Discover more from Pebble Hunting

Can A Righty Reach McCovey Cove?

An investigation into one of the only baseball things that's never happened.

The emergence this year of Heliot Ramos—a right-handed hitter with oppo-bomb power—has rejuvenated Mike Krukow and Duane Kuiper’s interest in one of Oracle Park’s most interesting historical facts.

“We’ve never seen a ball hit into McCovey Cove—at any time, batting practice, game, it’s never been done—by a right-hander,” Krukow said on the Giants’ broadcast Tuesday. “And this guy could do it.

How realistic is a right-handed splash hit? Given the timespan observed—1,995 games, including the 2007 All-Star game—one could conclude it’s not realistic at all. But we are an optimistic people. We are always looking toward what can be. Unburdened by what has been, I think it’s a reasonable hope.

I looked up the most recent 50 splash hits, going back through the 2017 season and obviously all by left-handed hitters. (There’ve been 163 all-time.) I found the four that seemed most plausibly replicable by a right-handed batter, based on launch angle and distance. Distance is self-explanatory: It tells us how far the ball had to be hit to reach the water. Launch angle tells us how high it had to be hit to clear the various architectural impediments: The high brick wall, the SRO fan area, the chimneyesque columns at the back of Levi’s Landing, the pedestrian walkway below.

Then I looked at all the right-handed home runs hit in other parks this year—ignoring Coors Field—to see whether any would have been wet if hit identically in San Francisco. Here’s the score:

1. The low liner.

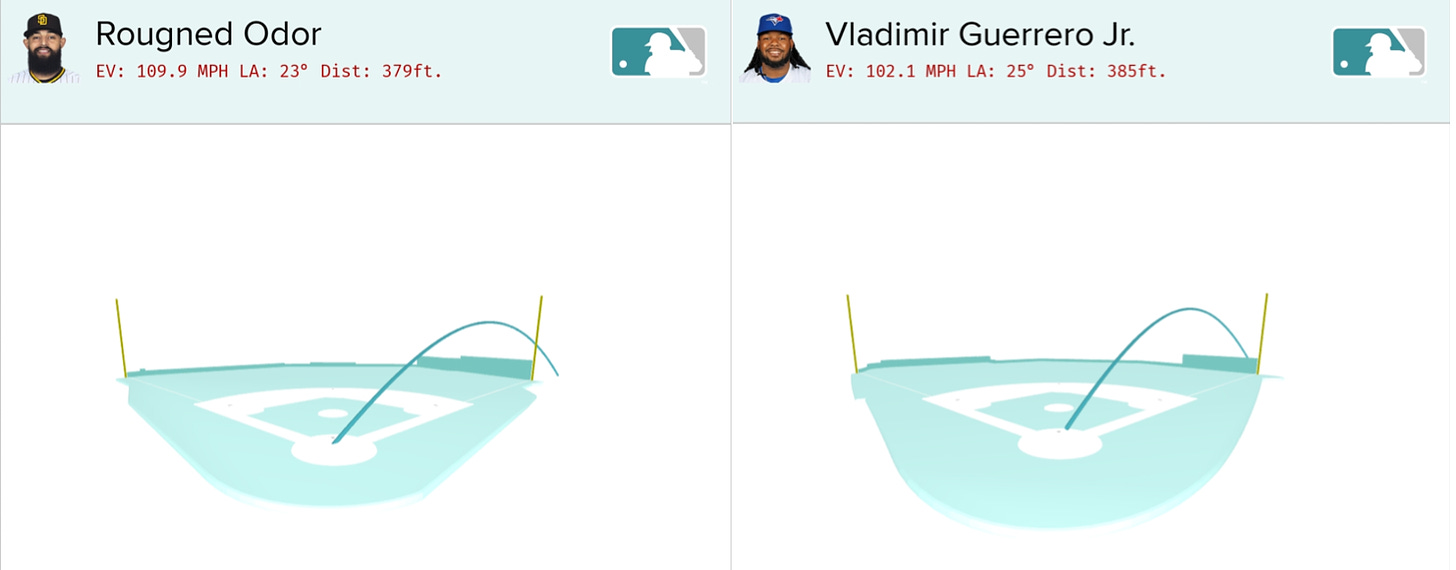

Lefty example: Rougned Odor, August 24, 2018; 23 degree launch angle, 379 feet.

