Almost all the good hitting seasons this year are in the American League. Shohei Ohtani—who seems like he’s on track to be the unanimous MVP in the NL—would be only sixth in the AL in WAR1. Meanwhile, the NL’s sixth-best WAR belongs to… Masyn Winn. Fine player having a fine season, but c’mon, he’s got a 108 OPS+. An MVP ballot of the AL’s top 10 players has produced, on average, 6.5 WAR; that’s basically Ohtani this year. The NL’s top 10 players have produced, on average, 4.9 WAR; that’s basically Dalton Varsho this year.

AL MVPs are on my mind because Grant Brisbee and I gabbed last week about why Bobby Witt Jr. vs. Aaron Judge wasn’t developing into an epic-MVP-race discourse, a la Trout/Cabrera 2012. At the time that Grant and I gabbed the two players were basically tied in WAR, yet, I argued, everybody knew Judge was going to win the award, probably in a landslide. Since then, Judge has hit seven homers in the seven games. Witt’s on pace to top Mike Trout’s career high in WAR, to produce more WAR than any infielder since 1927 Lou Gehrig—and I’m not sure he will get a single first-place MVP vote?

Today, it’s emails. You can always send me questions by replying directly to any newsletter post, or by emailing pebblehunting at g mail dot com.

1. MIKE ASKS!

Thought of you immediately upon seeing this footage! Wild!

