Discover more from Pebble Hunting

Hello, and welcome back to part two of 10 Articles I’m Never Going To Write. Unless you consider 1,053 words about the best pitcher in baseball an “article,” in which case this newsletter post is a paradox. Either way, I’m soon to be free of five more topics.

6. Who Is The Best Pitcher In Baseball?

For most of the past 40 years, I never doubted that there was a best pitcher in baseball. There were periods when people would have disagreed over who it was—Gooden or Clemens, Maddux or Clemens, Pedro or Randy, Lincecum or Halladay, Kershaw or Verlander or Scherzer, with some Santana, Lee, Kluber and deGrom mixed in—but to understand that there WAS a best pitcher in baseball wasn’t just logic (somebody must be best), but a deeply felt reality. Watching Gooden, Clemens, Maddux, Johnson, Martinez, Santana, Lincecum, Kershaw, Scherzer always felt like standing under the world’s tallest skyscraper. You didn’t even need to know how tall the other skyscrapers were to look straight up and understand something powerful had happened.

A week or two into the 2023 season, I had absolutely no idea who the best pitcher in baseball was. And, furthermore, as far as I could tell neither did anybody else. There were strong pre-season cases—or, I guess I should say, muddled cases for—:

Justin Verlander, Sandy Alcántara, Gerrit Cole, Spencer Strider, Corbin Burnes, Jacob deGrom, Zac Gallen.

And MLB Network had Carlos Rodón and Max Scherzer 3 & 4 (with Strider and Cole off their top 10 entirely) in their season preview.

And you could have argued Shane Bieber and Zack Wheeler over some of those names, that with two great months they’d be the right answer.

And Max Fried, by recent years’ run prevention alone, might actually have been the right answer, even though nobody would have stood up for him. And three weeks into the season it seemed like the answer had just that fast actually become Shane McClanahan.

If you’d asked a survey of 100 active baseball fans, I don’t think any of those pitchers would have gotten 15 votes, maybe not 10. The only pitcher who might have was probably Shohei Ohtani, and he was obviously not the right answer.

So I was going to write this article about the lack of a Best Pitcher In Baseball, but then I got distracted. As the season went on, most of those pitchers got worse or fell out of the conversation. Alcántara’s and Rodón’s ERAs roughly doubled from the year before, deGrom had his shortest season yet, McClanahan’s season started to crater and eventually he had Tommy John surgery, Bieber’s strikeout rate fell well below the league’s average. Verlander and Scherzer were fine but suddenly looked obviously too old for the title. Burnes’ peripherals dropped off. Strider in ‘23 had the stuff and the strikeouts and the FIP… and the fourth best ERA in his own rotation. This, arguably, was the point all along: None of those pitchers had the combination of track record, peripherals, age, health, command, inevitability that the best pitcher in baseball is supposed to have. Predictably, they fluctuated and/or declined and/or regressed. (Wheeler and Gallen were both very good—but more like Kevin Appier good than Greg Maddux good. Fried was too hurt.)

Meanwhile, a guy who was actually winning the Cy Young award—Blake Snell—for the second time!—with a 1.18 ERA in his final 22 starts!—was nevertheless so unconvincing in the role of Best Pitcher In Baseball that he might end up signing a pillow contract this offseason. I say might, because the season starts in eight days and he still doesn’t even have that, as teams look somewhat skeptically at a pitcher who has mastered the modern skill set of big stuff in short outings. Other than Snell, nobody else particularly rose up out of the field last year.

So I kept thinking I was going to write this piece, because it felt like it was getting more interesting by the week. Except that Gerrit Cole ruined it. He won the AL Cy Young, he won the ERA title, he led the league in WAR, and—as PECOTA’s pre-season favorite going into 2023—he had a convincing track record behind him. Statistically, Cole is a very weak Best Pitcher In Baseball, by historical standards. But if you had done a 100-fans survey last week I bet he’d have gotten 50 or more votes. There was no story left. Cole was not a particularly interesting answer, but he was convincing enough that there also wasn’t much room for an interesting debate.

Although now, as I write this, comes news that Cole is getting multiple opinions on an MRI of his elbow. So we wait to find out whether he’ll be pitching at all.