There are very few similar right-handed homers. Most opposite-field line-drive homers are either 335 feet and they sneak over a low wall, or they’re 375 feet—but they’re hit out to the right-center-field gap, where players usually have a lot more opposite-field power. Unfortunately, those gappers won’t make it to the water. The further from the foul pole in San Francisco, the farther away the water is.

There is exactly one right-handed homer this year that looks like Odor’s, and it was hit by Vladimir Guerrero Jr. You can this home run’s trajectory coming as soon as the catcher sets up his target:

That’s 25 degrees and 385 feet, a bit farther than Odor’s ball and with plenty of clearance. Alas, though, it’s still not as close to the line as Odor’s ball:

So while I’d like to say yes to this one, I can’t be sure. That far into fair territory, it’s not conclusive that it would have reached the water.

2. The high liner.

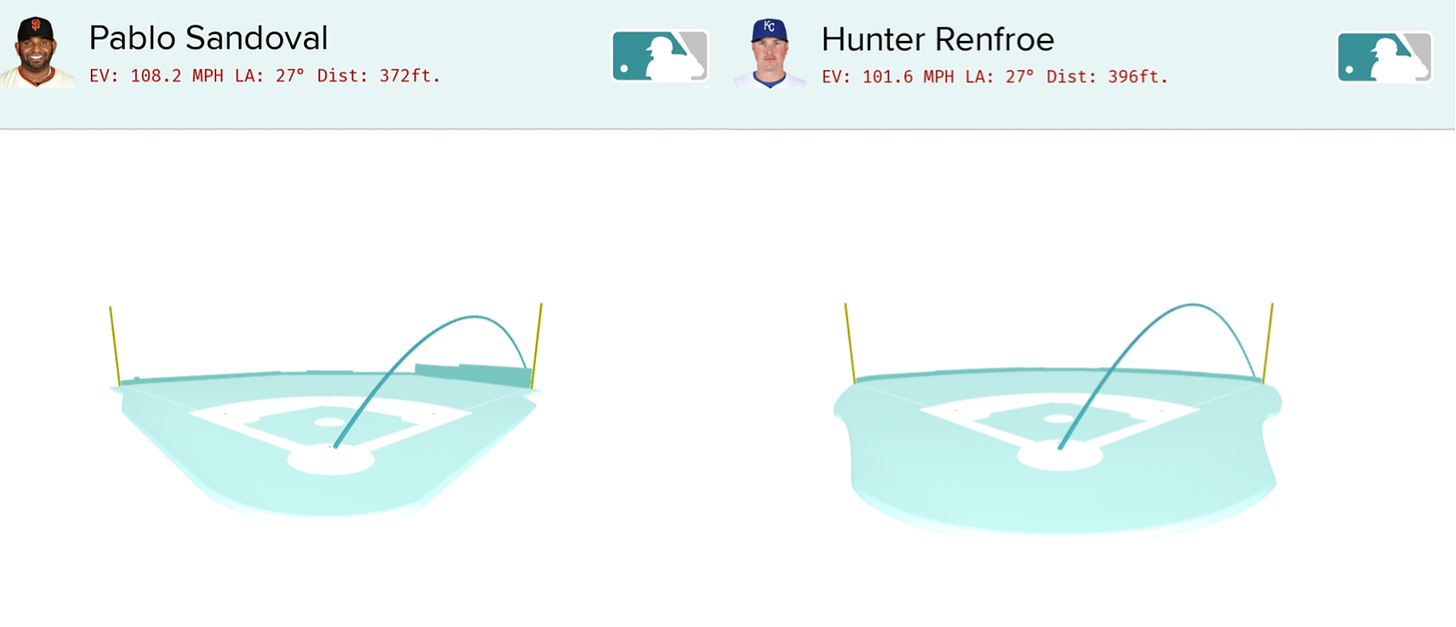

Lefty example: Pablo Sandoval, April 4, 2018; 27 degrees and 372 feet.

