs that nostalgia, visiting each retired Dodger two decades later and finding the beating hearts, aging flesh and morose second- and third-acts of real life. Labine is the first player that Kahn the author visits, and Labine’s story—as Kahn tells it—is one of regret, that he missed seeing his children grow up because he was so devoted to his baseball career. Kahn is contrasting the idea of Legend vs. Reality, and Labine’s story of getting Musial 49 times in a row is the very first baseball memory mentioned in the book’s second half. It works, in a way, as a metaexample of the myths we tell ourselves. One could easily imagine Kahn the litterateur hoping that the reader would recognize the unrealistic lie immediately and credit it to aging athlete’s mental state.

Anyway, Labine (as quoted by his friend Elliott) definitely pins this whole thing on Kahn, first describing it ambiguously as a misquote—which could be an accident—but then going harder, accusing Kahn of deliberate exaggeration to “make things more dramatic.”

Possibility 3: Labine made it up, to Kahn.

In Always A Dodger, Elliott writes: “Be assured, the culprit was not Clem Labine. I knew him my entire life, and you can trust me. Lying was anathema to him. Clem never maintained that fantasy as his proudest accomplishment, never maintained it at all, not to Kahn or anyone else.” But a few years after Kahn’s book, a different reporter who visited Labine again quoted him making this claim: “What was the greatest thrill of your career? ‘It wasn't a single thing,’ said Labine. ‘You see, Stan Musial never made a hit off me.’” This second instance makes it somewhere harder to square the idea of honest Clem Labine who never got it wrong.

Of the three, the first scans as the most realistic to me—except that Labine explicitly denied that that’s how it went, according to his friend Elliott’s book. And the unresolved would still be how Labine (and Kahn) could have believed something so preposterous. On the other hand, I believed it when I first saw. I went, Whoa.

3.

In 1965, Bob Uecker batted 15 times against Sandy Koufax and had six hits. Not bad! That’s a .400 batting average by a famously light-hitting catcher against an all-time ace, who was having (by some measures) the best season of his career.

Twenty-five years later Tim McCarver wrote an essay about his friend Uecker in a book called Cult Baseball Players:

Ironically, when we opened the season in Los Angeles against Sandy Koufax, baseball’s dominant lefty, I found myself on the bench cheering as my new backup got the coveted opening-day assignment. I’d been promised I’d play every day, but who could argue with [the manager] Keane for starting Uecker: for some reason, Koufax was one of the few guys Bob could hit with consistency. As a matter of fact, Ueck’s lifetime average against Sandy would be over .400, more than twice what he hit against all other pitchers, and he clubbed 2 of his 14 career homers off him. Who could figure it?

Well, nobody could. It wasn’t any truer than Labine’s 0-for-49 against Musial. Uecker hit .184 against Koufax in 41 plate appearances in his career. He hit one homer, not two. And up to the point McCarver’s story took place—opening day, 1964, the first Cardinals game after Musial’s retirement—Uecker had faced Koufax only once, and grounded out. As his manager Keane explained at the time, Uecker got the start over McCarver because Uecker was right-handed and Koufax was left-handed. One basic fact—Bob Uecker once hit .400 against Sandy Koufax in a season—was true, but in time the storyteller lost track of where it started and ended.

Why is baseball history filled with stories like these—filled, it sometimes seems, exclusively with stories like these? There are two possibilities, two ways of visualizing how our stories warp with age. One is entropy. Bodies of facts can hold together for a while, but over time they slowly break apart, as all bodies do. The stories we tell become impenetrably disordered. Consider the list of pitchers (from earlier in this article) that Stan Musial named as the toughest for him to hit. Against each of those non-Labine pitchers, Musial hit:

.325/.361/.545 (in 203 PA) against Raffensberger

.267/.347/.522 (in 103 PA) against VanderMeer

.380/.421/.549 (in 76 PA) against Blackwell

.179/.258/.214 (in 31 PA) against Werle

.374/.438/.561 (in 138 PA) against Simmons

Of the five non-Labine pitchers that a post-retirement Musial publicly credited with dominating him there were four pitchers he absolutely obliterated and Werle. Strangely, Musial never even mentioned Sam Jones, who was by far the most successful pitcher against him, holding the Man to a .122/.218/.143 line in 55 plate appearances. Musial’s memory here is either wildly idiosyncratic or atrocious.

That seems like entropy.

Labine’s fond memory of retiring Dark, Musial and Schoendienst with the bases loaded, which we mentioned earlier in this piece, and which he recounted to a reporter in 1988, never happened. Something like it must have, but never those batters, never that scenario, and never that sequence.

Maybe entropy.

Or maybe possibility number two, the natural selection theory. This one goes: In the story environment, the anecdote’s biological imperative is simply to survive. So stories are constantly escalating, even in our own minds when we tell them to ourselves. Each time we tell a story, we find the details we can improve on while still basically believing them (and having them be believed). Any mutations that benefit the story get reproduced. And the more a story is improved, the more likely it is to survive, until all that exists in the Big Book Of Anecdotes is exaggeration pushed to the brink of believability. Any that’s how, today, 60 years after both of these guys retired, you’re learning about Clem Labine’s (very real) success against one of the greatest of all-time. The truth had to get distorted into something preposterous, but through it some bit of that truth survived.