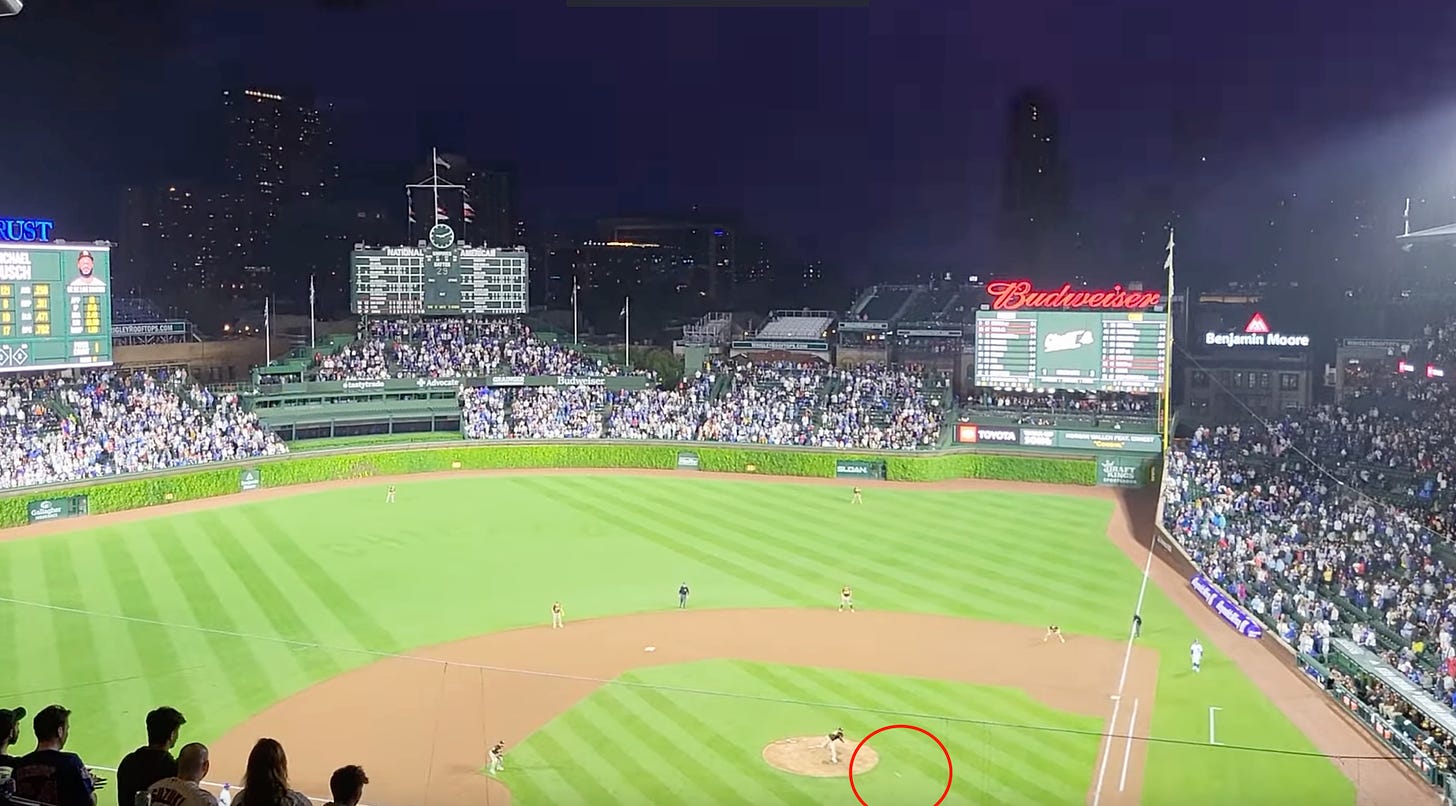

SM: That’s the Cubs’ Michael Busch hitting a walk-off homer a quarter-second after lightning strikes beyond right-field. Here is an exact moment the sky flashes, and the exact location of the baseball:

(Here’s a better view of the lightning (but worse view of everything else).)

That’s cool. Is it the coolest? Let’s say you, as the hitter, can pick any moment for lightning to strike on or around your walk-off home run. Let’s say the strike is a half-mile away, so the thunder will arrive 2 1/2 seconds after the flash. In that scenario I’d rank the lightning-timing options roughly so:

1. Exactly 2 1/2 seconds before the pitch arrives at the plate. We can go one of two directions with our symbolism: We can pick a moment when the lightning seems to cause the homer, or a moment when the homer seems to cause the lightning. This is the one option that arguably captures both: The lightning, coming just before the pitch, enchants the world/Busch’s bat; and Busch’s swing, power-boosted by this enchantment, creates the thunder with its impact.

2. Exact moment of contact. The bat carries the electric charge, and upon contact that energy fills the sky. Simple, elegant. The thunderclap—coming before the ball lands—might even still be audible, as the uncertain crowd wouldn’t have let out its full roar yet.

3. Two seconds after contact, precisely 2 1/2 seconds before the ball lands. Here the lightning is in the backdrop as the ball sails toward oblivion; a beautiful view. I’d like to say that a thunderstrike just as the ball lands would be extremely cool, too. But, realistically, the crowd would have already turnt up its full volume, and the thunder would probably be washed out. Still, worth a try.

4. Just as the ball lands. Symbolically, the game-winning ball carries the electricity in this one, and upon grounding it electrocutes the whole city.

5. While the ball is on its way to the plate. Creates a moment of disorientation—what was that?, are we in danger?, the hypothalamus racing ahead of the prefrontal cortex— that is then resolved by the cathartic home run swing a split-second later. Implies, as in the option ranked no. 1, that the lightning enchanted the bat or batter.

6. Just as the runner touches home plate. Game officially won at that moment, apocalypse rains down, world ends.

7. While batter is circling the bases and the camera cuts to his teammates celebrating in the dugout. If lightning is bright enough, the flash lights up the teammates, evoking the final home run trot in The Natural.

8, in some ballparks only. About one second after the ball lands, when the home team’s ballpark is shooting off fireworks (if it’s a ballpark that shoots off fireworks). Not totally sure this would play, but I think it’d be cool to think that the sky is trying to join in with the fireworks, like when you’re dancing around the house and your dog tries to be part of it.