This one is a little higher than the Odor homer, so it doesn’t need to go quite as far to clear the stadium’s erected bits. But it’s still a tough combination for righties to mimic. I found only one really similar launch angle/distance swing from a righty this year. But it was way farther than Sandoval’s, 24 feet farther!

Further, unlike Guerrero’s home run, Renfroe’s cut about as direct a path to the nearest water as Sandoval’s ball did:

There are a few factors that contribute to a batted ball’s final distance. One is obviously exit velocity. Hunter Renfroe’s exit velocity (102 mph) was much lower than Sandoval’s (108 mph). But a ball hit the other way like this is more likely to get backspin (and extra carry) than a ball pulled with topspin on a low line. (You can see the topspin/backspin differences in each ball’s hump1 there.)

However, there are other factors we can’t precisely account for. The air was probably hotter that day in Kansas City than it usually is off the San Francisco Bay. The breeze that day in Kansas City might have been pushing the ball out to right field. And even minor variations within batches of baseballs can affect some balls’ distance by as much as dozens of feet. Point is: I can’t say conclusively that Renfroe could reliably hit a ball down 396 feet down the right-field line in San Francisco. But he did it in Kansas City, and that’s a compelling example.

However we want to factor in those unknown distance-effecting variables, I’m extremely confident, if not 100 percent certain, that Hunter Renfroe could hit a ball to McCovey Cove.

3. The high popup.

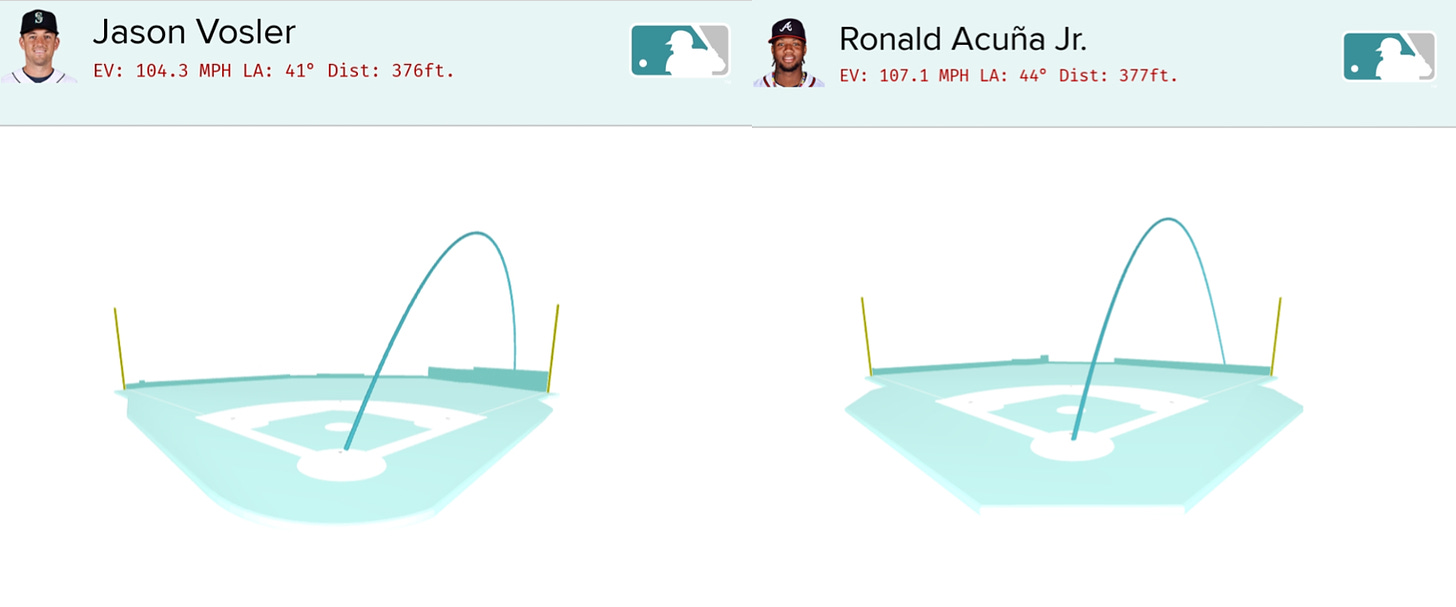

Lefty example: Jason Vosler, April 30, 2022; 41 degrees and 376 feet.