I used to have this quote on my article to-do list—it’s from Tom Glavine in Sports Illustrated before the 1997 season:

“What you’re going to see is relief pitchers getting more and more decisions,” Glavine says. “You’re going to see pitchers with ERAs under four considered to be having a great year. And because teams are so careful about protecting young pitchers as they come through the minors, you’re going to see pitchers who can’t work beyond 100 pitches in a game, which means they’ll be done after four or five innings. What happens then?”

One thing that happens then (i.e. now) might be what I just laid out above: We might find it harder to have a best pitcher in baseball going forward. I’m only cautiously suggesting it, because Clayton Kershaw’s unambiguous reign wasn’t long ago and because Jacob deGrom would have obliterated this discussion by staying healthy in recent years. But part of what happens in modern ball is that starting pitchers’ seasons are all pretty much small samples—120 to 180 innings for most starters, even with good health. That means the “best” pitcher in any given year is a lot more likely to be a fluke, and it means the actual best pitcher is more prone to fluctuation the obscures his reliability. You could argue that’s what happened to Gerrit Cole in his so-so 2022, and what made MLB Network leave him out of their top 10 pitchers before last season. You could argue it’s what happened to Spencer Strider’s ERA last year, and keeps him from being an answer here today. You could argue it’s why people find it hard to believe in Blake Snell, and you could argue it’s why they shouldn’t.

And then they get hurt. It’s like modern pitchers come and go faster than their sample sizes can catch up to them.

7. Lost Ball/Scary Neighbor

Some months ago, I had a great email exchange with Brian Baynes, who recently published an English translation of Inoue Kazuo’s classic 1948 manga, Bat Kid. “Until Bat Kid trotted onto the field, there appears to have been no extended, multi-page manga serial specifically about the fun and excitement of Japan’s adopted national pastime,” wrote Ryan Holmberg, in an essay that accompanied the new English translation. “Given how many baseball manga there have been since, and how important they have been to Japanese culture and sports—many pro ballplayers in Japan can name their favorite baseball manga at the drop of a hat—this is far from a trivial first.”

Bat Kid is about a kid who wants to play baseball but isn’t any good at it, though he still finds different ways to enjoy the game. In one game, he watches a fly ball sail over his head and into a neighbor’s yard. “The man who lives there is a monster,” a teammate says. “He’s never returned any of our balls. Not a one! Forget it, Bat. Just leave it!”

Bat Kid goes anyway.

This is basically the plot of The Sandlot: A baseball gets lost in the scary neighbor’s yard. The kids muster up the courage to retrieve it, and not only get the ball back but find out that the scary neighbor isn’t scary, the mean dog isn’t mean, and the lost baseball isn’t alone: They get all the baseballs they ever lost back. “Now we can play forever,” one of the Sandlot kids says.

Which also happens in Bat Kid:

To settle myself at night, I listen to a podcast hosted by three Jungian analysts who break down fairy tales and dreams. When particular tropes begin to show up repeatedly, as I understand it, they probably represent something universal in the human psyche, called the collective unconscious. So what does the lost ball/scary yard say about us as humans? My non-Jungian guess is that the ball represents something like life itself—you can’t play the game without it, its movement is the very stuff and breath of animacy, it is easily lost and—we fear—once lost can be impossible to retrieve. The scary neighbor represents the other side of death, and Bat Kid (and the Sandlot kids) must conquer this underworld in order to retrieve the ball/life. When they do, they discover that life is more abundant than they feared—suggesting at the least that our fear of death is an exaggerated terror and at most that our souls are sturdier than death itself.

Anyway, for a while I thought I’d dig into other examples of lost ball/scary yard stories (or even lost ball/pit of snakes stories), and find some Jungian analysts to explain the significance of them to me. If you’re a Jungian analyst, feel free to reply to this email and tell me.

And if comics and baseball is part of your overlap: Here’s the link to Bat Kid, translated and for sale.

8. Ump Cam Makes Hitting Look Too Easy

One of the themes of the pitch-GIF internet over the years has been that it’s a miracle anybody ever gets a hit, at least against good pitches. We used to have only rudimentary clues that such pitches were unhittable, primarily: Velocity readings; extreme tumbling or sweeping movement observed from the center field cameras; and, most especially, the hitters’ reactions and awkward swings. When I used to write my The Best Pitches Thrown This Week column at Baseball Prospectus, it might as well have been called The Worst Swings Swinged This Week.