9. As the runner is rounding third, exactly 2 1/2 seconds before he touches home. Timing it with the thunder. But probably nobody would actually hear the thunder. Too loud in that stadium.

10. Later that day.

2. EVERETT ASKS!

In our daily lineup rotisserie Fantasy league, deciding which fringey guys to start is a struggle. Today, I’m choosing between Ramos, Wood, Kwan, and Freidl for two spots.

I'm tired of this exercise being subjective, so I’ve created a model to help me decide:

[Lays out in several hundred words the five categories he ranks players on each day; details not important.]

I would love your feedback.

SM: I, too, have a personal model that I use when making draft or pickup decisions in my two-player fantasy league. It’s a ridiculous model. There are various formulas like (PA/580*(SLG-.330)*520)), and a column labeled “FrugPoints.”

You’ve got the right idea in creating your own personal decision-making metric. Fantasy baseball is about turning a game over which you have no control (other people playing baseball) into one in which you have some control. The whole point is to feel a sense of agency, which comes through in the decisions YOU make based on YOUR insights/expertise/philosophies of the world. So why blindly follow the Yahoo! player rankings or average-draft positions or conventional wisdom? Create your own secret sauce. It feels good to have one's own recipe. (This is why I spent so long tweaking my granola recipe until it felt entirely mine.)

The main note I would give you is, if you’re trying to decide between Kwan and Friedl, and you’ve already acknowledged to yourself that it’s too close to tell with the naked eye, then you should put some weight—maybe the most weight—on which player you’re more likely to actually watch that day. Assuming you’re not in this to pay off your mortgage, the only real goal is entertainment—to make the game you’re watching more interesting and to increase your lived suspense. I’m not saying you should choose Friedl over Aaron Judge or anything, but if you’re starting with the premise that these dudes are basically interchangeable, choose the option that will entertain you! Choosing Friedl if you’re actually going to be watching Kwan is like trading dollars for manat. It doesn’t matter that you get a great exchange rate unless you’re actually going to Azerbaijan!

I wouldn’t want to talk you out of using any of your five factors. My own personal five-factor rubric would probably be:

1. Rough sense of player’s projections, or, put another way, which player is just better, as much as can be known.

2. Strength of player’s lineup/player’s spot in batting order (i.e. a player hitting third in a strong lineup strongly preferred over a player hitting seventh and/or in a very weak lineup, because I want that extra plate appearance and lots of runners on base).

3. Player’s past two weeks or so (despite knowing that streaks are usually illusory; I know this but I also love/hate a streak), particularly for young hitters and all but the very best pitchers.

4. Likelihood I’ll watch the game—what time it’s on, is it a game I’m otherwise interested in, am I rooting for one of the starting pitchers, etc.

5. Ballpark factor/opposing pitcher, only in extreme (top-five opposing pitcher, top-five park factor) circumstances.

3. ALEX ASKS!

[Regarding my Active-in-2016 Hall Of Famers Redraft article] Naturally I disagree with a handful of your picks (I'd have Longoria lower, Molina higher), but the one I think you're really off on is Jimmy Rollins.

I think most stat-inclined people expected Rollins to be one-and-done or close to it, but instead he debuted at nearly 10 percent and climbed each of the next two years. Voters, including some who use WAR, seem to be looking for reasons to support him, citing all sorts of intangibles to wave away his advanced stats.

I don't think he'll ever get to 75 percent on the BBWAA ballot, but I could see him cracking 30 percent, mostly from more old-school types, which will make him the exact kind of candidate the veterans committees like: A gritty character guy who anchored a memorable team, had some big seasons (an MVP award!) and drew enough support from the writers that he seems like a respectable choice.

I'd put his eventual HOF odds at 40-50 percent, at least!