This is how you get one out that isn’t right down the line: You hit it high. This ball is probably 30 feet off the line, going right over the third or fourth archway,

a spray angle that opens up a lot more right-handed power potential.

On the other hand: It had to be extremely high—this was the 53rd highest home run hit in 2022—and that’s a really difficult angle for a right-hander to get to with power. In fact, no opposite-field homer this year has come close to mimicking this one’s specs. So I expanded my query back five years, to 2020. And really only one hitter came close. It was Ronald Acuña, and this is what it looked like:

Acuña launched that ball not 41 degrees but 44 degrees, and one foot farther than Vosler’s ball. Over the past five years, that is a singular home run. It is, alas, also farther from the foul pole than Vosler’s was, probably too far inland to get wet:

I hereby declare the high pop up home run into McCovey Cove not possible for a right-handed hitter.

4. The shortest possible distance homer.

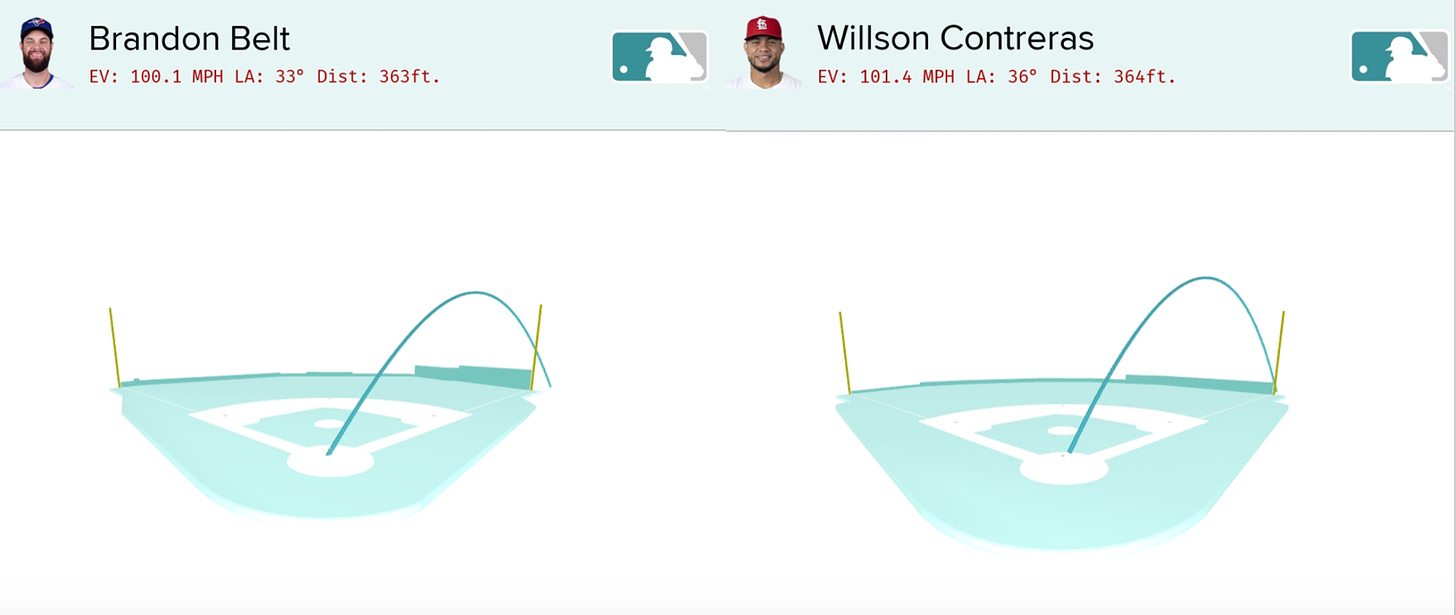

Lefty example: Brandon Belt, May 15, 2018; 33 degrees, 363 feet

This is the shortest home run to make it into the Cove since 2017, a combination of high and down the line and juuuuuuuust enough:

Arguably this is the best way, finding the shortest possible distance between two points. And, indeed, this combination of launch angle and distance is very attainable. A bunch of right-handed hitters this year have hit home runs of roughly this distance and roughly this launch angle to right field—and not just to “right field,” but actually toward the right field corner. Probably no example came closest to matching Belt than this one, from Willson Contreras. It’s one foot farther than Belt’s and hit at a 36 degree launch angle down the line:

Unfortunately, it doesn’t hug the line quite like Belt’s does, and it would therefore probably need more than the one extra foot of distance to make a splash.

I’m saying I do NOT think that Contreras’ ball specifically, hit identically in San Francisco, would have made it to the water. But this is a pretty unextraordinary home run from an fairly unextraordinary hitter. I think it’s fair to conclude that there are right-handed batters who could quite easily replicate this swing and go 10 or 20 feet farther with it, reaching the water.

To wrap the main body: We looked at four homers that went into the water. I’m confident that one of them (Sandoval’s) has been replicated by a superior home run of otherwise identical specifications this year. I’m confident that another (Belt’s) could quite easily be replicated by scores of right-handed batters, and that it’ll just take a convenient swing on a convenient pitch. I’m also optimistic that even Odor’s low liner could be replicated by great hitters, and that in broad strokes Vladimir Guerrero might be said to have done so this year. And I’m doubtful that one (Vosler’s) is possible for any right-hander.

There’s one last way I want to consider this question, though. The closest a right-handed hitter has ever come to McCovey Cove, according to Giants’ lore, came in the 2021 playoffs. Buster Posey hit a ball that clipped the top of the second chimney (and then bounced into the water, which doesn’t count for splash hit tallies). Would his ball have been in the water if the chimney hadn’t been there, or if Posey had hit it a foot in either direction?

This is that ball, which was hit 382 feet at a 30 degree launch angle:

So, you naturally wonder, has a lefty ever hit a ball into the cove with similar launch angle and distance similarly close to/far from the foul line? And the answer is… yes.

This is Joey Votto, 30 degrees and 384 feet. That’s two feet farther than Posey, but also—judging by the angles of the heads watching it go out—about 10 feet further off the line.

It was a splash hit. But a splash hit with maybe the smallest splash margin you’ll ever see:

What does Votto’s homer tell about Posey’s homer? Nothing we didn’t already know. Maybe it would have gone into the water. Maybe it wouldn’t have. It’s possible, but we’d have to see it to know for sure.

You might be thinking, “Sam, launch angle alone is a misleading clearance measure. If right-handers get more backspin to the opposite field than lefties do by pulling the ball, then their flies hit at similar launch angles will end up going a little bit higher and clear the right-field arcade more easily!” I agree. But since the conclusion of this article is “it could probably happen, these right-handers’ home runs show it,” I figured I’d be conservative with my assumptions. That’s why I’m not giving right-handers the extra benefit of the doubt based on their backspin.

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting

I'm writing about baseball & the good life. Contact at pebblehunting@gmail.com.

Without doing any digging, and purely hypothetically thinking, I wonder if Giancarlo Stanton stayed in the NL if this would’ve happened already. I know most of his huge HRs are pull-side, but the combination of him hitting low-lining missiles and his huge EVs make me wonder. Great article as always, Sam!

i can see oracle from my apartment three miles away up on a hill in SF - when i get my binoculars out, I can read the scoreboard (it was the first thing I did after finding out Mays died, and they already had a graphic up, despite no game going on at that time).

i think it's really cute that they have a camera in a place no one else would, specifically for cutting to the pedestrian walkway as a homer goes to right field to show if it's a splash hit or not. a bespoke solution.