4.

If Labine was guilty of this tendency—and we’ll never know—he also seems to have been a target of it.

In 1985, a column by a United Press International baseball editor told a tale about Labine and Musial’s false fun fact. The editor explained that, every winter, the sports pages trawl for “Hot Stove” articles to fill space. “One common practice is to send a reporter to interview an old ballplayer and do a nostalgia piece. Such was the case a few years ago when a reporter was sent to interview Clem Labine.” (That interview presumably turned into this straightforward 1979 profile.) The editor continues:

“It wasn’t long before Labine realized the reporter didn’t know much about his career or baseball and decided to have some fun. The reporter finally asked the question for which Labine was waiting: ‘What was the greatest thrill of your career?’

“ ‘It wasn’t a single thing,’ Labine said. ‘You see, Stan Musial never made a hit off me. I think I got him out 67 consecutive times—and struck him out maybe 40 times.’ The reporter, of course, featured that angle in his story.

“The quote stopped the editor cold. Turning to an old-timer, he asked, ‘Is this possible?’

“ ‘It doesn’t seem possible,’ said the old-timer. ‘Let’s ask Musial.’”

The old-timer and the editor called Musial’s restaurant in St. Louis and asked the receptionist, who, fortunately, was standing “about 10 feet away” from Musial. She put the old-timer and the editor on hold and came back to say that

“…he says it isn’t true.”

"Would you ask Musial to come to the phone?" the editor said.

"He can't," she replied. "He's on the floor laughing."

Here’s the twist: The same editor appears to have written about this encounter four years earlier, in 1981. In the first telling, Musial had merely “chuckled,” but by 1985 the editor has Musial on the floor, incapacitated by laughter. In the first instance, Labine was said to have asserted the 0-for-49 fact, but by 1985 the editor has Labine claiming 0-for-67 with 40 strikeouts. In 1981, Labine was merely “trying to circulate” the fact, but in 1985 Labine was knowingly pranking the reporter.

In the original, 1981 telling, Musial gets on the phone to deliver a funny comeback:

"That's not right," said Musial. "But let me tell you this. Clem Labine was a mighty tough pitcher. I don't think my lifetime batting average against him was higher than .295."

(It was actually .238. A .295 batting average is very good for anybody other than Musial.)

In the 1985 telling, Musial also, finally, after pulling himself off the floor, gets on the phone to deliver a funny comeback:

“But listen, don't knock Labine. He was some tough pitcher. I doubt if my lifetime batting average against him was more than…”

Pick a number. Whatever number makes the story best. Normal ol’ reliever guy Clem Labine was the toughest pitcher Stan Musial ever faced, but that’s too good a story to waste. So, somewhere along the way, maybe somebody tried to do that story a favor. Maybe they told Clem Labine it was 49 straight outs. And maybe Clem Labine liked that so much that he kept telling it, whether or not it made sense. And Stan Musial liked that one so much that he flipped the punchline: Labine was such a tough pitcher that he held Musial not to a .238 average but .295. And a baseball editor liked that quote so much that he used it, and as the years passed, maybe he realized he, too, had wasted a perfectly good story by telling it straight. And so, in an article about an article that was about an article—in a 1985 retelling of the 1981 version of a 1979 Stan Musial response to a claim from a 1972 book about the 1950s Brooklyn Dodgers—the baseball editor seems to have added one final punch-up:

“I doubt if my lifetime batting average against him,” he now had Musial saying, “was more than .310.”

Which, whether Musial said it that way or not, was technically true.

Other installments in this series: Part 1, Fourth Place!; Part 2, Jack Barron’s Gigantic Exposé Of Obsolete Brain Wash; Part 3, Heroic & Tragic & Joyous & Juvenile; Part 4, Have You Heard The One About The Worst Pitching Staff Ever?; Part 5, They Boo Shortstops, Don’t They?; Part 6, Based On A True Story; Part 7, The Three Streaks of Joe, Ted and Bob; Part 8, The Last Good Pitch; Part 9, Team Sport; Part 10, Nothing Gets Weirder Than Hope.

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting

I'm writing about baseball & the good life. Contact at pebblehunting@gmail.com.

It's my observation that up to a generation or two ago, men were valued socially by how well they could tell stories. Think about it: With fewer things to do to pass the time, people spent more time at bars and social clubs. Being able to hold court was important, a sport unto itself. For this, telling exaggerations and outright lies were OK. It made the story better.

And at the time, it's not like anyone had the technology to fact-check all this stuff, anyway. How could anyone outside Elias or the MLB offices look up batter-pitcher splits from years past? Just tell the tale, fudge the numbers, keep it moving. It's more about the essence of the story, not the specific facts.

Sam is single-handedly deflating the "journalism back in the day was real journalism! with integrity!" hot air balloon with all his hole poking stories.