SM: I think everything Alex said is correct. I’d also put Jimmy Rollins’ chances, in the long-tail HOF likelihood game, much higher than I initially had them. He’s just a very likable candidate, and in my large-hall mindset last year I considered voting for him. Winning an MVP Award really does something to my impressions of a player, hence my almost certainty of voting for Giancarlo Stanton and Andrew McCutchen someday, despite both seeming to land around 50, not the crucial 60, WAR. (Everything Alex says about me underestimating Rollins’ chances arguably applies, as well, to my estimates for Dustin Pedroia.)

The main reason I’m answering Alex here is to note that, when I wrote that piece, I estimated the HOF chances of 50 players who’d been active in 2016, and named 10 more who we might consider as > 0 percent. I didn’t name Matt Chapman at all. It took me about two weeks to realize that was a mistake.

Chapman, 31 years old, has 37 career WAR.

Christian Yelich: 42 WAR, 32 years old

Xander Bogaerts: 41 WAR, 31 years old

Alex Bregman: 39 WAR, 30 years old

Chapman: 37 WAR, 31 years old

Corey Seager: 36 WAR, 30 years old

Trea Turner: 35 WAR, 31 years old

Matt Olson: 31 WAR, 30 years old

I had Seager 40 percent likely to make the Hall, Turner 20 percent, Bregman and Yelich 15 percent, Olson 3 percent, Bogaerts as worth a mention. But Chapman is in the muddle with all those guys, and this year, the present day, the most current information we have of any of them, he’s been the best: Fourth in the National League (and ninth in the majors) in 2024 WAR.

There’s almost nothing harder to appreciate than a 4-WAR third baseman who doesn’t have a lot of home run power. Nine months ago, like everybody, I considered Chapman a free agent trap; some team would sign him to a multi-year deal and he’d just frustrate them in his decline years. Now, after watching him several times a week, I love him. You really have to see it every day to appreciate it: He runs extremely well for his profile, he hits the ball really hard, he makes small, smart decisions all the time. Look at this play:

If he stays back on the base to field that throw, it probably short-hops and he probably doesn’t get the out. So Chapman aggressively steps forward into the baserunner’s path to catch the throw on the fly. He keeps his feet way far apart to avoid blocking the base and violating the new obstruction rules. He catches as late as possible and drop-tags instantly, while also getting nutmegged by a baserunner. It’s a beautiful play; it doesn’t, incidentally, produce any WAR for him.

But most of what Chapman’s great at does produce WAR, a solid amount of it, and it is all adding up to a fringe-HOF career. He needs to age really well to get to 60 career WAR, and he might need to get to 65 or 70 (like Scott Rolen did) to overcome the stigma of being an offense-second corner infielder. But he’s definitely worth a mention.

4. JOHN ASKS!

Somewhere in my reading about the Pacific War in World War Two I came across the fact that the terms “on deck” and “in the hole” came from aircraft carriers in WW2. Sorry, but I have forgotten exactly where this factoid even came from. But, basically, the guy taking off would be on the starting line, the next plane would be on deck ready to be moved up and the second guy in line would be on the elevator in the hanger deck or “in the hole” created by the elevator being on a lower level of the ship. I have always wondered what terminology (if any) was used to describe this before the sailors came home from war and in the half century of professional baseball before, or if this is even true. I’ve tried to figure this out for a few years and haven’t figured out the correct way to go about it apparently.

SM: Fortunately the great lexicographer Paul Dickson traveled to Maine to solve this extremely niche puzzle, so I can put your mind at ease: While it's true that the origin is nautical—though "in the hole" is a corruption of the original, "in the hold”—the reason you can't find any terms that pre-date "on deck" and "in the hole" is that there were no previous terms. On deck and in the hole actually date back to the 1860s, and to New England fishing towns. Baseball Almanac has reprinted what Dickson wrote about it, so here you go: “Few borrowings are as evident as these words from a ship, where to be on deck is to be on the main deck (or floor) and the hold is the area of the ship below the main deck.”