In recent years, new tools for identifying unhittable pitches have emerged: “Inches of run,” for example, means a fastball’s movement needn’t be merely observed by our amateur eyes but can be quantified. Pitch tunneling—the way a slider and a fastball might look exactly the same up to the point a batter must decide to swing, before verging off course from each other—can be demonstrated through pitch overlays. And, as of this year, some major league broadcasts have started using Ump Cam, as some college broadcasts had for a few years. When pitch-appreciation titan Pitching Ninja tweets a video of a nasty pitch captured by ump cam, he will reliably get lots of replies along the lines of: “What in the world are you supposed to do with this pitch?” and “I’m scared” and “Good luck with this.”

Those are real replies to a pitch by Paul Skenes, the first overall pick in last year’s draft, and for all I know, they’re accurate: It might be an incredible pitch. The problem is that, to me, and this is almost always true, the Ump Cam makes it look pretty hittable. Just look!

Now, nobody you’ve ever known in real life could hit that pitch. But, in the dozens of times I’ve seen pitches on ump cams, I’ve consistently found that they look easier to hit than I know they are, and easier than good pitches usually look from the center field camera. I’m not totally sure why this is, but my theories:

1. The challenge that the ump cam seems to be presenting to us, the viewer is: Can you even see this pitch? Can you even track it? And the answer is “yes, quite easily.” The ball’s entire journey takes place right in front of us, perfectly centered. I don’t mean to brag, but these pitches never even leave my sight. I’m on ‘em, the whole way. I’d go so far as to say I never even find myself surprised by where they end up.

I think this is kind of obvious, but what makes hitting hard isn’t actually visible. The hard parts are swinging a big heavy bat fast enough to hit the pitch, and putting that big heavy bat right where the ball is, and making a decision of whether to swing (and where to swing) in the first 20 percent of the ball’s journey. The ump cam gives us the illusion of being In The Game, but it’s only the illusion. We’re still just watching, which from this angle remains easy.

2. But then why would pitches look harder from the center field camera, when that camera also removes us from all the things (holding the bat, needing to actually make a swing decision) that make hitting hard? Simply, that we have watched tens of thousands of those pitches, and so we have a mental dictionary of good pitches and the bad swings they’ve produced. We’re not actually fooled by pitches from the center field camera, but we know what a good pitch looks like because we’ve seen, through thousands of trials, what effective pitches look like. At least until we’ve seen the Ump Cam several thousand times, we won’t have that visual vocabulary in our brains. We might pretend to. But, I think, personally, that if we’re honest with ourselves these ump cam pitches all look deceptively plain--almost plain enough that you could make the lethal mistake of thinking “I could probably hit that.” (This is especially the case when the pitch is getting blasted.)

3. I suspect it’s also easier to track the ball from the umpire’s view (and the catcher’s) than from the hitter’s. For the umpire and catcher, the ball is coming directly at their two eyes. For the batter, the ball is off-center and going past them; there’s a change in reference that the brain has to make. It’s not lined up with your two eyes (unless it is, in which case, YIKES.) I have a faint memory of seeing Edgar Martinez batting while wearing a helmet cam many years ago. My recollection is that, from that angle it really did look impossible to track a pitch and accurately foresee its ultimate location.

This article idea was under a separate article idea I had, called Take Parade. A parade of my takes. But I found that “ump cam makes pitches look too easy to hit” was my only take. I’m crossing both ideas off now.

9. Real Life Matt Christopher Dialogue

Reader John sent this to me:

I know you’ve got a lot of beats to cover. But have you ever considered tracking the times per season that players spontaneously turn into characters from a Matt Christopher book?

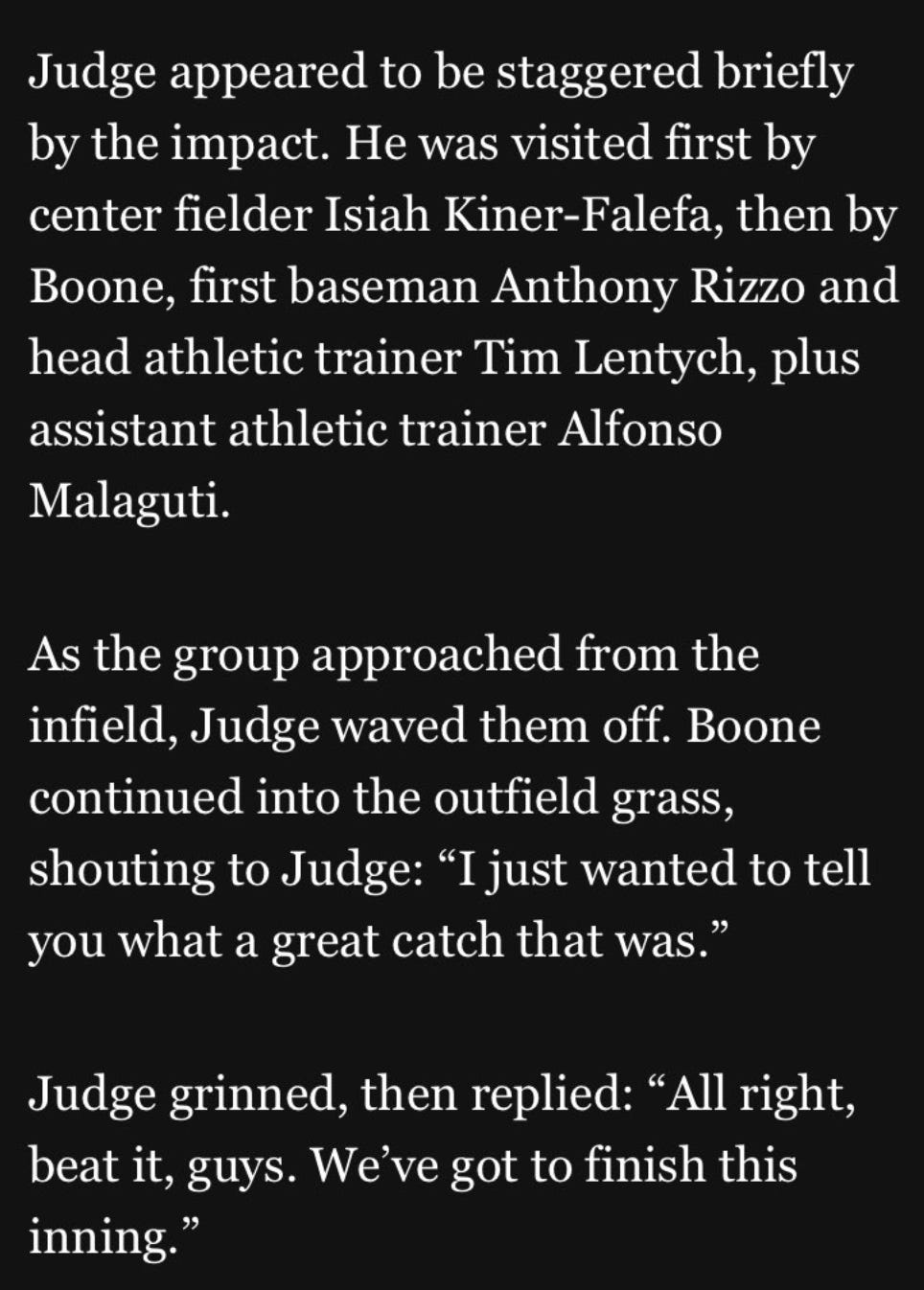

That is a GREAT article topic. Unfortunately, John’s example above was so good that, despite keeping an eye and ear out for the rest of the season, I couldn’t find even one more example that was nearly on the same level1.

Judge’s full quote: “I told him to get out of there, because (pitcher Michael) King is rolling right now, and I want to get out of this inning. They did their normal check, said great catch, and I said ‘let’s beat it guys, we’ve gotta finish this inning.’” I do think the “let’s” instead of “all right” diminishes the quote a bit, as far as vintage Matt Christopher dialogue flow goes.

10. Twins Pitching As A Certain Seacraft From Greek Philosophy

During the AL Division Series, Alex Rodriguez said this about the Twins:

You gotta give the Twins’ front office a lot of credit. They go from 30th in [pitching] strikeouts to no. 1. They were 30th for 11 years. They had a guy named Slowey pitch for them. In my career, I’ve never seen a pitching staff be 30th in strikeouts from ’11 to ’22, and this year they jump to number one! They’ve done it by trades, one each year.”

Now, that’s misleading phrasing. The Twins weren’t 30th every year from 2011 through 2022; they were 30th during the 12-year period that spans 2011-2022. In 2022, for example, they were 19th, so last year they jumped from 19th to 1st.