If you really did see references to WWII aircraft carriers using “on deck” and “in the hole” to describe planes preparing to take off, I suspect it’s because the terms—having traveled from obscure fishing terms to mainstream baseball terms—traveled back to the nautical world, now in their slightly tweaked but very familiar baseball forms.

5. STEPHEN ASKS!

I know that, until I was 22 years old, I saw at least one Hall of Famer in every single MLB game that I attended. I'd guess that was about 60 games, from my first visit to a big league park until I was a college graduate accepting his first real job.

I know this because I can identify the five games I'd attended away from my childhood park up until that day (all had a Hall of Famer), and I discovered that my childhood team (the Orioles) had a 23-year stretch in which every single home game they played had at least one Hall of Famer. That streak begins on June 9, 1976 when Gaylord Perry takes the mound and ends with Harold Baines sitting out a game on August 8, 1999. It, of course, rides along on back of Cal Ripken's streak, but it also depends largely on Eddie Murray for 5+ years and on Reggie Jackson for most of its first fraction of a year. For one crucial game in each instance, it is saved by (visiting players) Jim Palmer, George Brett and the triumvirate of Yaz, Rice and Tony Perez. And as it sputters toward its end, Harold Baines keeps it alive a few times.

SM: Crazy thing: The first game I ever saw without a Hall of Famer was also my first game... or so it seemed, for the longest time. But I just glanced at the box score and would you believe it, there's Ted Simmons, pinch-hitting for Billy Sample in the seventh inning and drawing an intentional walk. My first brush with fame! Simmons was 36 at the time—done as a major league regular—and it took him another 36 years to get inducted, including getting just 4 percent in his one-and-done appearance on the writers’ ballot. So what I'm saying is, it takes a really, really, really, really long time to rule a game conclusively free of a HOFer.

6. B. LAMONTZ ASKS!

I’m still waiting for someone to investigate why with a full count, two outs, runners going to be in motion, I have not, in nearly 40 years of baseball, ever seen a pick-off attempt at third, when the runner almost certainly would be a sitting duck.

SM: I once had a long argument about basically this question, with the Sonoma Stompers’ brilliant catcher Andrew Parker. We were sitting in the bullpen at San Rafael—lawn chairs about 25 feet from third base. There was a runner on third, who the defense was ignoring as always. (He wasn’t going to steal home.) The runner was taking a pretty large lead, maybe 20 feet. He looked complacent, knowing he was in no danger, totally out of the defense’s mind, and the third baseman probably 25 feet away from the base himself. I argued that, if the third baseman suddenly broke hard for third, and the pitcher threw over, and the throw and the third baseman got to the base at about the same time, the runner would never get back in time. I understood that the runner’s lead didn’t really matter—hence not holding him on—but the out mattered, the out would have ended the inning. So why not hunt the out?

Parker’s answer, which I made him repeat 20 times in this drawn-out argument, was simple: Ballplayers aren’t very good at ball. He said the pitcher would throw the ball away, the third baseman would muff it trying to catch it, somehow they’d screw up and the runner would score. If it’s not a play that they have experience with—lots of game experience—they wouldn’t get it right.

Fine, I guess. But I’d like to see more ambush/timing plays to get surprise outs when the defense is thought to be indifferent. When the bases are loaded, and nobody is holding the runner at first on—well, that’s a great time to backpick him, he’d never expect it! I understand why they don’t try—that runner generally isn’t worth holding on, and it’s generally preferable for the first baseman to be in the best position to field a batted ball—but I think it’d be an easy out once.

I’d like to see a team, just once, actually contest it when a meaningless runner takes second base on defensive indifference in the ninth inning. Just once, surprise the runner, throw down! Maybe the run doesn’t matter, but the out does. Hunt outs.

Anyway, despite Andrew Parker’s patience and persistence with me, I remain with B. Lamontz: Timing play pickoff attempt at third base with two outs and a full count and the bases loaded. Do it. The moment that is the most predictable is the best time to surprise somebody.