Still: it is true that for the first third of my ball-writing career, from 2011 through 2015, the Twins were last in baseball in strikeouts for five consecutive seasons, and perhaps no team had a competitive identity as clear as the Twins’ pitch-to-contact identity. They really did have a guy named Slowey. Also a guy named Correia. And a guy named Palfrey. A guy named Swarzak. Not sure why we’re naming guys.

And then finally they decided enough of that, and they started moving up the list until they reached the top of it last year. Even before Rodriguez mangled the fun fact, I had aspirations of writing about the Twins’ eight-year process of turning over an entire organizational identity, piece by piece.

But I never got excited enough by the idea to follow through with it, for two reasons:

It wasn’t a smooth enough trajectory. After they were 30th each year from 2011 through 2015, they were 28th in 2016 and then 29th in 2017. Why couldn’t they have gone from 30th to 29th to 28th? It would have made this a much better topic. They they went to 16th, and then 12th, and then because of the screwy sample-sizes of the 60-game season they actually were 5th in 2020. And then they dropped back to 23rd, then 19th, and suddenly no. 1 this year. It’s not a great trajectory for analyzing the supposed “one trade per year” explanation. There’s room for some fudging, but the Covid season blip in particular took too much potential out of it.

I couldn’t figure out a way to write the piece without mentioning the Ship of Theseus. I’m almost certain I’ve used up my allotted Ship of Theseus references, and if it turns out I have one left I’d rather save it for something else.

Still: The Twins led the majors in strikeouts last year, Crazy stuff!

***

As I noted in the first part of this series, it’s been a year since I launched this newsletter. People ask me how it’s been going, and I always struggle to answer as confidently as I should. I’m enjoying it so, so much. I feel creative again and I’m proud of the work and I’m incredibly gratified that when I declared I wanted to write for a living again so many people said “yes, we will make that possible.” I love the interactions with readers. The hardest part is not really knowing whether it’s actually working, because the measures of success that I was used to are gone: I don’t have an editor telling me a piece is good enough to run, nor telling me 600,000 people read it after it ran. Twitter/X is a ghost town, no longer the affirmation engine it used to be. So I stress a lot about that.

I was especially worried about the approach of this month, March 2024. Something like 70 percent of my subscribers signed up in the week I launched last year, many of them with annual subscriptions, which meant a lot was riding on the one-year auto renewal week. I was terrified I’d find out this wasn’t working. I worried about March 2024 coming for… about 10 months. But it came. And the drop rate was tiny. Well over 90 percent of last year’s annual subscribers re-upped. I feel incredible about that, and if you’re a free subscriber who is just not sure whether to pay for the second half of all of my posts, consider that an endorsement.

So, onward, hopefully with more confidence. I don’t have big changes planned, but I guess I’ll state one thing and ask for feedback on another. The one thing is—this isn’t a promise, but I strongly suspect that I’ll find a way back into podcasting at some point this year. I’ve got various ideas as far as format and topic, and with extra confidence I think I’m likely to go forward with one. Call it 80 percent confidence that by the summer I’ll be talking out loud.

The request for feedback is this: I don’t write a ton of posts, because the ones I write try to be comprehensive, and they take a lot of time to do well. But do you have a strong preference between more/shorter posts or less frequent/long posts? I know for some people it’s a burden to get lots of emails. I know for other people it’s a burden to read long emails. Given that you’re getting emails from me, which do you like more? It really might affect how I do this.

Finally, I want to say: Thank you. I hope you feel like you’re getting what you paid for. I want every month’s writing to be worth it. But also, know this: If I write for 20 more years, it’s all because you all made it possible for me to get back into this. Whatever I produce for the rest of my career, here, there or anywhere else, is the fruit of your support. I’m grateful, and I hope you’re happy.

In the same article as the Judge quote, Gerrit Cole did say this: “Gosh, what a blessing to have him on my team.” Which definitely sounds less like real ballplayer talk and more like bad book dialogue, just not a Matt Christopher book.

Subscribe to Pebble Hunting

I'm writing about baseball & the good life. Contact at pebblehunting@gmail.com.

Keep the long posts coming, please. Lots of people can write relatively short posts that stay interesting. I would enjoy your short posts as much as anyone, but really, I don't need more of those. Very few writers can handle the longer form the way you do, reaching conclusions that require a bunch of careful, precise refinements that play out in sequence. It's a rare joy to see what you come up with.

I mean this with all sincerity... as long as Sam Miller ends up in my inbox, I don't care if it's 100 words or 10,000. Thanks for year 1.