7. JODY ASKS!

Given our ability to now quickly measure virtually anything on a ball field, I could see us in a year or two having immediate on-screen judgements/measurements of a runner’s jump.

How cool would that be to immediately assess credit/blame and know it was accurate instead of broadcaster guessing?

At this point we can measure the runner’s speed as well as the speed of the throw, speed of the pitch, quickness to home plate and catcher’s pop time. I’d like to see a “report card” after a stolen base (or caught stealing) that showed each of those numbers on-screen with an indicator as to which numbers were above/below average. To me, that would be amazing.

Yes, while I’ve really been giddily deploying my personal Is The Jump Good standard, a good jump metric seems like it would be outrageously simple for Statcast, and I’d be surprised if they don’t release one in the next… three or so years. The ideal jump metric would be this simple:

How many feet from first base is the baserunner when the pitch is… say, 50 feet from home plate. That would cover every aspect of the jump that my own standard does, plus it would include the size of the baserunner’s lead, which would be an upgrade on mine. (Making up numbers:) 24 feet good jump, 21 feet okay jump, 18 feet bad jump, something like that.

Statcast tracks, or at least used to track, baserunner leads, so I’m confident this is realistic.

8. JOSH ASKS!

What does it actually mean for a pitcher to "give in"? Broadcasters are obsessed with the idea that a good pitcher never does so. "He's not going to give in here, count on another tough pitch." What I think they imagine is a scenario where an exhausted, mentally defeated pitcher simply stops competing, and lobs it over the plate like a softball, as a form of pitching seppuku? Is there a more subtle way pitchers actually do give in? How would we tell?

SM: By “count on another tough pitch,” they're not contrasting that with “oh, he's going to just melt down and suck now.” Rather, they mean he's not going to prioritize throwing a strike above all other considerations. This used to mean “he's not necessarily going to give in and throw a fastball just because it’s a fastball count.” But now there's no such thing as a fastball count. So, he’s not going to give in now means the pitcher isn’t going to to aim for the heart of the strike zone just because he’s behind in the count. It means that he’ll still aim for a corner, and if he misses his spot and walks the batter, then he misses his spot and walks the batter, and moves on to the next batter. He's not going to “give in” and let the best hitter in the lineup do multi-base damage.

Related to this, I recently heard something that really stuck with me. A batter had swung at a 3-2 off-speed pitch that wasn't in the strike zone. It might even have been with the bases loaded. He'd gone back to the dugout and told a teammate, “I thought he'd be afraid to walk me.” His teammate said, "they're never afraid to walk you. They're afraid to give up a hit." More and more and more and more that explains what I see in three-ball counts, where pitchers refuse to “give in.” We think they're afraid of the walk. At some psychological level, they're not.

Baseball Reference WAR, in all mentions.

I am in a fantasy league with reader Everett and it pains me to admit that whatever his several hundred word, 5-category ranking system is, it appears to be working. After middling results for his first 8 years in the league, he's gone 1st, 2nd, 2nd, 1st, 2nd (lost in a tie-breaker), and what is sure to be 1st again this year. (sad face)

Re: the timing pickoff to 3B.

Bases loaded, full count is the exact time *not* to try this.

1) Most pitchers pitch out of the windup not the stretch with bases loaded so runners are safe to take off on first move.

2) When the pitcher is throwing out of the stretch, most sensible runners won't start from 3rd in that situation until it's clear the pitcher is going home.

3) If a runner gets complacent and does go first-move when the pitcher is throwing out of the stretch and the pitcher tries an inside move to throw to a moving target 3B going to cover the bag, the runner wouldn't hit the brakes and head back to 3rd, he'd just keep going and score.

This move (sneak pick of runner on 3rd) would work best with runners on 1st and 3rd (pitcher is working out of the stretch) and in that situation, I bet a team could steal an out in a key situation. The challenge would be to signal to the third baseman that a throw is coming.